Spirited happenings: What’s Your KCQ? investigates the story of John Harvey Mott

“What’s your KCQ” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Sara DeCaro | LHistory@KCLibrary.org

A reader helped us get into the Halloween spirit by asking, “Did Spiritualism ever become popular in Kansas City?” The What’s Your KCQ? team found that not only did the movement gain followers here, it also caused a scandal that made national news.

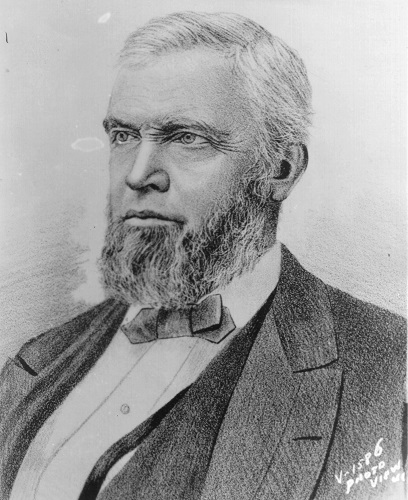

In 1881, Col. Robert Van Horn published an article, Philosophy: The New Hypothesis, in The Kansas City Review of Science and Industry. Van Horn, a publisher, congressman, and former mayor of Kansas City, had a distinguished record of service as a Union officer during the Civil War. He had also experienced personal tragedy beyond the horrors of war: He and his wife had four sons, only one of whom would outlive him.

Van Horn was curious about life after death, but science was not answering his questions. In his article, he wrote that humankind needed to find life not in “animal and vegetable alone,” encouraging his readers to seek answers beyond our scientific understanding.

Van Horn might have been thinking of a specific experience when he wrote this essay. He had recently visited a medium — not that unusual for the time. The last half of the 19th century was the heyday of the Spiritualist movement. Mediums claimed they could summon and talk to the dead and advertised their skills throughout the country. Kansas City was no exception.

Spiritualism had philosophical roots in the Second Great Awakening, a 19th century religious movement that sparked renewed interest in the spiritual world, and the direct link to the spirit world mediums offered was treated seriously by believers. Several well-known intellectuals and prominent citizens, like Van Horn, were drawn to it.

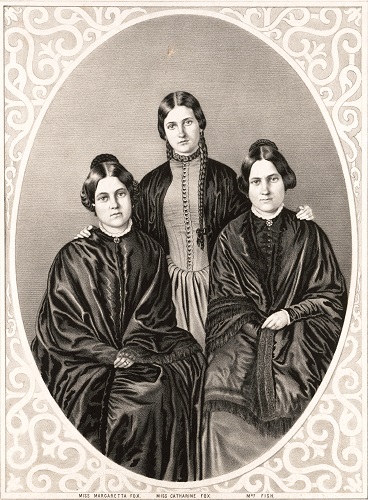

The movement really took off in 1848 when Maggie, Kate, and Leah Fox, three sisters from upstate New York, claimed that a ghost haunted their farmhouse and spoke to them through knocking sounds. Their séances were a hit, and the trio embarked on a national tour. Other mediums followed. Some were sincere believers. Others no doubt observed the success of the Fox sisters and saw dollar signs.

After the Civil War, the popularity of séances and clairvoyants soared. Few had survived the war unscathed. People were grieving and sought comfort where they could find it. Mediums offered them the chance to communicate with lost loved ones.

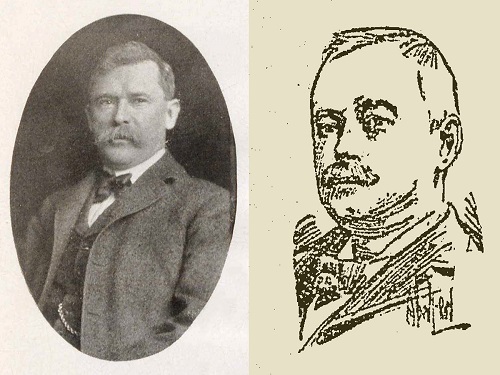

Kansas City, which was rapidly transforming from a rough frontier town to a city on the make, was a ready market. One medium in particular, John Harvey Mott, became successful enough to attract national attention.

