Former Hallmark Artist Pedro Martín Shows Being a 'Mexikid' Can be Universal

This story was produced in partnership with KCUR and first aired on KCUR 89.3 on October 4, 2024. To hear the audio, click here.

Retired Hallmark artist Pedro Martín created a graphic memoir that seems to resonate with everyone who picks it up, though the way he describes Mexikid doesn’t initially sound universal.

“When I was about 13 years old,” Martín says, “my parents crammed all 11 of us — I have eight brothers and sisters and my mom and dad — into this Winnebago Chieftain motorhome and a pickup truck with ropes for seatbelts, and took us on this epic 2,000-mile trip down to Jalisco, Mexico, to get my super ancient grandfather and bring him back to live with us in the United States.”

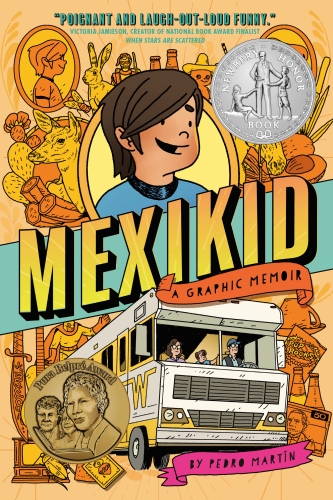

In its first year in print, Mexikid has received numerous awards, including a Newbery Honor, the Pura Belpré, the Eisner Award and the Tomás Rivera Award.

Though the story is specific to his family, Martín says it echoes an experience many have as children.

“One of the (reasons) that crosses across all the demographics is this idea of being — and this sounds bad — being held hostage by your parents,” Martín says. “As a kid, you don't have a vote on these trips.”

He and his siblings certainly didn’t. Nor did they have a vote on how to shoehorn another person into their already crowded house.

In the book, young Pedro protests to his mother, drawn walking through the house carrying a giant basket of laundry. She replies in Spanish, translated in a footnote, that they’ll make room for the grandfather, and the discussion is over.

But in a house brimming with siblings, it’s easy to find someone else to complain to.

“What if he doesn’t like us?” Pedro asks. “Does he even like Star Wars? … It’ll be an awkward staring contest that will last forever.”

His sister’s answer sets up the rest of the story: “Dude! Star Wars has nothing on the life Abuelito has led. You should take advantage of the situation and learn about him.”

Martín says he's heard from readers that they only knew about the places their families came from through their parents’ stories and hadn’t always gotten the chance to hear from older relations, like grandparents.

He says people have approached him with comments like, “Yeah, I went to these places, but I didn't understand them until I was there and years passed, and I really started to understand what this place was, and how it was special.’ So that all kind of played into people finding themselves in the story.”

Throughout the book, Martín is finding himself as well.

With the bird’s-eye view perspective of a graphic novel, he simultaneously shows what is preoccupying the family’s children and its adults. The near-constant juxtaposition reads like the author’s brain working through questions of identity.

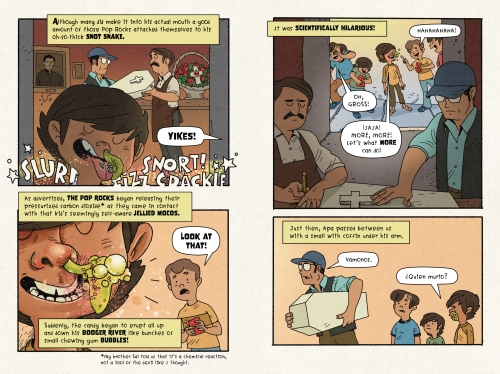

In the book’s most iconic scene, a few of the young siblings stand in the foreground, obliviously enjoying Pop Rocks, while their father selects a coffin in the background.

The kids have internalized an instruction that, in Mexico, they should be nice to everyone they meet; strangers are either unknown relatives or people who might be able to help them later. They therefore agreed to share their Pop Rocks with a boy they think might be their cousin.

“As he gets closer, I start noticing he's got this just gigantic booger just hanging out of his face,” Martín says, explaining the scene. “Well, of course, the Pop Rocks get into the snot, and the liquid in the snot activates the Pop Rocks, and it just starts bubbling and bubbling, and it starts making these gigantic, bubblegum bubbles on his face.”

The reader sees the father’s coffin purchase several frames before the kids have a clue what he’s been up to. The two scenes join when the father walks between the boys carrying the box, and they all walk back to their vehicle.

And that’s when story-Pedro starts to see his family, and himself, in a whole new light.

His father talks about the siblings he lost and the circumstances of his mother’s early death. He got the coffin to rescue her skeleton from an underground river that has shifted course and is flooding the cemetery where she’s buried; the family must move her before Abuelito can leave for the United States.

As he talks to groups about Mexikid, Martín encourages readers of all ages to record moments in their days, even if they don’t seem as pivotal as relocating the remains of an ancestor.

“There are universal specifics that kind of pop out of, just, experiences — like, we all fall down, and then let's talk about falling down,” he says. “It is a magical experience when people come back at you, like, ‘Yes, something similar happened to me,’ and then they tell that story.”

Pedro Martín discusses Mexikid at 10 a.m. Saturday, October 12, during the Heartland Book Festival. The event is free with RSVP. More information at HeartlandBookFest.org.