All Library locations will be closed Monday, February 16 for Presidents Day.

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Anna Spoerre | aspoerre@kcstar.com & Michael Wells | lhistory@kclibrary.org

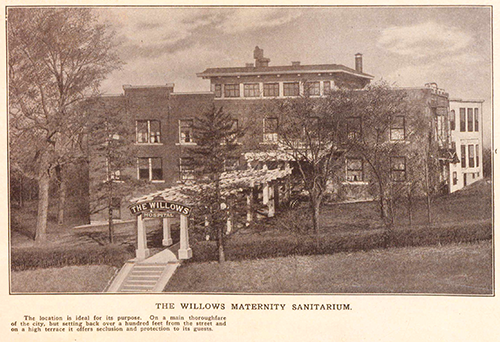

To this day, it’s one of Kansas City’s best kept secrets: An apartment complex now sits at 2929 Main Street, sprawled out between a school and a hotel, but decades ago the land on Union Hill served as the birthplace of thousands of children born to unwed mothers.

The Willows Maternity Sanitarium is scarcely known, despite its role helping Kansas City gain notoriety as an “adoption hub” of America through the mid-20th century. It’s the subject of the latest “What’s Your KCQ?,” a partnership with the Kansas City Public Library.

Women who were pregnant and unmarried in the early 1900s faced limited options and societal scorn. Many chose, or were sent, to deliver their babies and give them up for adoption in special facilities for unwed mothers — among them, The Willows.

The Willows traces its history to 1905, when husband and wife Edwin and Cora May Haworth offered their home as refuge for the unwed and pregnant daughter of a family friend. They took pleasure in offering a safe place for her to give birth away from public scrutiny and saw a larger need for an institution where the daughters of affluent families in similar circumstances could find safe harbor and connect with adoptive parents. And thus, The Willows was born.

Seclusion Maternity Service. 1937. | Kansas City Public Library

The Haworths expanded their business in 1908, buying a mansion on five acres of land on Main Street and outfitting it as a maternity hospital. In the coming decades they would be among hundreds of institutions catering to unmarried expecting mothers.

By the 1950s, more than 200 maternity homes, primarily serving daughters of white middle class families, sprang up across 44 states, according to an article by the Washington Post. In the 20 years before Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in 1973, an estimated 1.5 million unwed mothers in the United States were sent to birth and give up their children, The Post reported. Mothers were mostly teens or young women.

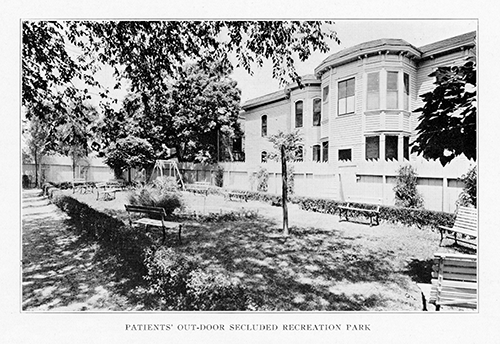

The Willows, a private operation, required a referral from a prominent doctor for admission. And patients had to be able to pay for their stay. The Haworths wanted complete control of the Willows and would not accept any form of state aid for payment.

For their part, they provided Willows guests unparalleled comfort and privacy. One former patient returning to the Willows site in 1975 described it to a Kansas City Star reporter as “the Ritz or Waldorf of homes for unwed mothers.”

Seclusion Maternity Service. 1937. | Kansas City Public Library

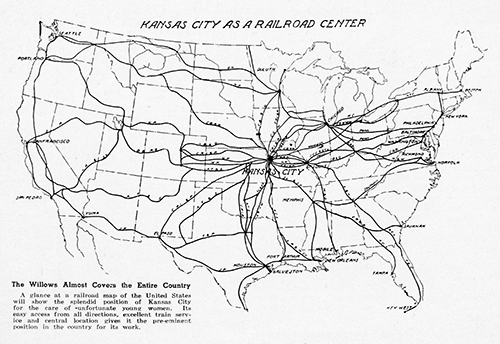

Kansas City’s central location and its railroad connectivity made it a natural adoption hub for the nation. By this time, the Orphan Train Movement was in full swing, sending children who’d been given up for adoption in the East to the Midwest via rail. This practice not only alleviated urban overcrowding; the orphan trains also helped many children in dire situations hoping to find a better life.

During the first quarter of the 20th century, it was also incredibly easy to adopt children in Missouri. Couples arriving in Kansas City often departed with new additions to their families the same day.

When the transaction was completed, Missouri’s closed adoption laws helped keep matters discrete. Once filed in Jefferson City, records were sealed — something that has hindered genealogical researchers over the years but was attractive to many adoptive parents. That remained the case until passage of the Missouri Adoptee Rights Act in 2016, which gave adoptees access to their original birth certificates.

