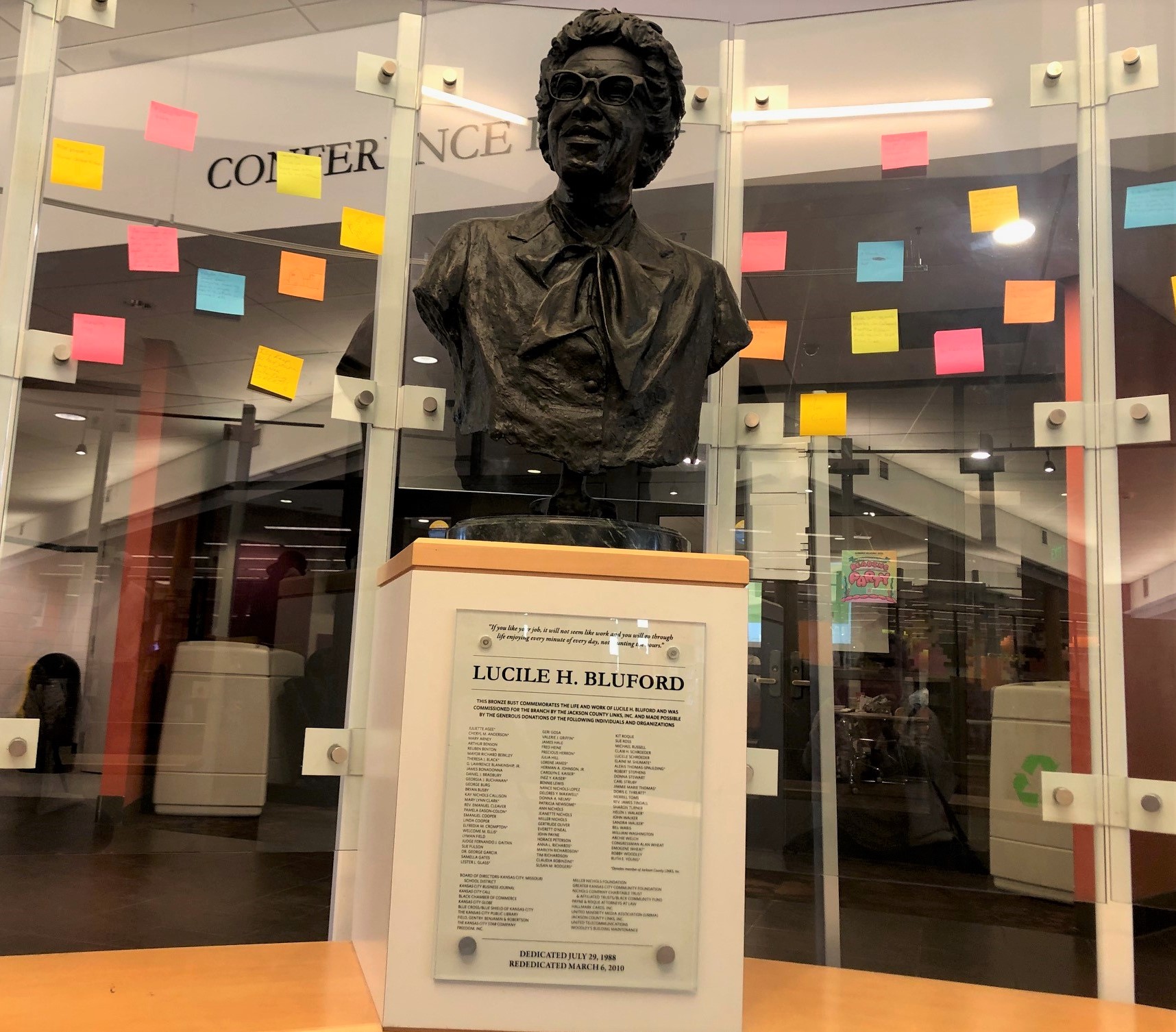

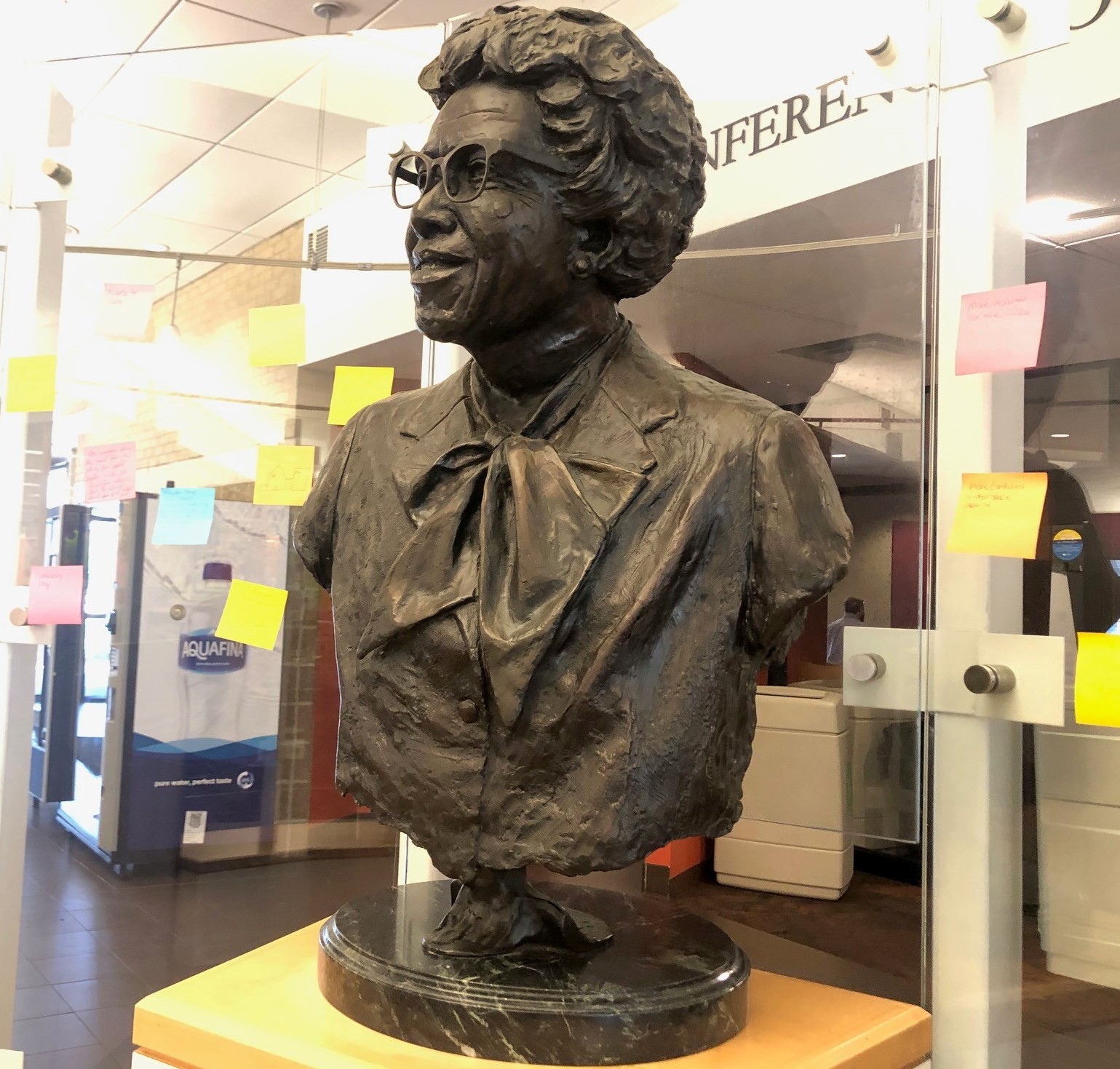

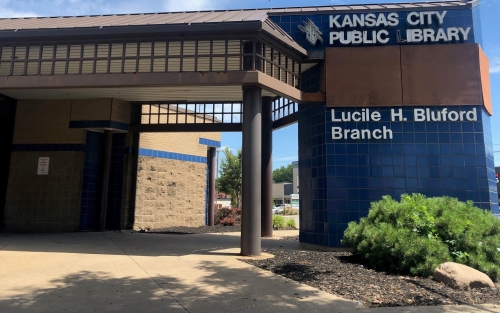

The Kansas City Public Library opened the Lucile H. Bluford Branch in 1988. The location at 3050 Prospect Ave. is named for Bluford, a civil rights leader and longtime editor of The Kansas City Call.

“I think she was pleased," says Tracy Allen, editor-in-chief of The Call since June 2023, "but she was more focused on, you know, you can give me the flowers after I'm gone."

She adds, “When you looked at Miss Bluford, you thought, ‘Okay, this is a celebrity.’ But she never came across as that.”