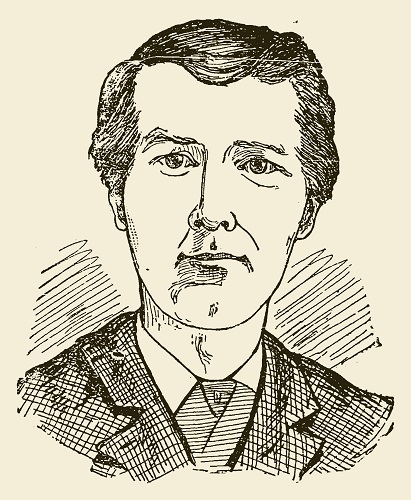

Born in Memphis, Missouri, around 1845, Mott was the son of a blacksmith. Friends and neighbors recalled him being troubled as a teenager and sometimes fleeing in terror from his house at night, claiming someone was chasing him. On other occasions, he walked around the empty store where he worked, puzzled, insisting that some unseen person had just been in the room with him.

Strange things were also reported inside the family home. People heard knocking sounds and saw furniture rattling. Others noticed shadowy figures lurking outside.

Mott claimed to want nothing to do with the supernatural world, but his employer was a Spiritualist and was certain the spirits had selected the young man as a medium. Ultimately, Mott got into the séance business.

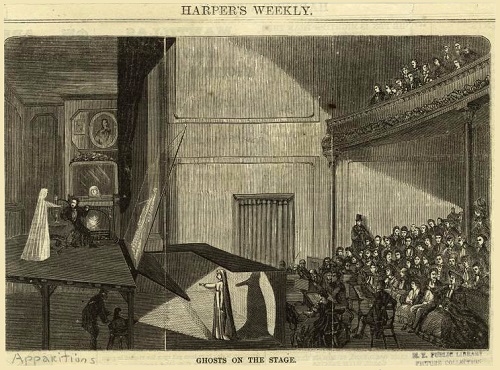

He was a “materializing” medium – rather than simply interpreting knocks, he conjured visible apparitions that conversed with his customers. Newspaper accounts in the 1870s described a hallway curtain or, later, a cabinet with an opening. Mott sat behind the partition, and his customers formed a circle and would sing. The lights were dimmed, the curtain or cabinet was opened, and the faces of dead friends and relatives seemed to appear.

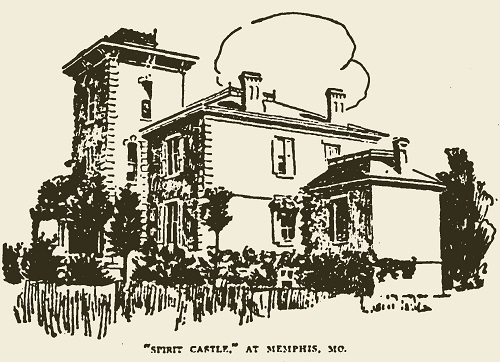

The supernatural nature of Mott’s talents might be questionable, but his ability to deliver a spectacle must have been superb. Visitors flocked to his home in Memphis. The train station bustled, and local hotels filled with believers hoping to see the medium.

Customers described entire conversations with the dead. One account had Mott presiding over a “spirit wedding” with another medium helping him summon a deceased bride and groom for the ceremony.

Not everyone was convinced. In 1878, after skeptical accounts in the press, three visitors from Illinois snuck aniline dye into a séance and squirted it into Mott’s cabinet. They heard cursing, and a surprised Mott emerged with red splatters on his body.

Accounts of the incident appeared in The New York Times and other newspapers nationwide. Mott sought a fresh start, decided to try his luck in a big city, and by 1884 had found the headlines again – this time in The Kansas City Star.

