Meet the humble Kansas City woman who wrote WWII poem ‘heard ’round the world’

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Joanna Marsh | lhistory@kclibrary.org

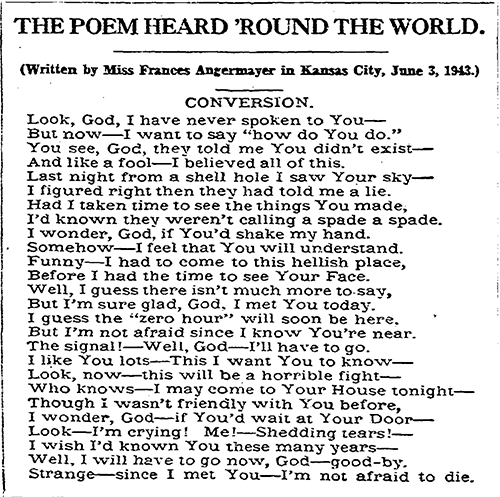

It was a hot June night in 1943, and Frances Angermayer could not sleep. So, she arose after midnight, went to her typewriter, and—in twenty minutes—wrote what was to become the most famous poem of World War II.

This week’s “What’s Your KC Q?” explores the astonishing story of “Conversion,” a verse about a soldier’s talk with God that brought hope to millions of readers during the height of the war. The poet, an unassuming secretary from Kansas City, could not have foreseen that her simple composition would find its way into the hands and hearts of countless soldiers across the globe.

Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library

Before Frances Angermayer wrote “the poem heard ’round the world,” she led a quiet life. Born in 1907, she was a lifelong resident of Kansas City and a devout parishioner of Our Lady of Sorrows Catholic Church, where she also attended parochial school. Later, she became a secretary at the office of pediatrician Dr. Joseph B. Cowherd, a position she held until retirement.

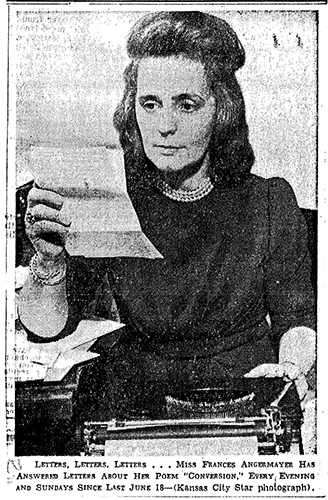

Angermayer’s poetry, which she wrote in her spare time, evoked a playful, pious, and empathetic spirit. People often called her humble and modest. Even after Angermayer became a local celebrity, Kansas City Star writer Margaret Hamilton described her as “extremely shy” and “terrified” to speak in public, though she appeared to be successful at it.

After all, she obliged repeated requests for interviews about her famous poem, spoke at local assemblies, and expressed her convictions publicly. In 1956 she wrote a passionate letter to the editor of The Star denouncing the racist mob that harassed Autherine Lucy for challenging the whites-only policy for students at the University of Alabama.

“Tell me,” Angermayer wrote. “When our country is at war, are people of another race barred from fighting and dying for our country?”

It is not surprising that Angermayer used war to illustrate her point, for she knew it well. She was 36 years old in 1943 when, during the throes of the Second World War, she experienced the restless June night that inspired “Conversion.” Troubled by news from the front, she lay awake praying for her stepbrother, Glenn Virtue, an Army corporal stationed in the South Pacific. Her thoughts drifted to others on the battlefield.

“I wondered what a soldier facing death would do,” Angermayer later wrote. “How would he feel if he had no religious training, if he did not know God? I placed myself in such a situation, and the words of ‘Conversion’ came to me.”

She finally arose after midnight and got to work on her typewriter, careful not to wake her parents, with whom she lived at 2548 Gillham Road. Within 20 minutes, she had written the first version of the poem, originally titled “A Soldier’s Conversion.” Two more drafts yielded minor changes, including the shortened title. The entire process took less than an hour.

The poem itself was plainspoken and earnest, qualities that would contribute to its popularity. As Angermayer’s pastor, Father J. F. McGee, put it: “The appeal in the lines is in their simplicity; big truths told in the simplest language that the plain man and woman understands and loves.”

Having published previous poems, Angermayer sent “Conversion” to Our Sunday Visitor, a Catholic publication based in Indiana. Women’s editor Mary E. McGill published the poem on July 18, 1943. Angermayer didn’t hear much about it until a year later, when “Conversion” was broadcast to servicemen on a Des Moines radio show—the first in a series of events that would lead to the poem’s phenomenal popularity.

After the broadcast, a column in The Atlanta Constitution reported that an unattributed poem was found on the body of a U.S. soldier in Italy. While traveling, the Rev. Edward J. Morgan of Kansas City’s Centropolis Baptist Church clipped the poem from the paper and then used it in a sermon back home. Morgan received repeated requests for copies and eventually broadcast it over radio station WHB, still uncredited. Some of Angermayer’s friends recognized the poem and set about informing the public of its authorship, a task that would be repeated often.

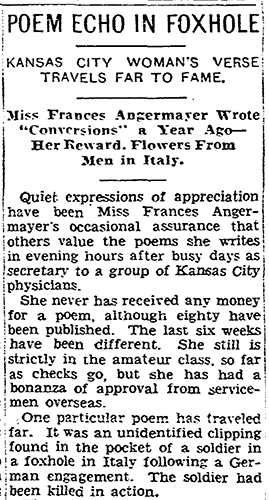

Word spread quickly, for Angermayer soon received flowers and a note of appreciation from a camp of soldiers in Italy. This story was reported in The Kansas City Star in June 1944 with the headline “Poem Echo in Foxhole.” The reserved poet could not imagine the flood of correspondence that was to follow, or just how far her work had already traveled.

