New KCHistory Collection - KC Organized Crime Files

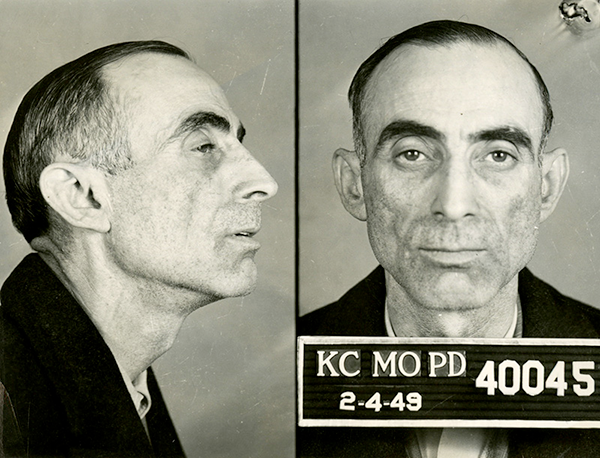

We are pleased to announce the addition of our Organized Crime Files collection to KCHistory.org. Compiled by The Kansas City Star from the 1930s through the 1970s, the files were used by reporters covering the crime beat. Each file is filled with police mug shots, photographs, reports, memoranda, and notes detailing the mafia-like activities of the so-called Kansas City Outfit. Reporter Mike McGraw discovered the collection at the Star offices and donated it to Missouri Valley Special Collections in 2017. The contents of the collection, in their entirety, have now been scanned and made available to the public.

The North End

As early as the 1880s, Kansas City was receiving an influx of Italian immigrants. Attracted by the opportunity to work in the booming railroad and meat packing industries, the newly arrived Americans settled in a close-knit community just east of today’s River Market. Roughly bounded by Grand Avenue on the west, Highland Avenue to the east and Admiral Boulevard to the south, life in Kansas City’s North End, or “Little Italy,” mirrored that which its new occupants had left behind in the old country. While many of the early settlers had come from regions on the Italy’s mainland, those arriving after about 1900 were overwhelmingly from Sicily. They shared a linguistic and cultural heritage, lived next door to one another and supported local businesses, so learning English and fully adopting the American way of life just did not seem like a high priority.

The Black Hand

Language and tradition were not all that came over from Italy. Resulting from generations living under foreign rule and a feudal economy, a mistrust of authority, self-reliance and family loyalty had become defining characteristics of the Sicilian mindset by the early 20th century. Of course, that is not to say all who made the trip to America were criminals. Like many other immigrant communities, the residents of Little Italy were hardworking and ambitious people who had risked everything for the chance at a better life. However, numerous police crackdowns in Italy over the years forced many criminals to join their countrymen and flee across the sea. Just as honest citizens were opening bakeries, butcher shops, grocery stores or finding work elsewhere in the city, those with more sinister aspirations setup extortion and blackmail rackets in the new neighborhood. Threatening letters warning of the consequences of not paying up and bearing menacing drawings of pierced hearts and stilettos became the calling card of the new “Black Hand,” the nickname given to gangs popping up in the North End.

Prohibition and Professionalism

Big changes came to the Black Hand when national prohibition took effect in 1920. Whereas exploitation of the local, Italian community had been their primary focus, the earning potential of illegal liquor production and trafficking both expanded and professionalized their criminal endeavors. Black Hand brothers Joseph (Joe Scarface) and Pietro (Sugarhouse Pete) DiGiovanni laid the foundation for the Kansas City Crime Family in the 1920s. In the wake of the Volstead Act, the duo immediately started up production.

Despite getting in early on the action, the DiGiovannis had their competitors. To consolidate control over bootlegging in the area, the brothers setup the “Sugar House Syndicate.” Through cooperation with five other gangs, the group dominated the sugar supply, a necessary ingredient for alcohol fermentation. They controlled the price and supplied sugar to smaller outfits, taking a portion of their product in return. By 1933 when prohibition was repealed, the major players in the illicit booze trade had made themselves rich.

