“What’s your KCQ” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Michael Wells | LHistory@KCLibrary.org

Kansas City culture wouldn’t be the same without fall fairs and festivals. But what’s celebrated and by whom has changed a great deal throughout the city’s history.

An alarmed reader recently wrote to What’s Your KCQ?, a collaboration between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star after running across a souvenir from an 1895 parade in the city on eBay. The antique was a remnant of the Priests of Pallas (POP) parade and included the letters KKK.

The KCQ team quickly assured our reader that the letters did not represent that KKK, but something else entirely.

Kansas City in the 1880s was struggling to shed its frontier image, and the city was filled with a sense of boosterism. Professional and social clubs formed, their members all hoping to make a name for the young city and attract new investments. One such organization, the Flambeau Club, began holding parades to attract attention to downtown businesses.

Later, inspired by Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans and the Veiled Prophet parade and ball in St. Louis, the Flambeaus decided Kansas City needed its own carnival season. In September 1886, a parade association formed to plan a multi-day festival the following year.

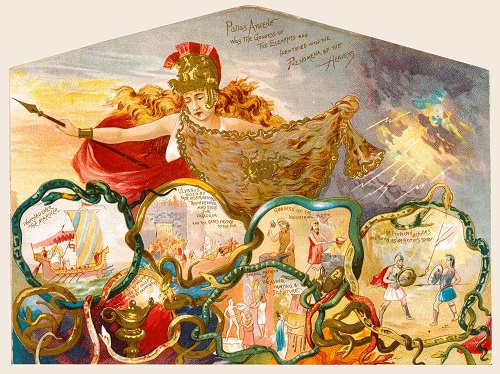

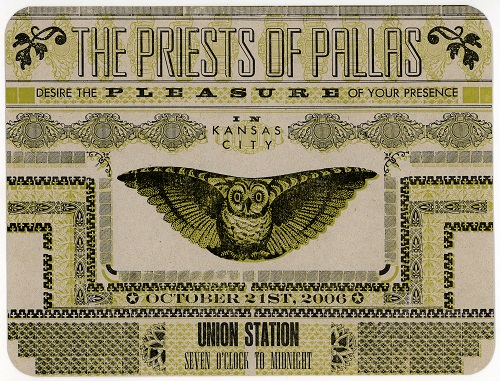

Organizers chose Pallas Athene, the daughter of Zeus and goddess of science, the arts, and protector of cities as the festival’s patron. According to Greek mythology, she appears dressed in bright armor accompanied by an owl and a snake, both symbols of wisdom. Her “priests” promised that she would watch over the young city so long as Kansas Citians paid homage to her once a year.

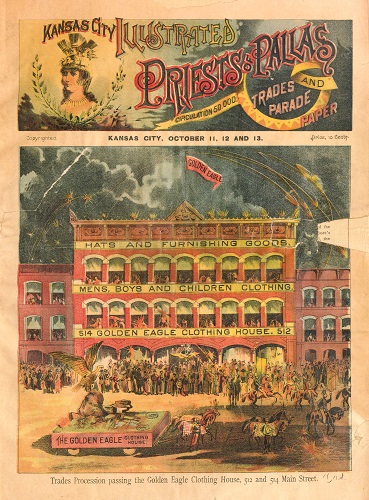

The city had landed the National Agricultural Exposition, a 45-day convention scheduled to begin September 15, 1887. To prepare, the Commercial Club, the forerunner of the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce, assumed control of the POP and scheduled three parades and a gala ball for October 11-13.

The October 13 parade was a hit. So many onlookers crowded the route that the police had to ride ahead to clear a path.

In the festival’s early years, the part of Athene was played by a man from the Commercial Club sporting a blonde wig — organizers assumed riding in the parade would be too much for a woman to bear. Horse-drawn floats depicting scenes from Greek mythology, world history, and fairy tales departed Seventh Street and Broadway Boulevard and snaked along Grand Avenue and Main Street between Third and 19th streets.

In town for the exposition, President Grover Cleveland and first lady Frances Cleveland watched from the Coates House Hotel.

In subsequent years, schools went on holiday so local children could attend.

Earlier that month, about 1,000 members of the city’s social elite received invitations to the POP ball from a mysterious figure identified only as “Jackson” — more on that coming up. Starting at midnight after the parade, ball invitees arrived at a warehouse at Seventh Street and Lydia Avenue that served as the festival’s headquarters. In 1899, the ball moved to the new Convention Hall.

Initially, the POP did not conflict with St. Louis’ Veiled Prophet celebration. In 1889, it was scheduled during the same week. Organizers assumed farmers in central Missouri would choose wisely and head west when it came time to bring their crops to market and enjoy a little fall frivolity.