While expecting mothers arriving to The Willows entered through the backdoor, to maintain privacy, families coming to adopt children came in by way of a steep, concrete staircase leading up to the front doors where a sign reading “The Willows Hospital” greeted them.

Carol Price was about two months old when her grandparents, the Haworths, picked her out to be adopted by their son Don Haworth and his wife, Peggy Haworth. Price recalls growing up around the Willows, spending Sunday dinners with her grandparents in a room to the side of where the expecting women ate, playing an ornate music box that sat inside the mansion and chatting with the nurses and social workers.

a maternity home for unwed, pregnant mothers that used to stand at 2929 Main Street

in Kansas City. Price was born at and adopted from The Willows, which was

founded by her grandparents | Tammy Ljungblad - KC Star

The patients ranged in age from 12 to 35, said Price, who is now 77 and still lives in the metro. She wasn’t allowed to interact with them, in order to maintain their privacy, but once she was 12 or 13 years old, she was allowed to help give the babies a bottle.

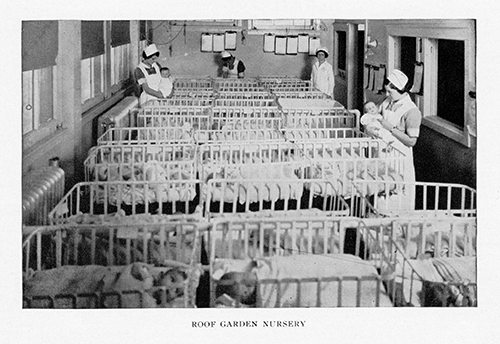

She recalled the nursery with “row after row of babies,” crying and wanting to be fed.

Once Price’s mother took the reins after the death of her grandmother, Price recalled her mother getting calls in the middle of the night from nurses saying one of the girls was homesick. Her mom would go to the girl and sit with her and talk.

“What was really special about The Willows was that everybody that worked there really cared about those girls,” Price said. “They really wanted just the best for them and wanted to make sure that they didn’t get down on themselves because of what happened.”

“It was a very loving place. That’s the way I grew up,” Price said.

Years later, KelLee Parr, the author of three books on The Willows, learned through his research that the hospital really was a well-kept secret across town.

He only learned the details of it himself when doing research on his grandmother, who came to The Willows and gave birth to his own mother on Valentine’s Day 1925.

“The more I’ve learned, the more thankful I am that my grandma was sent to The Willows because those people really cared about the girls that they brought in,“ he recently told The Star, noting that there were several maternity homes in Kansas City at the time, and not every home was as pleasant at The Willows.

Through interviews with dozens of people who passed through The Willows, Parr said he learned that while the pregnancy was often a traumatic time for the unmarried mothers, The Willows staff “were very kind in a very difficult time.”

When the expecting mothers went into town — many opting for trips to The Plaza — they were given fake wedding bands to wear so it appeared they were married, Parr said. When it was time to give birth, they could deliver at The Willows, though they could also go to a larger hospital if the pregnancy or birth was complicated.

At its peak, more than 100 mothers and their infant children took up residence at The Willows. The sanitarium endured, maintaining a high level of care, until its doors were closed in 1969.

The reason for the closure of the Willows in 1969 was simple: money. As times changed, the need for expecting unwed mothers to give birth privately was not as great, and funding had simply run out. Over its 64 years in operation, an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 babies were delivered inside its gates.

Researchers have found it difficult over the years to track down records from The Willows, in part due to the measures the state once took to ensure privacy. It also was long rumored that files had been burned by the Willows staff. Parr, the author of “Mansion on a Hill: The Story of the Willows Maternity Sanitarium and the Adoption Hub of America,” recently revealed that all records initially were offered to the Jackson County Court, which refused to accept them. Later, Parr said, out of a desire to respect the privacy of their patients and in line with the court’s decision, the records were taken to the Federal Reserve where they were destroyed.

In 2016, items collected by former Willows nurse Florence Beal Bolte were donated to the Kansas City Public Library. Price also donated many remaining items from The Willows, including statistics, brochures and books, to the Jackson County Historical Society. While patient records are gone, the collections are a wonderful resource for those interested in learning about the history of the hospital.

“It’s amazing to be able to say I was part of The Willows. I’m very proud that I was and I’m very proud of my family,” Price said. “It just makes my heart feel so good to know what my mom and my grandparents did for other people.”

In the coming months she is hoping to erect a historical sign, backed by the Historical Society of Jackson County, at the old site of The Willows. That way, if anyone comes searching for their birthplace, they’ll again be able to find it.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.