Bluford started at The Call as a copy editor, then a cub reporter, desk editor, city editor, and in 1938, managing editor. She took on the role of editor-in-chief after founder Chester Franklin died in 1955, and in 1983, as owner and publisher of the newspaper.

The Library celebrates Bluford’s impact on Lucile Bluford Day, designated as July 1 by the state of Missouri in 2016.

Like Bluford, Allen also worked her way up at The Call. After writing for a handful of other newspapers, including The Kansas City Star, she was hired as a general assignment reporter at The Call in 1998 and worked with Bluford until she died in 2003.

“And one of the things that I can remember, and (the late publisher) Donna (Stewart) was really big on this, is that people that were coming on staff get to know who Miss Bluford was,” recalls Allen, “and why she championed causes surrounding not just only the Black community, but communities of color.”

That’s a tradition that Allen continues to this day.

The Library recently acquired access to The Kansas City Call digital archive, from 1919 - 2008.

“The Call has the distinction of being one of the longest running and preeminent Black newspapers in the country,” says Jeremy Drouin, the Library’s special collections manager. “The value of being able to full-text search The Call archive going back to the newspaper’s founding in 1919 cannot be overstated, as it is a record of Black life, culture, and community in Kansas City.”

Drouin adds that having digital access is “a boon for researchers, who previously had to sift through reels of microfilm to find articles relevant to their research.”

Allen considers it an important resource, a means of looking back “to see the struggles that Black people went through during the Jim Crow days and then, of course, the Civil Rights Movement.”

“And The Call was there, it was at the forefront,” she says, “And we would like to continue to stay at the forefront.”

“She was such a powerhouse for justice,” says Bluford Branch manager Sunny Branick about Lucile Bluford. That’s something, he says, that shapes the staff's day-to-day interactions with patrons.

“Every day is kind of like: how do we do justice today?” he asks. “We're just always grappling with that, and thinking: How can we be better? How can we better serve people?”

More about Lucile Bluford

Biography

Born in North Carolina in 1911, Lucile Bluford moved with her family to Kansas City when she was 7. She would become one of its most accomplished and beloved citizens.

She fell in love with journalism while working on the newspaper and yearbook at Lincoln High School, where she graduated first in her class in 1928. With access to the University of Missouri and its famed journalism school blocked by the school’s refusal to admit African Americans, Bluford attended the University of Kansas, graduated with honors, and launched a reporting and editing career that eventually took her to The Call (where she’d worked summers during college).

She continued to push back against MU’s segregation policy. Backed by the NAACP, Bluford repeatedly applied for admission to its graduate program in journalism and filed several lawsuits. Missouri’s Supreme Court finally ruled in her favor in 1941, ordering the university to admit her because there was no equivalent program at all-Black Lincoln University. Mizzou subsequently closed its graduate program, claiming professors and students were being siphoned away by World War II.

Bluford never took a class at MU, but her fight helped nudge the school toward integration. Mizzou was forced to establish a journalism school for African American students at Lincoln and admitted its first Black student in 1950. The university would honor Bluford decades later, the journalism program awarding her its Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism in 1984 and the school conferring an honorary doctorate in the humanities in 1989.

Bluford went on to a 69-year career with The Call, moving from reporter to city editor to managing editor and finally editor, owner, and publisher. She made the weekly newspaper a prominent voice for African Americans in the city and a force in the fight against discrimination.

The Library named its branch on Prospect Avenue for her in 1988. In 2002, a year before she died at age 91, the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce named her Kansas Citian of the Year.

Read more about Lucile Bluford’s legacy

Courtesy Missouri Valley Special Collections

Listen to audio from a past Signature Event or dive into research

Lucile Bluford: Her National Closeup

In this Library program from 2018, Sheila Brooks examined Bluford’s life and pioneering work in a discussion of her book Lucile H. Bluford and the Kansas City Call: Activist Voice for Social Justice, co-authored with Howard University’s Clint C. Wilson II.

A Leading Figure in Kansas City Black History

Lucile Bluford is one of the notable Kansas Citians profiled on the award-winning Kansas City Black History website, a project dedicated to exploring African American cultures and community in our region. Read her profile and explore the digital resource at kcblackhistory.org.

The Pendergast Years: Kansas City in the Jazz Age and Great Depression

The Library's historical website has a digitized collection of documents from the National Archives at Kansas City, Missouri, related to the lawsuits that Bluford pursued against S.W. Canada, the registrar of the University of Missouri, for repeatedly denying her admission to the university.