Kansas City mafia? ‘Oz’ park or toxic dump? Were missiles buried nearby? Your 2020 KCQs

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Savanna Smith

In this strange year, “What’s your KCQ?” readers had a lot of questions. And surely, headed into 2021 with the pandemic still raging and a vaccine on its way to all, there will be more.

Do you have a question about how the Kansas City community has changed? Or what you can look forward to with the new year? Maybe a query about local lore?

Whatever is on your mind, we’re in this together and looking forward to answering your most pressing questions and curiosities.

You can ask us here, or email kcq@kcstar.com.

To get your wheels turning, here’s a look back on what was asked, and answered in 2020 — both timely and mysterious.

Our team — The Star and the Kansas City Public Library — answered more than 50 questions this year.

You asked about how the coronavirus pandemic would affect your daily life, the history of Mill Creek Parkway after summer protests restored the roadway’s name, and how to vote in the 2020 election.

We answered the tough questions, but also had fun unearthing quirky tales. We told the story of , the swinging bridge in Swope Park, and the steep cliffs and ‘speed maniacs’ of Cliff Drive.

Here are four of our favorite KCQ stories from 2020. We’ll start at the beginning just weeks before a Chiefs Super Bowl win, and end with a look at the Kansas City mafia (by way of Chicago).

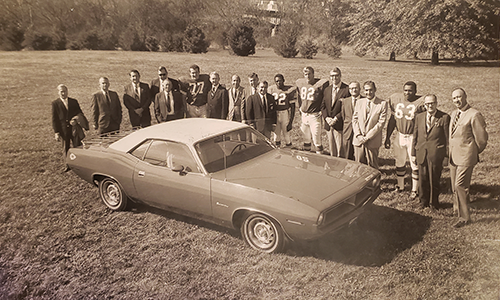

Where’s the Chiefs-autographed Barracuda from 1969?

By Randy Mason | Originally published Jan. 10, 2020Picture a high, wobbly punt. The football twisting and turning, taking a few crazy bounces before it rolls across the goal line.

That’s the sports equivalent of our KCQ quest to find an autographed car known as the Cuda Chief.

car after practice in the fall of 1969. Rod Hanna

Lewis Jones recalls that sometime in the fall of 1969, a Plymouth Barracuda, autographed by everyone on the team, was given away at a Chiefs game. He’d like to know what became of the valuable sports collectible.

So we went to work. The assignment sounded easy enough. We found a few photos WDAF-TV had posted on Facebook that show the Cuda Chief on display outside the station. And an article from what appeared to be a Chrysler/Plymouth dealers newsletter extolled the promotion’s success — but didn’t include the winner’s name.

belongings behind the Cuda Chief, August 1972. Beth Biddison

We finally tracked it down. But what ensued was a bit confusing. We tracked all the way to a Wilmington car lot — and the journey was quite interesting.

So here’s the rub. Without a VIN, or the kind of paperwork that no one seems to have kept, any further stops beyond that Wilmington car lot would be awfully hard to track. Then again, if the Chiefs can come roaring back from 24 points down, who’s to say the rest of this muscle car mystery can’t be solved?

Read this full story here.‘Oz’ theme park? Toxic dump? Fireworks in history of Sunflower ammo plant

By Dan Kelly | Originally published May 20, 2020Back in 1942, the federal government uprooted 150 farms in northwest Johnson County as well as the entire town of Prairie Center so it could build an ammunition plant.

All production at Sunflower stopped in 1992. N.d. KC Star File Photo

That’s the kind of sacrifice folks endured for the good of the country during World War II.

Michael Rieke’s asked: “What’s the story of the WW2 Sunflower ammunition plant outside of De Soto, what company built it, what kind of ammunition it made, etc.?”

The plant went on to churn out ammo for three wars, leaving a toxic wasteland in its wake. Over the years developers promised to clean it up for all sorts of endeavors: a bioscience lab, shops and homes, and even a “Wizard of Oz” theme park.

unlike any other — but some questioned whether its founder could pull it off. In late 2001,

Johnson County commissioners killed the Oz idea. The resort was planned for the former

Sunflower Army Ammunition Plant near De Soto, Kansas. Artistic renderings provided by

Oz Entertainment Co. 1999. OZ ENTERTAINMENT CO.

First things first: The original name was Sunflower Ordnance Works, but it was changed to the Sunflower Ammunition Plant in 1963. Owned by the federal government and operated by Hercules Powder Co., a subsidiary of Du Pont, it began producing propellants for small arms, cannons and rockets on March 23, 1943, less than a year after construction began.

Read this full story here.Is it true that missiles were buried near Kansas City?

By Randy Mason | Originally published Nov. 13, 2020The Cold War years were fraught with tension. It was a time of global gamesmanship and military staredowns.

And it sets the scene for a question that Kenneth Goodwin submitted. He asked if it was true that ballistic missiles had been buried along Van Brunt Boulevard near Linwood Boulevard in the early 1960s.

It sounded unlikely. But those were strange days. So we checked around. Military and government records, old newspapers. No sign of nukes on Kansas City’s East Side.

James Stemm, director of collections at the Titan Missile Museum in Green Valley, Arizona, confirmed that if nuclear weapons were ever there, “the Army and Navy didn’t know about them.”

But he pointed out there were some stashed nearby.

For years, ICBM silos dotted the countryside around Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri and Forbes Air Force Base near Topeka. They held powerful Titan II and Minutemen missiles, the kind that scared everyone in the 1983 movie “The Day After.”

Now, Nike Elementary School carries the name.

GARDNER HISTORICAL MUSEUM

Eventually, those installations were phased out and relocated.

But an earlier generation of missiles — the Nike-Hercules, once crept even closer to the edge of the metro. These were, according to Stemm, “armed with nuclear warheads.”

By the late 1950s, as tensions with the Soviets grew, cities across the country sought ways to fortify themselves. One such result was the creation of the Kansas City Defense Area in 1959.

It included four bases armed with Nike missiles — Pleasant Hill and Lawson to the east, with Fort Leavenworth and Gardner on the Kansas side. A command center operated out of the Olathe Naval Air Station..

Read this full story here.Is ‘Fargo’ season 4 based on true Kansas City mafia-like crime?

By Rob Owen - Special to the Star | Originally published Sept. 24, 2020The new season of “Fargo” is set in 1950 Kansas City, and an image of the old skyline does make an appearance.

Even some icons of Kansas City history, including Union Station and the stockyards, figure prominently in the plot.

But the entire season was filmed in … Chicago.

which in real life held power for decades. In “Fargo,” they’re challenged in the

1950s by the up-and-coming Black crime syndicate. Elizabeth Morris FX

Every episode of “Fargo’‘ starts with a claim that it’s based on a true story, but of course it is not. Executive producer Noah Hawley says the new season is not inspired by any real Kansas City mob history.

“I did some reading. There is a Jackson Democratic Club there that was sort of a headquarters,” he says, “but I didn’t really base (this season) on anything.”

Production designer Warren Young said his research into the real Jackson Democratic Club, an unassuming brick building still standing at 1908 Main St., led to an effort to match its architectural style to the headquarters building of the leading gang in “Fargo.”

in the gangland of 1950 Kansas City. Matthias Clamer FX

The old Kansas City stockyards in the West Bottoms are another real-world location that plays a part in “Fargo.” Cannon’s gang battles the Italians for control of them in the first few episodes.

And the notorious Union Station Massacre of 1933 helped inspire a pivotal scene in the latter half of the season.

Read this full story here.Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.