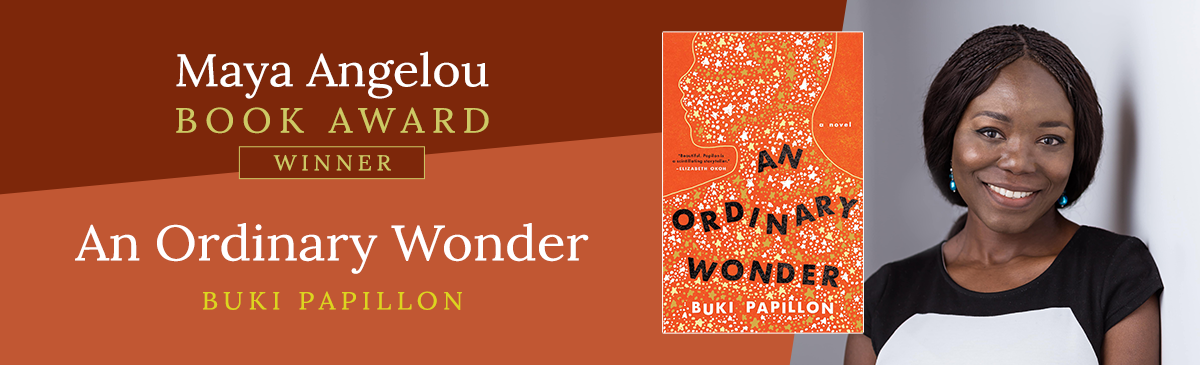

Story of a scorned child is indeed ‘An Ordinary Wonder,’ our book club readers find

Buki Papillon's award-winning debut novel, An Ordinary Wonder, is told through tense divisions — starting within the protagonist’s body.

Otolorin is physically both male and female, intersex. Otolorin is a boy and a girl, raised as a boy while knowing she’s a girl. Otolorin is a twin.

Nine readers from across the metro recently gathered for a meeting of the FYI Book Club at the Kansas City Center for Inclusion in Westport to make sense of this character and their dueling dual existences. The author joined the meeting via Zoom toward the end.

An Ordinary Wonder won the 2022 Maya Angelou Book Award, the first time it’s been given for fiction. But the characters and their thoughts are imagined with such depth, that the novel almost reads like nonfiction, said Judith Reagan, of Brookside. “Most fiction you read, and you know it’s fiction,” she said. “But this, I had a hard time separating the two.”

And maybe that feeling is largely due to the early and insistent acknowledgment that no one is just one way. Not only is Otolorin male, female, boy, girl and a twin, but Papillon writes equally complex family and friend responses to this multidimensional character.

Leading the discussion, Kaite Stover, the Kansas City Public Library’s director of readers’ services, noted that the book alternates sections in the past and present.

We see Otolorin from age 12 in 1989 through age 16 in 1993. All but the final chapter and epilogue is set in the author’s native Nigeria.

"Oto is struggling with figuring out who they are in the 'before' section," Stover said. "In the 'now' section, when Oto is at school, the fear is more, 'I understand who I am, I’m still confused by who I am. But now I am fearful of how others are going to react to who I am.'"

Tori Kottwitz, from Westwood Park, said she found the structure challenging and had a slightly different take on its significance. In the "now," Otolorin understands that no one will be a champion for them as they work to claim a female identity in a society where even discussing that struggle is taboo.

"Instead of feeling at the mercy of his mother and all the adults who let him down, I just thought that in the 'now' section I saw glimmers of he’s beginning to take charge, you know, to make his way in the world because he didn’t have anyone else that was going to do it for him," Kottwitz said.

For Otolorin, taking charge means leaving the home they’ve shared with their mother and twin sister after independently gaining admittance to a boarding school — the only solution for not only escaping a bad situation at home, but for establishing their true identity.

The mother views Otolorin as a monster and never hesitates to say so. Otolorin’s father abandoned the family at the twins’ birth, repulsed and frightened by Otolorin.

The maternal and paternal grandmothers push and pull on the family in selfish ways that also threaten the two children, Otolorin in particular.

"The thought of a child not having a significant adult to make the child feel loved was extremely disturbing," says Lisa Timmons of Overland Park. "My hope was that all it’s going to take is one person to know that you are an 'ordinary wonder,' you are who you are."

And that is what Otolorin finds at school, though not immediately. They meet Mr. Dickson, a teacher with his own history of trauma stemming from his early expression of his sexual orientation. The teacher aims to protect his student.

But in a society as deeply rooted in superstition, tradition, and a good deal of closed-mindedness, such a move takes guts.

Timmons recalls an interviewer commenting that Papillon, as a Nigerian, was brave to write this book. Papillon, who writes and even seems to speak in proverbs, responded that a turtle doesn’t move forward without sticking out its neck.

Papillon addressed this bravery when she joined the book club meeting from her home in Massachusetts. She said Mr. Dickson is the character she identifies with most.

"No matter what it costs him, he’ll stick his neck out to help this young girl that has been raised as a boy," Papillon said. "I feel like writing this book has come out of a lot of the circumstances that I saw as a child that I felt that I couldn’t do anything about because I was too little."

Papillon told the group about growing up the oldest in a family of six and how a person’s first understanding of the way the world works is based on family dynamics.

In An Ordinary Wonder the family dynamic keeps Otolorin’s identity split. Even Wura, the twin sister, unwittingly has a hand in holding open the unsettling schism.

"As children," Papillon said to the group, "we’re always trying to do whatever we can to keep the peace because we don’t have the power to do anything any other way. So, Wura is stuck in this place where she thinks, 'Oh Oto, if you will only just be who everyone is saying you are.' And Oto says, 'Well, I can’t because that’s not who I am.'"

So, it doesn’t feel ironic that what finally mends Otolorin — and the entire family — is the character’s ferocious commitment to independence, to breaking away entirely.

Timmons cited a passage toward the end of the novel. "'It occurs to me to change my name to Lazarus, not Lori, because I truly feel like I am back from the dead,'" she quoted. "The power in a name and the power in your identity and the power of being who you are."

Author Presentation

Buki Papillon will speak at 6 p.m. on Wednesday, April 12, at the Plaza Branch of the Kansas City Public Library, 4801 Main St. The event will be livestreamed and also available to watch online later at youtube.com/kclibrary .

Details »

Watch Video

Join the club

The Kansas City Star and the Kansas City Public Library present a book-of-the-moment selection every few weeks and invite the community to read along. To participate in the next discussion led by Kaite Stover, the library’s director of readers’ services, email kaitestover@kclibrary.org.