Wide Open Town

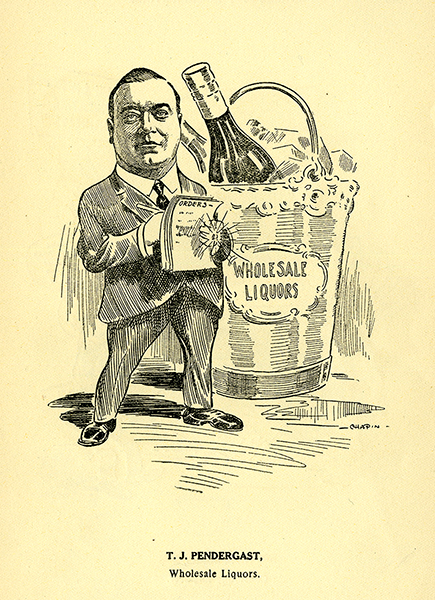

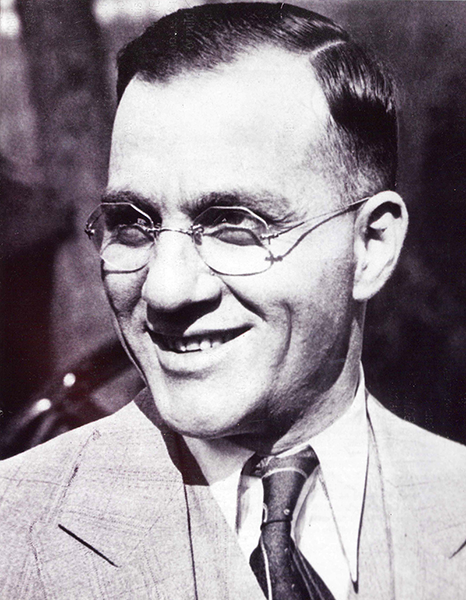

Kansas City was gaining a reputation as a “wide-open town,” where all manner of vice could be indulged, and the booze flowed freely. Brothers Jim and Tom Pendergast came to Kansas City from St. Joseph in the late-19th century. First entering the saloon trade, the brothers soon demonstrated a knack for political organization. When Jim died in 1911, younger brother Tom assumed control of the growing Pendergast Machine, the political organization that exerted control over local government until its collapse in 1940. Boss Tom controlled working class, Democrat votes and thereby could bend elections to his will. Initially establishing himself in the pre-prohibition wholesale liquor trade, he eventually transitioned to an industry that could directly benefit from the government building contracts he controlled – ready-mix concrete. But Boss Tom never forgot his ties to the saloon and liquor businesses. Kansas City lived up to its “Paris of the Plains” nickname as a direct result of Pendergast’s control over the police department and lax enforcement of prohibition laws.

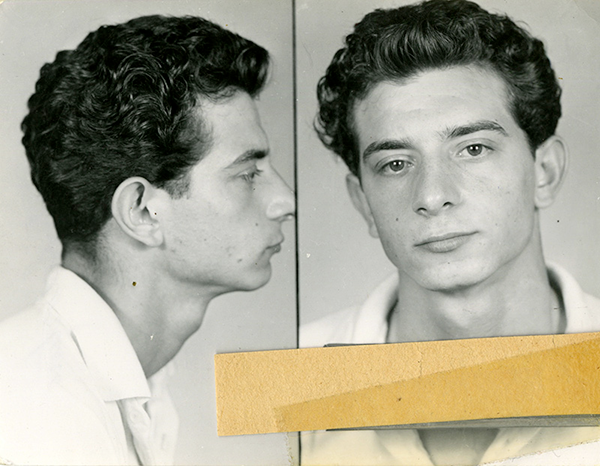

John Lazia

It was in the Sugar House Syndicate years that a gangster from Brooklyn wrestled control of the Northside Democratic Club away from a Pendergast lacky. Rather than retaliating, Boss Tom struck a deal with John Lazia: turn out the vote for the Democratic ticket, keep the violence to a minimum and the police will look the other way. Lazia became so integral to the machine politics that he secured police jobs and appointments for a few of his criminal friends once Pendergast wrestled control of the police away from the state in 1932. On paper, Lazia was a businessman, the owner and operator of the Glendale Bottling Company and the posh nightclub Cuban Gardens, but his real trade was managing the DiGiovanni’s criminal operations.