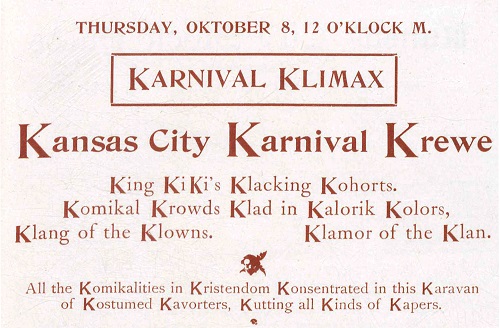

The grand POP parade and flower parade remained popular, but in 1894, the Kansas City Karnival Krewe (the KKK encountered by our reader) added another. The group of businesspeople and downtown merchants encouraged attendees to wear costumes and unleash “the pent-up humor of a year.” Before each festival, the group selected a new King Ki Ki (another KKK) to lead the parade. The police turned a blind eye so long as the public revelry remained “strictly decent and safe.”

Evidence establishing a direct link between the POP and the Ku Klux Klan was not found in available research material. It is possible that the use of the KKK abbreviation was an unfortunate coincidence. The festival was created to mimic Mardi Gras, so it is also possible the name was adopted to align the festival with the wave of performative violence and racial subjugation perpetuated by Klan chapters in the American south following the Civil War.

In her 2017 book, “The Second Coming of the KKK,” historian Linda Gordan lists six factors at work in American society of the late-19th and early-20th centuries that drove a surge in Klan activity in the 1920s: racism, anti-immigrant sentiment, the temperance movement, Christian evangelicalism, populism, and the popularity of fraternal organizations. All were certainly at work in 1880s Kansas City, and notably, fraternal organizations and mutual benefit societies that prided themselves on secrecy and arcane rituals were directly involved with organizing and producing the POP.

Overt racism was also on full display during the early POP festivals.

Some parade participants wore stereotypical ethnic costumes and blackface makeup to impersonate people of color. One float in the 1899 parade had the theme “All Coons Look Alike” and featured ragtime musicians playing in a watermelon patch.

Years later, it became known that the mysterious “Jackson,” sender of the festival’s ball invitations, had been Charles A. Jackson, the Commercial Club’s longtime Black porter. Whether or not this was an inside joke at the man’s expense is not known. However, the motives driving the use of a Black employee’s name to send exclusive ball invitations to the city’s moneyed social elite is suspicious.

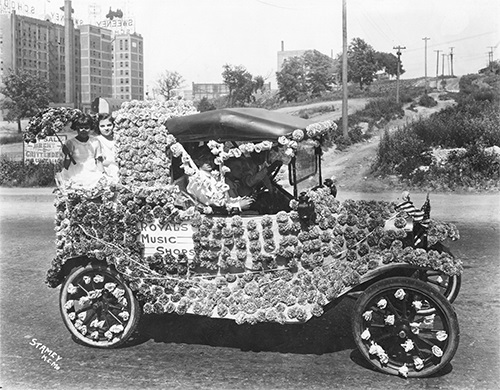

Most parade floats over the years were decorated in patriotic, mythological, and other fantastical themes. Photographs, postcards, and other souvenirs that capture them make the POP a source of nostalgia for many. Complicating this legacy, however, is that while Kansas Citians of color could watch the parades and were certainly welcome to spend their money at downtown businesses, their representation in the festivities was mocking and driven by the racist humor of the day.

Previously only lit by torch and pulled by horses, the Metropolitan Street Railway Company made its streetcar tracks available to POP parade floats in 1902. Not only could floats elegantly glide along the electrified tracks, they also could draw power for decorative lights. Organizers were also given access to a company owned warehouse to use as headquarters.

The upgraded streetcar parade held until 1912. The city’s transit company was bankrupt, and its court- appointed receiver ended the complimentary use of its streetcar tracks and warehouse for festival purposes. No parades happened that year.

The 1912 ball took place in the same week as the American Royal’s livestock show, another annual fall tradition first held in 1899. With no parade, the POP could not compete with the American Royal’s growing popularity. The 1912 ball would be the last POP event for nine years.

The POP parade and ball returned in 1922. However, content with the fall American Royal events, the public did not respond. Organizers held the revived festival in 1923 and ’24 but announced it would not return the following year. The festival’s assets were liquidated to compensate investors and, in 1928, the remaining POP parade floats were sold for scrap.

After 1924, the POP sat idle for decades. In 2005, inspired by the Crossroads-fueled downtown renaissance, the Jackson County and Westport historical societies brought it back as a fundraiser. There was no parade this time, but anyone who paid the price of admission received an invitation to a private ball at Union Station.

The final POP ball took place on October 26, 2007. While the festival’s iconography and illustrations of lavishly decorated parade floats are a source of wonder for some, our storied carnival celebration was not welcoming to all Kansas Citians and consequently presents a complicated legacy for the city. Whether or not the POP can return to restore the blessings of Pallas Athene remains to be seen.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.