Free to Create, These Four Kansas Citians Made History

As a continuation of the Library’s reflection on, and celebration of, creative freedom, the Library recognizes four historical Kansas City figures. They exercised their imaginations and summoned great ingenuity — in some cases bravely and against social norms — to better themselves, their professions, or the lives of others.

Because they were free to.

(Lena) Nora Douglas Holt, 1885-1974

Renowned composer, singer, pianist, and music critic Nora Holt broke the boundaries of what was expected of her race and gender.

Born Lena Douglas in 1885 in Kansas City, Kansas, she began playing piano at age 4 and eventually became the organist for her father’s AME church. In 1917, she graduated with a degree in music from Western University in Quindaro, Kansas, the first Black college west of the Mississippi. She earned a master’s degree in music from Chicago Musical College — the first Black woman to do so.

Previously married and divorced three times, Lena married George Holt, a successful Chicago hotelier, in 1916 and began using the name Nora. Around that time, she was a music critic at The Chicago Defender, one of the nation’s most respected Black newspapers. With pianist Henry Grant, Lena founded the National Association of Negro Musicians, which is still in operation today. She also briefly published her own magazine, Music and Poetry.

Two years into their marriage, George Holt died, leaving Lena independently wealthy. She moved to New York and joined in the thriving Harlem Renaissance. While there, she married Joseph L. Ray, an assistant to steel magnate Charles M. Schwab. Ray expected his new wife to settle down with him in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. In answer, she divorced him.

Lena traveled the world performing, then settled in Los Angeles in the 1930s, but continued to headline for long periods in Asia. She returned to New York in the following decade, writing for the Amsterdam News and the New York Courier, and became the first Black person to join the Music Critics Circle in 1945. She took to the airways in the 1950s and ’60s as host of an annual “American Negro Artists” show on radio station WNYC and “Nora Holt’s Concert Showcase” on Harlem's WLIB.

While few copies of her compositions remain, her legacy as a trailblazer in music and Black culture endures.

George C. Hale, 1850-1923

Kansas City fire chief George C. Hale was once known as the world’s most famous fireman. Not only did Hale patent more than 60 fire-fighting inventions, but he was also chosen to represent the United States on the "American Fire Team" at the International Fire Congress in London in 1893. In front of the lord mayor and royalty, he led the Kansas City Fire Department to a first-place victory.

Hale arrived in Kansas City in 1863 at the age of 14 and began working in a machine shop. He helped build the Hannibal Bridge and volunteered in 1867 with the fire company, running ahead of the fire wagons with a lighted torch. By 1882, he was the chief.

During his 31 years of service with the fire department, Hale developed numerous methods and devices that enabled firefighters to arrive at fires quickly and fight them effectively. He invented the water tower, an immense contraption pulled by three horses that was capable of shooting 5 1/2 tons of water per minute, and the automatic fire alarm, which alerted a city’s central fire station to a fire’s location.

Hale continued to invent and manufacture fire-fighting equipment until his death in 1923.

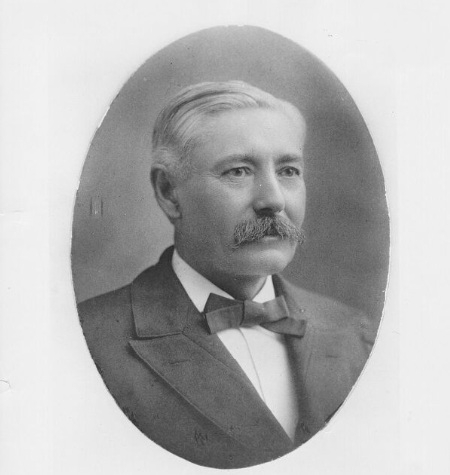

James M. Greenwood, 1837-1914

At a time when many Kansas City residents considered educating children optional, James Greenwood, who ultimately served as superintendent of the Kansas City Schools, changed that perception.

Greenwood moved with his parents from Illinois to Missouri, dividing his boyhood between farm chores and attending the nearest school, which was seven miles away. He was a voracious reader and made his way through all of his school’s textbooks. He was able to purchase a collection of volumes containing the classics, algebra, geometry, and philosophy from a neighbor’s estate by selling a steer.

He attended the Methodist Seminary in Canton, Missouri, then read law with two uncles. After serving with the Missouri State Militia in the Civil War, he taught in Illinois, Kirksville, Missouri, and, in 1874, Kansas City.

As the superintendent of schools, he developed good relations with the press, which aided him in fighting the growing opposition to public schools. He worked tirelessly to improve daily attendance and successfully raised enrollment before the state passed mandatory school attendance laws. By keeping statistics on every school, Greenwood demonstrated that education benefits children of all races and economic levels.

He wrote many textbooks and, in 1898, served as the president of the National Educational Association. He stayed on as an advisor to the school board after his retirement in 1913. By the time of his death, he was known nationally for his contributions to the field of education.

Greenwood became the first director of the Kansas City Public Library in 1873 and directed the construction of the original Library building in 1889 at 8th and Oak. He was committed to making its services available to the public for the rest of his life.

Cloteele T. Raspberry, 1910 – 1994

Born in Texas, Cloteele T. Raspberry moved to Kansas City at a young age and became a fashion designer and mentor to young women interested in the profession. Raspberry graduated in 1927 from Lincoln High, where she stood out in her sewing class, and eventually earned an associate’s degree from Isabelle Boldin’s School of Fashion Design.

As a self-employed dress designer, Raspberry joined the National Association of Fashion and Accessory Designers and traveled nationwide, showcasing her work at designer events. Later, the organization chose her to lead teenage members in organizing their own fashion show fundraiser.

Raspberry was also a 25-year member of Kansas City’s Urban League Guild and served as a Sunday school teacher for more than 35 years at Paseo Baptist Church. She died at the age of 83 in 1994, leaving her husband, William, and daughter, Villa, as well as a Kansas City legacy of more than 70 years.