By December 1944, “Conversion” had been cited in The New York Times and read in Congress by a U.S. representative. A New York Daily Mirror columnist called it “the outstanding poem of this war,” and newspapers across the country continued printing it, sometimes under different titles. The piece was translated into several languages and, by spring of 1945, an estimated 6 million copies had been sent to soldiers in nearly every theater of war.

Angermayer, who never earned money from her poetry, found herself covering the cost of printing and postage as requests for copies poured in. Local printers began to help by sending her copies free of charge, and some organizations published large quantities independently. Following the poem’s appearance in the Hebrew Chronicle, 250,000 copies were donated to Jewish soldiers. St. Francis of Assisi Church in New York also published 75,000 unattributed copies before learning of the author and reprinting 100,000 with the correct credit.

Her friends’ efforts to cite Angermayer as the author continued, as more copies were attributed to the fallen soldiers who carried them. “Conversion” was also increasingly recited, often uncredited, on the radio. Celebrities including singer Ginny Simms and actors Joe E. Brown and Shirley Temple read it on major broadcasts. Once Temple learned that Angermayer was the author, she insisted on doing a second reading, gave Angermayer due credit, and sent her a signed photograph. In 1945, a fan reported that an unnamed African American actress gave a beautiful reading of “Conversion” on KMBC in New York. The actress stated that the poem was found on a black soldier in Belgium.

“Conversion” was also set to music and recorded by singing cowboy Denver Darling in the fall of 1945. The Kansas City Star reported: “The ‘foxhole’ poem by Frances Angermayer, with music by John W. Bratton and Geoffrey O’Hara, is sung in the best western style with a beat suitable for dancing.”

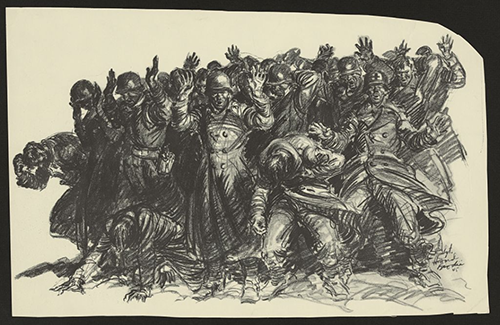

As her poem grew in popularity, Angermayer received hundreds of phone calls and letters of gratitude from servicemen overseas. Copies of “Conversion” were found on the bodies and among the personal effects of soldiers in North Africa, China, the South Pacific, the Aleutian Islands, and throughout Europe. Sometimes, entire battalions carried it with them into battle, and Angermayer’s brother watched with wonder as his sister’s poem was distributed to troops in the Solomon Islands.

Some tales of the poem’s presence on the battlefield were particularly poignant. On D-Day, June 6, 1944, numerous copies were found scattered about the beaches of Normandy. A Catholic chaplain recalled crawling among the wounded and dead, some still clutching the poem in their hands, while many copies drifted through the wind.

To Angermayer’s astonishment, she heard a report that her poem had somehow been smuggled into the Buchenwald concentration camp and secretly passed among some of the prisoners. After the Battle of Metz in northeastern France in 1944, U.S. Army Capt. Roland L. Lanser of Kansas City found a German translation on the body of a dead Nazi soldier. Lanser was unaware that the poet hailed from his hometown.

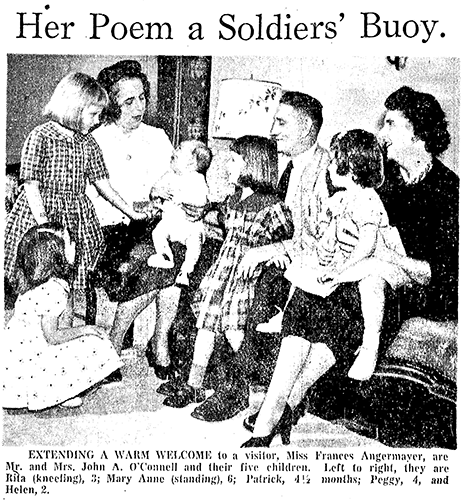

It was not the only time “Conversion” would find its way into the hands of a local serviceman overseas. Army Cpl. John A. O’Connell, a 23-year-old from Kansas City, Kansas, credited Angermayer for his survival of the Malmedy Massacre during the Battle of the Bulge. On December 17, 1944, Germans attacked O’Connell’s convoy and captured him along with over 100 other U.S. soldiers. Rather than sending the prisoners to camps, the Germans lined them up and opened machine gun fire. Afterward, they walked among the wounded Americans, brutally killing survivors.

O’Connell, who had already memorized “Conversion,” repeated it to himself as he lay with bullet wounds to his face, hand, back, and shoulder. He prayed for the strength to keep still while the Germans lingered nearby for six hours. Miraculously, they left him alone.

He and a few other survivors managed to make their way back to the American front and were taken to a hospital in Paris. O’Connell immediately wrote to Angermayer to explain how her poem helped him survive. His letter was one of many that brought her to tears.

“Even now,” Angermayer told The Star in 1957. “It is impossible for me to believe I wrote a poem that meant so much to so many.”

Indeed, newspaper reports of the poem’s influence on its readers were so numerous that Angermayer’s relative obscurity is somewhat baffling, though perhaps befitting her humble nature. She died on July 25, 1993 at age 86, her obituary containing only a brief mention of her remarkable poem.

The words of Lt. Harry C. Slawson of the Army’s 102nd Signal Corps may provide a better tribute to Angermayer’s legacy: “I myself, the men under me and men far removed have known literal moments of ‘hell’ and the presence of God that you shared with us… I came across your poem just today. By tonight it had found its way to every man within the company—and left its mark. Men have died near me, men will die in the future, perhaps myself—but I know this, the thought you have left with us will last beyond whatever may come in the future.”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.