Mott relocated to a house on East 15th Street in Kansas City and began hosting séances. The Star reported that he was a hit among curious and affluent Kansas Citians who could afford his services.

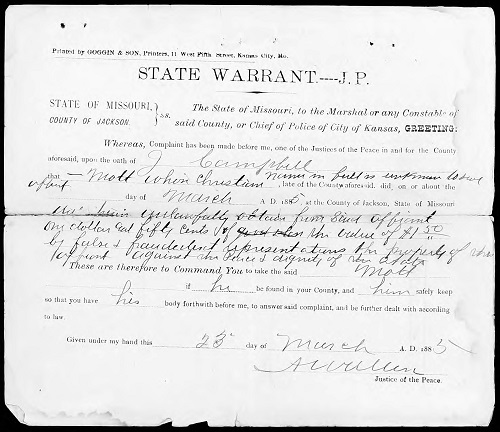

On March 25, 1885, J.B. Lawrence of The Kansas City Journal attended a séance. Like the three truth seekers in Illinois some seven years earlier, he had a concealed quantity of dye. And he carried an arrest warrant. Just as an associate quietly let two police officers into the room, Lawrence approached Mott’s cabinet and squirted the dye into the materializing spirit’s face.

Mott was seated when the cabinet door was opened and claimed to have been unconscious. But he was covered with dye. That was enough for the police, who arrested him for fraud.

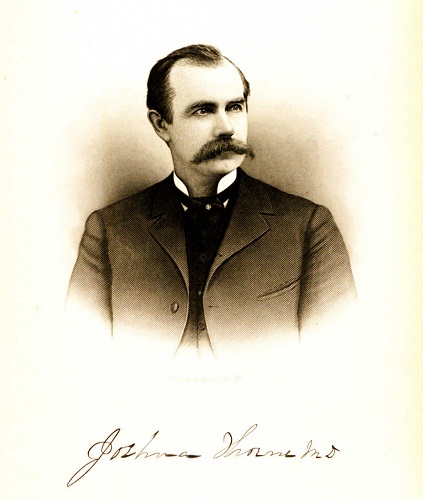

Mott’s attorneys, John W. Beebe and Washington Adams, subpoenaed several local “men of good horse sense” in his defense. One was Joshua Thorne, a surgeon who had served with Col. Van Horn during the war. He testified that he regarded Spiritualism as “a religion in the highest sense of the word.” Along with the Van Horns, Thorne and his wife were customers of Mott. He testified that the medium had even “materialized” the spirit of Col. Van Horn’s deceased son Charlie on one occasion.

However, his assessment of Mott wasn’t very helpful to his case. During his third session with the medium, Thorne said, he believed he saw Mott’s face among the ghostly apparitions and heard him cough from inside the cabinet. He testified that he felt disgusted by what happened and had stopped attending séances as a result.

Trial testimony also made it clear that Mott’s wife Mary had aided her husband’s schemes. If customers attempted to shine lights into the cabinet, she would stop them and warn that it could kill her husband while he was in his spirit-induced trance. She also refused to open the cabinet for police investigators.

Despite the evidence, after three days, Judge J.T. Clayton acquitted Mott. In his ruling, he said he neither embraced Spiritualism nor wanted to put it on trial, pointing out that while all the witnesses believed him to be a fraud, they had attended his séances “of their own free will.”

Despite the acquittal, Mott’s reputation never recovered. He returned to the family home near Memphis, Missouri, on a stretch of road known by locals as “Spirit Ridge.”

The popularity of Spiritualism went into decline shortly thereafter. Vigilant skeptics made a sport of publicly debunking mediums. In 1888, Maggie Fox admitted that she and her sisters had faked their séances.

Mott passed away in 1890, just a few years after his trial, and faded into obscurity. He is buried in the Memphis Cemetery under a simple headstone that gives no indication he was once the most famous, or infamous, medium in Missouri.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.