Central Library has a new parking validation process.

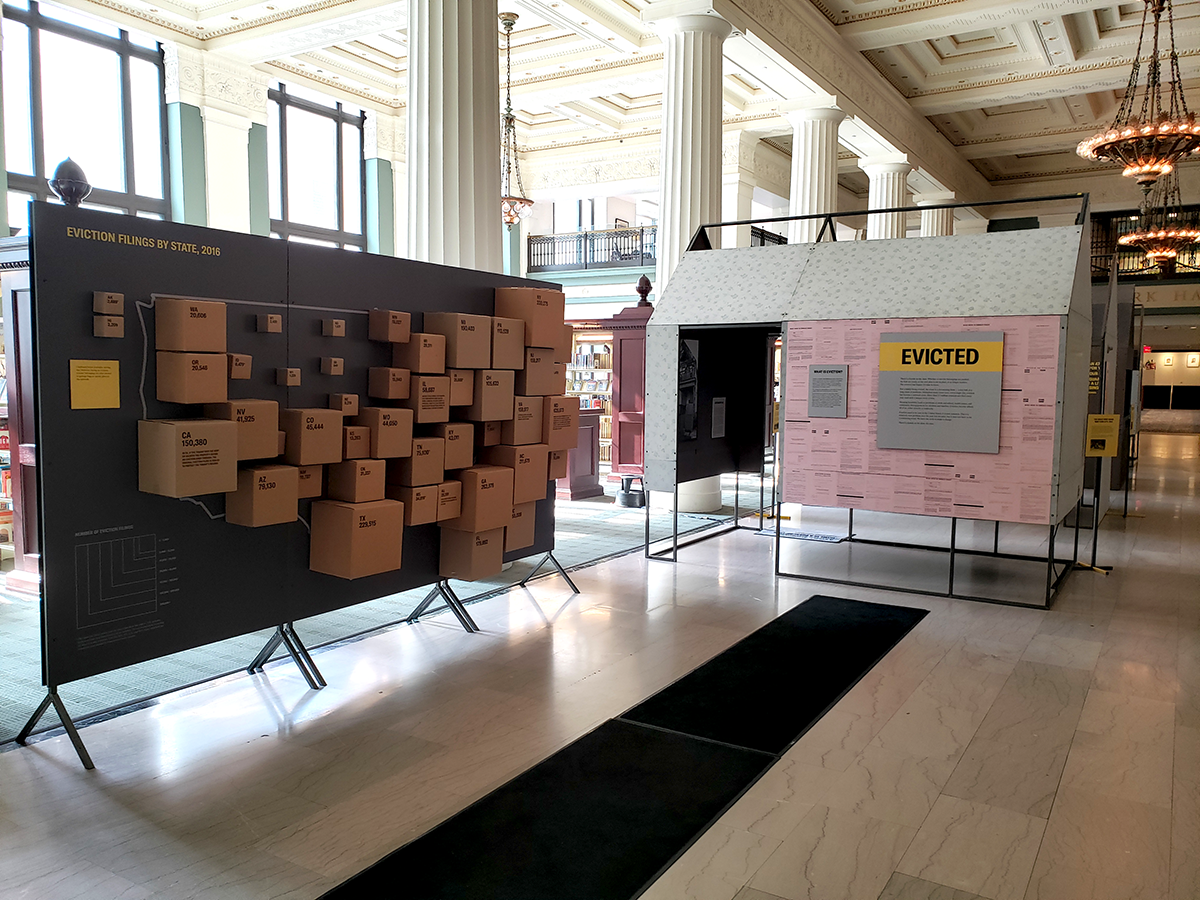

In the grand hall of the Kansas City Public Library's downtown Central Library sits a row of four small houses. They’re shaped and positioned like Monopoly pieces but are tall enough for visitors to walk through.

Each wallpapered structure reveals information about the nation’s housing crisis — the eviction crisis, in particular.

The free, temporary exhibition, there through July 17, is called Evicted and is based on Matthew Desmond’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (Crown Publishers, 2016).

Evicted

On display through Sunday, July 17, 2022

Central Library, 14 W. 10th Street, KCMO | Kirk Hall

Details >

A curator at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., hit on the idea of translating Desmond’s book into a display in 2017, and it showed there the following year. Response was strong, and a national tour began in 2019. Kansas City is the seventh host city of an eventual 10, which will end in February.