Lazia’s sway over crime in the city was so complete that he factored into the story of two notable kidnappings: that of fashion designer Nell Donnelly Reed and the daughter of City Manager Henry McElroy. In 1931, when Nelly Don’s husband, U.S. Senator and Pendergast-ally James A. Reed, learned of his wife’s abduction, Lazia was called upon to fix the situation. His men quickly learned where the kidnappers were holed up and ended her captivity, one of the armed men reportedly apologizing for the inconvenience: “Mrs. Donnelly, there has been a mistake. These men are from out of town. You have a lot of friends. We have come to rescue you.” The following year, when Mary McElroy was abducted from the family home, Lazia is suspected of providing the ransom money paid to the kidnappers.

With Pendergast Machine support, Lazia’s reign over organized crime went relatively smoothly. However, an event in 1933 put the Kansas City underworld in the national spotlight.

Oklahoma bank robber Frank Nash escaped from Leavenworth Penitentiary in 1930. The career criminal first escaped to Chicago, but eventually surfaced in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Federal Bureau of Investigation agents and Oklahoma law enforcement officials caught wind of Nash’s whereabouts and arrested him at a cigar store on June 16, 1933. The group loaded their prisoner on a train bound for Kansas City, planning to complete the trip back to Leavenworth by car from there.

Unfortunately, word of Nash’s capture and the train’s arrival time leaked to his friends. Allegedly, gangsters Vernon Miller, Charles Arthur (Pretty Boy) Floyd and Adam Richetti hatched a scheme to meet the group with machine guns outside of Union Station and demand Nash’s release. Miller went so far as to obtain permission for the holdup from Lazia, the pair meeting at the Fred Harvey restaurant inside the station the day prior.

Things did not go according to plan. Gunfire from both sides erupted. When the shooting was over, four law enforcement officers and Nash himself lay dead at the scene and the gang had escaped. With one of the victims being an FBI agent, a nationwide manhunt followed. Miller, Floyd and Richetti all eventually met untimely ends after that fateful day in June, but many mysteries related to who was and was not involved and to the crime’s actual motivations persist to this day. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover used the event to expand the powers of his agency and turn its attention toward cracking down on organized crime in the U.S.

Ultimately, it would not be the FBI that would remove Lazia from power. In the early morning hours of July 10, 1934, Lazia and wife were entering their apartment at 300 E. Armour Boulevard when two gunmen emerged from hiding and opened fire. Their driver managed to save his wife, but Lazia was struck eight times. He was rushed to St. Joseph’s Hospital, but died later that afternoon. While no one was officially charged with the Lazia murder, it is widely believed that his attackers were two low-level KC mob up and comers hoping to make a name for themselves, or perhaps ordered to make the hit by Lazia’s driver, Charles Carrollo, who took control of the Kansas City Syndicate after the hit.

Growing the Outfit

With the end of national prohibition and the eventual fall of the Pendergast Machine, the Kansas City Crime Family had to diversify. After Carrollo was sentenced to prison in 1939, Charles Binaggio assumed power. Quiet and unassuming, Binaggio’s nature masked his ambitions. With control of the police department reverting to the state in the wake of the Pendergast cleanup, the new boss wanted his hands on the strings of power in Jefferson City rather than merely on those at City Hall. With the backing of crime families in other cities, Binaggio enacted a plan to steal the 1948 Missouri Governor race. The prize? Legalized gambling in Kansas City and St. Louis. At first, things were going as planned. Forrest Smith, Binaggio’s handpicked candidate won the vote. However, once elected, Smith proved unwilling to fully cooperate with the scheme. Ultimately, Binaggio was unable to secure control of the Governor’s office and state police board as promised. Reassurances to investors were made, but Binaggio along with associate Charles Gargotta were assassinated in his office on April 5, 1950.

The River Quay War and Beyond

Unlike his predecessors, new organized crime king Nick Civella, was born and raised in Kansas City’s Little Italy. His coronation occurred in November 1957 at the infamous Apalachin crime summit, where Civella was formally made head of the Kansas City Outfit by the assembled national mafia heads. His reign was characterized by cold calculation, little tolerance for challenges to authority and a desire to keep a low profile.

