Unwed Black mothers in 20th century Kansas City found refuge in home for women, girls

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Anna Spoerre | aspoerre@kcstar.com

Unwed, expectant mothers as young as 12 years old, faced with societal scorn and the subsequent trauma, had few options in mid-20th century Kansas City.

Even more limited were the resources for Black women and girls. Many white mothers chose, or were sent, to deliver their babies and give them up for adoption in special facilities for unwed mothers. But many of these homes — with hundreds cropping up across the country — were segregated.

When Barbara Haar worked as a therapist and social worker at the Florence Home for Colored Girls in the late ’60s and early ‘70s, she would tell the residents — who ranged in age from 12 to 35 — that they had nothing to be ashamed of.

Haar’s work, the product of a vision launched in 1925, gave expectant Black mothers who were unwed the opportunity to find shelter and support in Kansas City.

In 1965, just years before Haar began work at the home, 24% of Black infants were born to single mothers compared to 3.1% of white infants born to single mothers, according to The Brookings Institute.

An inquiry prompted by “What’s your KCQ?” reporting on the Willows Maternity Sanitarium, led the community engagement partnership with the Kansas City Public Library to dive into the history of Florence Home — and how it served Black Kansas City mothers who were neglected elsewhere.

In the early to mid 1900s, multiple homes for expectant mothers popped up around the metro area as parents and partners turned a blind eye to the unwed mothers. Many pressured them to give up their children, Haar said. Some even had mothers sign relinquishment papers before the babies were born.

But during therapy at Florence Home, they spoke about life beyond pregnancy and discussed adoption as an option rather than a necessity, said Haar, who began working at the home in 1969.

“So many of them came so fearful, fearful of the whole physical aspect of having a child and then fearful of the emotional aspect of giving up a child,” Haar, now 78, said in a recent interview with The Star. “And we gave them ample opportunity to talk that through because it was our concern that they never felt forced to give up their child.”

While white, unwed, expectant mothers had a few places in the Kansas City area to turn for support depending on their income, including the Florence Crittenton Home, these locations denied care to Black mothers.

Elizabeth Bruce Crogman took notice. As a volunteer with the Urban League and Jackson County’s juvenile court, Crogman met many single Black mothers who lacked shelter, food and access to adequate medical care before and after pregnancy.

“I used to go to the juvenile court, and I would feel sorry for these girls because they didn’t have any place to go, and they didn’t have any place to leave their babies because their parents didn’t want them and they couldn’t go to the white Crittenton home, so I felt I had to do something,” Crogman, a Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, native, said in the book, “Kansas City Women of Independent Minds,” by Jane Fifield Flynn.

So in 1925, Crogman opened the Florence Home for Colored Girls at 2446 Michigan Street, thanks to help from the well-known philanthropist William Volker.

What began with about four bedrooms housing several unwed Black mothers and their children later turned into a much larger operation.

When the home outgrew its space, Volker donated $10,000 to expand, and Mrs. William N. Marty donated land at 24th and Campbell Avenue near Hospital Hill. A new four-story, colonial-style home was opened in 1930 at 2228 Campbell Avenue.

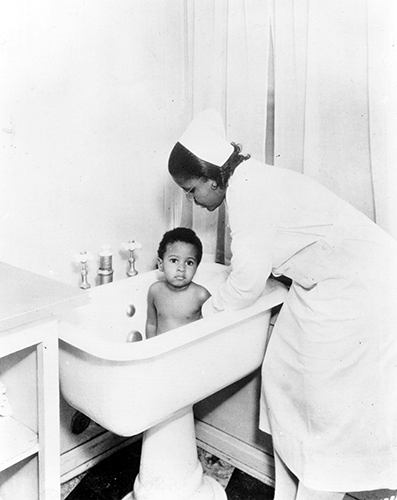

Community members, including physicians and nurses, volunteered in the hospital and nursery. Classes were also offered, including in sewing, cooking, housekeeping and Bible study.

By the 1940s, the home also began offering counseling, education, shelter and medical care for up to 30 mothers and their children. Some residents paid their own way, but a government welfare service paid the way for mothers who couldn’t afford it, Haar said.