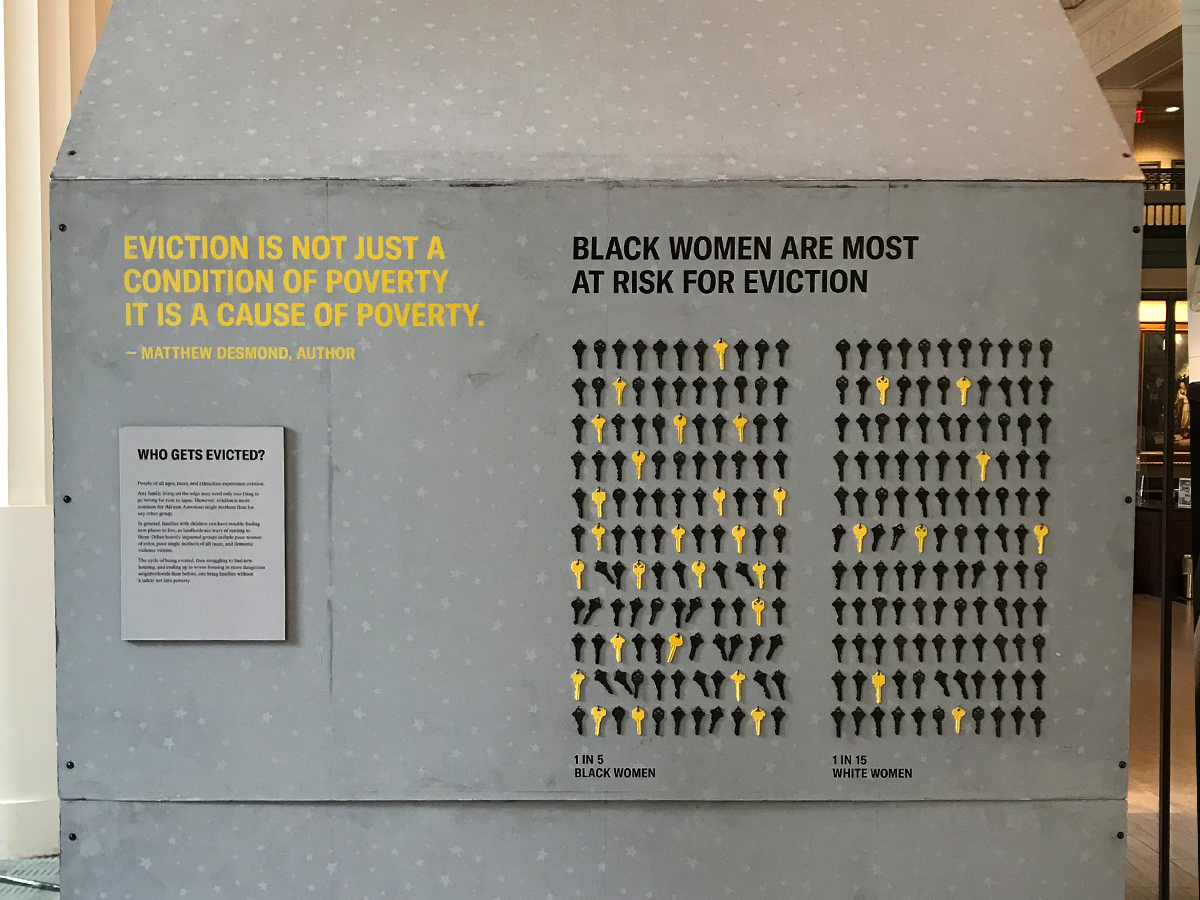

Cathy Frankel, the museum’s vice president for exhibitions and collections, says one of the goals was to dispel myths surrounding evictions, like that the majority are the result of people who won’t work and subsequently can’t pay rent.

“We really wanted to be able to tell those stories in some three-dimensional way with statistics behind it,” Frankel says, “so people walk out understanding what is happening with this eviction crisis, and how we could all get involved and make a difference.”

A welcome mat at the entrance of another house reads: “A stable, affordable home is a prescription for good health.”

