A Missouri Author's New Book Widens the Path for Women of the Santa Fe Trail

This story first aired on KCUR 89.3 on February 28, 2025. All photos courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis.

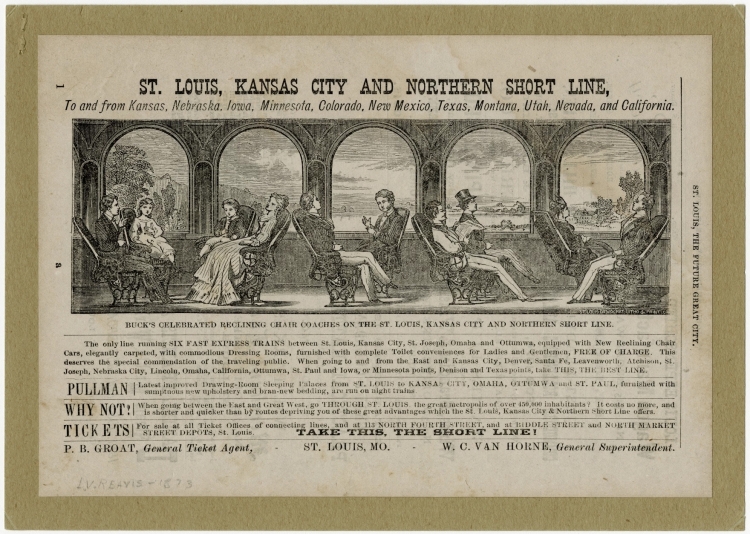

The author of a new book about women on the Santa Fe Trail, which starts in Kansas City and is considered America’s first great international commercial highway, is well aware of how people often think of women who made the journey: fearful, sun-bonneted white women in wagon trains, reluctantly leaving behind their comfortable lives on the East Coast.

But in her new book, Crossings: Women on the Santa Fe Trail, St. Louis-based author Frances Levine tells the stories of women of many backgrounds, each with her own reason for traveling the trail between New Mexico and Missouri.

Just like women today, some appeared to be fully in charge of their lives, and others had very little control.

“If we look at sort of a wide-angle lens on Western history,” she says, “we'll see that … oftentimes, women had to move their families looking for new opportunities, and so they were the primary decision makers, in some cases, of moving their families west.”

At the opposite end, the most fearful women on the trail were likely not white, high-society ladies torn from posh parlors, as sometimes portrayed in fiction.

“I didn't expect to find so much about Native enslavement and the trafficking in women and children,” Levine says.

She writes that Native peoples and Europeans trafficked humans in a variety of settings, enslaving them, trading them in hostage exchanges, taking them as sexual partners or exploiting their skills as laborers and translators.

Though the trail legally opened in 1821, when Mexico won independence from Spain, Levine’s work excavated stories going back to 1760.

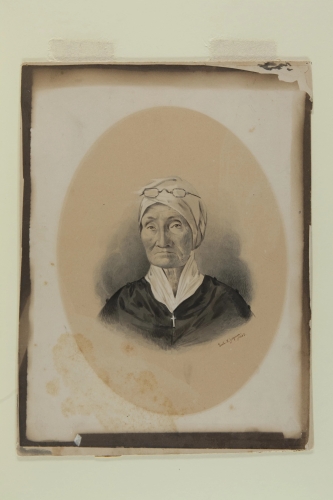

That was the year a group of Comanches kidnapped María Rosa Villalpando Salé dit Lajoie and 55 other women and children from their compound in Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico.

Her name itself is a trail, Levine suggests.

Villalpando Salé dit Lajoie started out as a member of the Hispanic community in northern New Mexico, then became a Comanche captive, a Pawnee captive, and later a member of a French Creole community where she gained social standing and owned real estate, firearms, furs, a store and slaves. She died in St. Louis at more than 100 years old.

Levine, who earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from Southern Methodist University, first ran across Villalpando Salé dit Lajoie in another book. In it, Villalpando Salé dit Lajoie was a mere footnote and blamed for her own capture.

Levine writes that the book embellished and romanticized the story of the raid, “claiming it was in retaliation for her refusal to marry a Comanche chief, a union supposedly arranged by her father when she was a child.”

The more Levine searched, the more she saw that Villalpando Salé dit Lajoie’s story encapsulated much of what women of the era experienced.

Levine found her story so illuminating that she has more entries in the book’s index than anyone else and jokes that “Maria Rosa Villalpando is very disappointed that this whole book is not about her.”

Levine now makes her home in St. Louis, where traveler and merchant supplies were aggregated and shipped west along the trail. She is the past president of the Missouri Historical Society. Before moving to this end of the trail, she helped preserve history at the other end: She was the former director of the New Mexico History Museum and Palace of the Governors, in Santa Fe.

She writes that making the move from one end to the other allowed her to “explore the complexity and depth of the links between the Southwest and the American heartland” and the “evolution of women’s roles in interregional travel and intercultural exchanges.”

Her office at the Missouri Historical Society occupied the same space as did the society’s head librarian from 1913 to 1943, who edited one of the trail’s most significant woman-authored journals.

The librarian, Stella Drumm, had corresponded with journal writer Susan Shelby Magoffin’s daughter. Levine found a box with those and other papers, which appeared not to have been disturbed since the 1940s.

The information in Magoffin’s Down the Santa Fé Trail and Into Mexico, still in print, was plentiful, but other evidence of the female experience on the trail took a great deal of digging to find.

“I had to look for women in other contexts,” Levine explains. “I had to look for them in store records, census records, property maps, wills and lawsuits.”

She struggled especially to find particulars about enslaved women — Levine says she didn’t think she’d find anything at all. Once she did, it took the form of diary entries written by other people — an enslaved woman’s existence reduced to what captured someone else’s attention on any given day, she says.

Magoffen’s diary includes entries about the woman she enslaved, named Jane.

She “writes about Jane's misbehaving at the same time that she's writing about her own fears about being on the trail, but she's not recognizing that Jane may have had her own set of fears,” Levine explains.

Levine says that examining women’s parts in this history can also reveal a failure to recognize families, very often multiracial or multicultural.

But it was the family-making and everything else that the women carried that shaped American culture, particularly through the middle of the nation.

“What we need to do,” Levine says, “is to teach history in a slightly different way, from a different perspective, sometimes taking a more community perspective. … look at the way in which people moved with their cultures, the way in which they brought their own cultural practices, their own food ways, their own heritage with them along the trails.”

This story was produced in partnership with the Kansas City Public Library.

Frances Levine discusses Crossings: Women on the Santa Fe Trail at 6 p.m. on Tuesday, March 4, at the Plaza Branch, 4801 Main St., Kansas City, Missouri 64112. The event is free with RSVP.