It was important to the staff that the girls felt accepted and treated with respect, rather than blamed or shamed for their pregnancies, Haar said.

Some stories were heartbreaking. A few of the expectant mothers had been raped by their fathers, Haar said.

“But I think the fact that we were able to offer them therapeutic services was very helpful,” Haar said. “And of course we helped them take their fathers to court.“

She made it clear to all the mothers that even if they left, they could always come back to talk. And some did.

“I think that society kind of closed the door on pregnant teens,” Haar said. “And I think still young women get blamed more than the fathers do.”

Haar never worked for Crogman, who directed the home until her retirement in 1945; while there, she provided moral and educational guidance with the goal of helping the mothers become successful and independent adults.

The home was renamed the Florence Home in 1958, at which point Crogman had remarried, taking vows with a dentist, Leon C. Crogman, the brother of Ada Crogman Franklin, whose husband, Chester Arthur Franklin, founded The Call.

In the 1970s, the Florence Home merged with the Florence Crittenton Home — which previously only served white mothers — and became a racially integrated facility.

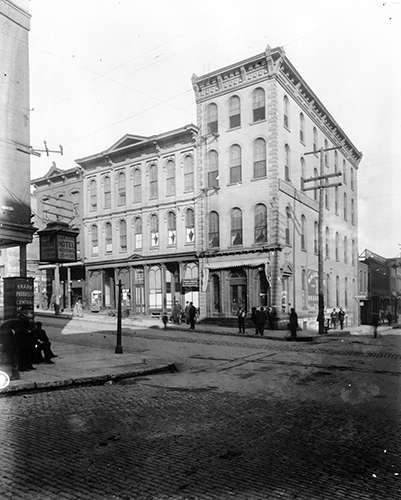

The latter was named for a New York drugmaker Charles N. Crittenton, whose daughter, Florence, died at the age of four from scarlet fever. In his grief, he founded the Florence Crittenton Home in New York to shelter “erring and wayward” women.

The New Yorker went on to establish 64 more homes across the country, including in Kansas City, which first opened in 1896 in the City Market area as a shelter for prostitutes.

After the merger of the two homes, Haar recalled the expectant mothers playing games in a community meeting room and eating meals at a dining hall. The place had a college dormitory feel, in ways.

But unlike a college dorm, there was a nurse who checked on the girls and women, and accompanied them to the hospital, where, by then, they were taken to give birth. A teacher from the Kansas City school district was also hired to help the girls keep up their education.

By the time she left in late 1972, Haar noticed numbers of residents starting to dwindle as birth control became more widely available.

“I was glad that we didn’t need the place so much anymore, but then I was sad we couldn’t keep it over for the ones who did still need it,” she said of the home, which eventually transformed into a mental health service.

Shortly after Haar left Florence Home, the women’s rights movement hit an important milestone with the passage of Roe vs. Wade, which legalized abortion in 1973.

Haar noted that the building on Campbell Avenue, which had been such an important resource historically for Black women before integration, was later torn down and made into a parking lot.

A 1992 Star article announced that St. Luke’s was acquiring Crittenton, which by then served as a non-profit mental health service for children and parents. At that point, the non-profit had been losing money.

“As a children’s charity, Crittenton is a treasured community resource that for nearly 100 years has been an advocate for children in our community,” Ed Matheny, the president of St. Luke’s Hospital at the time, told The Star.

Come 1996, the Crittenton home (which is now part of the St. Luke’s-Shawnee Mission Health System) was transformed into a mental and emotional health facility for children and their families. It still exists today.

It’s one of about half of the original 64 Crittenton homes that still exist in some form.

Crogman kept volunteering in the community nearly up to the day she died at the age of 97 on Jan. 23, 1992. She is buried at Mt. St. Mary’s Cemetery.

A Star article announcing her death recalled that some women who passed through Florence Home would later return with good news of graduations or marriages.

Rev. D.A. Holmes, of the Paseo Baptist Church, is quoted as saying in 1954, “I do not know of a woman in America superior to Elizabeth Crogman... her inspiration certainly came from heaven.”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.