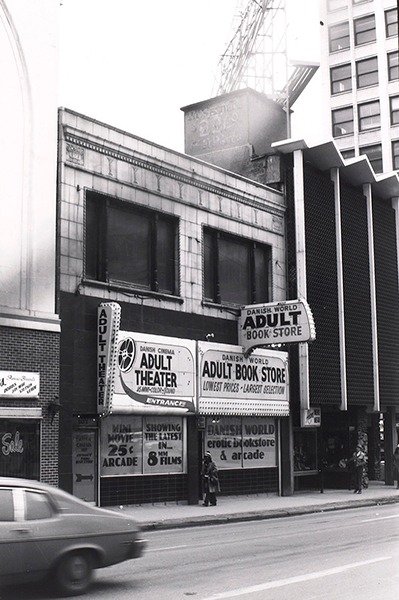

Civella’s wish to stay out of the spotlight vanished in the 1970s. To erase vestiges of Pendergast’s wide open town legacy from the planned Civic and Convention centers along 12th Street, city leaders closed the adult entertainment venues and dive bars that crowded the strip. Many of the evicted businesses were mob-associated and their operators began looking for new accommodations.

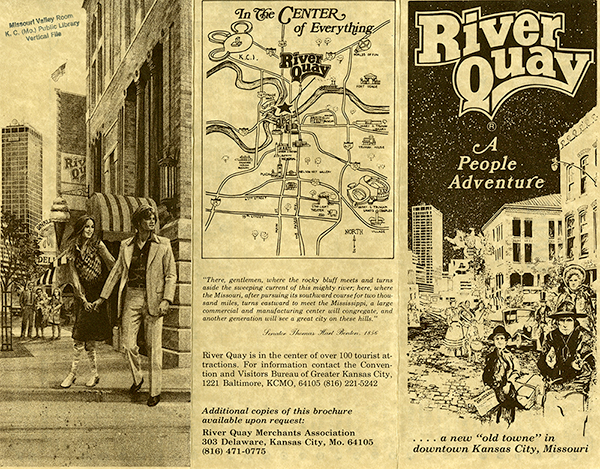

Just as the mob-run joints on 12th were getting the boot, an urban revitalization project in the old River Market area was getting underway. In 1972, economist and entrepreneur Marion Trozzolo began buying up old and forgotten buildings in the River Market, planning to refashion the neighborhood as an arts and entertainment district. Trozollo’s River Quay was an instant success, and Kansas Citians began returning to the oldest sector of the city to visit its eclectic shops, restaurants and nightclubs.

Unfortunately, the success was short-lived. The mobsters set up shop, and soon the character of the neighborhood changed from hippy-chic to red-light district. Honest businesses were muscled out, and by 1977, very few remained. The scramble to take advantage of River Quay led to friction in the organized crime ranks leading to a prolonged war as entrenched mobsters and lackies vied for control of the new turf. Civella’s low profile was about to end.

Uncle Joe’s Tavern, a bar owned by mobster brothers William (Willie the Rat) and Joe Cammisano, was hit by arsonists in September 1976. Afterwards, the tortured mutilated body of one of the suspects was found in the trunk of a car parked at Kansas City International Airport. This eye for an eye cycle of violence continued until March of 1977 when tactics escalated. Taverns Pat O’Brien’s and Judge Roy Bean’s near 4th and Wyandotte were both bombed and reduced to rubble. The once vibrant revitalization project was now seen by Kansas Citians as ground zero in a mafia turf war.

The very public River Quay feud attracted the attention of federal authorities. In 1978, the FBI bugged one of Civella’s hangouts, the Villa Capri Pizzeria at 2609 Independence Avenue. Hoping to connect Civella’s men to the River Quay violence, investigators instead learned of an elaborate skimming operation involving Las Vegas Casinos and the Teamsters union. Strawman, as the investigation came to be known, led to the downfall of Civella, who was caught on tape personally directing the scheme.

While Kansas City is not known as a hotbed of organized criminal activity like it once was, a line between then and now does exist. In the aftermath of the Strawman investigation, control over the Kansas City Crime Family has been handed down through the Civella clan. In 2006, John Joseph Sciortino, godson of Nick Civella’s nephew, was reportedly made head of the Kansas City Outfit.

Information about these stories and many more can be found in the new Organized Crime Files collection.