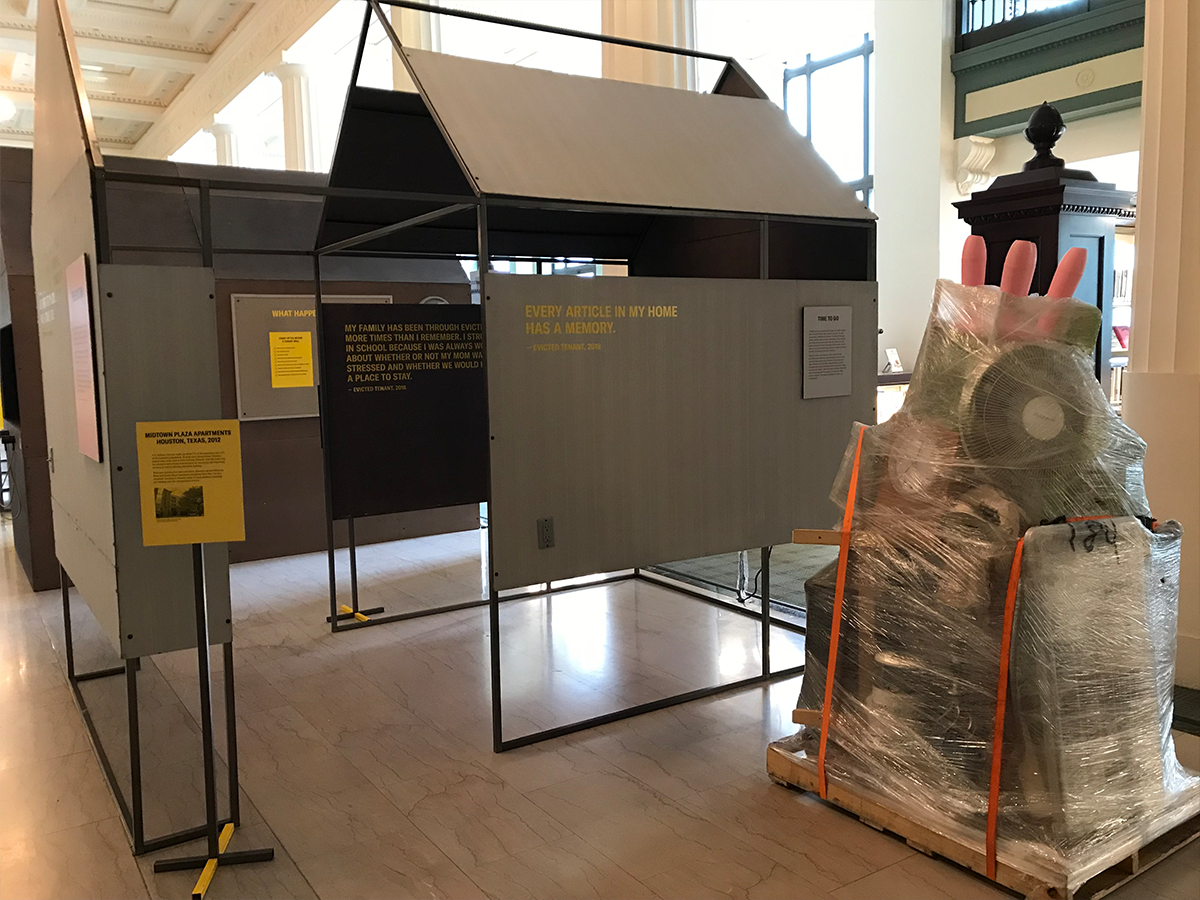

A fully packed moving pallet provides a full stop to the exhibition. It’s parked at the end of the row as if movers had hastily entered a house and unceremoniously thrown a tenant’s belongings in a pile to take to storage.

Desmond, who worked on the exhibition with the National Building Museum, says that in some cities, renters who’ve been served a formal eviction notice have a choice: curb or truck. Choosing “curb” means that movers place a family’s household goods by the street.

The selection of “truck,” favored during inclement weather or when someone doesn’t have a moving van, means that everything in the house is wrapped up on pallets and shipped to a bonded storage facility for a set amount of time, after which it’s hauled to a landfill if no one pays to claim it.

The objects on the pallet at the touring exhibition mimic those he saw conducting research for the book in Milwaukee.

“You would just go into the warehouse and there was just crate after crate after crate of these things. People’s belongings, you know, wrapped in cellophane and you see a lot of kids’ stuff, you know, you see a lot of just the regular detritus of life,” Desmond says.

At the Library, what sticks out are an electric fan, a battery-operated wall clock and pink, plastic child’s stool.

“We got foreclosed before it was all the rage,” he quips. “And I remember going through that and feeling very ashamed, and I blamed my father. I think that over the years, I’ve come to ask something like: Why is this the way the country treats families that fall on hard times?”

He was in favor of an exhibit version of his research for several reasons. For one, young students are unlikely to read his book, but many have been evicted themselves or know someone who has been, and this exhibition is a way to reach them, either to educate or to reduce some of the shame that he remembers so acutely.

But then there’s the sensory component that drives home the information.

Evicted in exhibition form involves videos of an eviction courtroom that people can see and hear, the doormat with the message on it that a visitor can feel underfoot, and numerous touchable objects that just don’t exist in a book — even the feeling of having a roof overhead.

“There’s a real emotional punch that the exhibit brings, and I’m incredibly grateful for that. … I think that going through a hard thing by yourself feels like a personal problem, and sometimes it can feel like a personal failure,” Desmond says.

Tara Raghuveer, founding director of the advocacy group KC Tenants, says the roughly 42 renters a day in Kansas City who receive formal eviction notices don’t even have the “curb or truck” option referenced in the exhibition.

She says that a few years ago rules changed in Kansas City proper. “If you haven’t moved by the time the (court deputy sheriff) has deployed to come to your house, they just change the locks, and your (stuff) is locked inside.” Raghuveer pauses.

“There’s no ‘and then,’” she says, meaning that’s the end of the story. Everything that family owns becomes inaccessible and, for all intents and purposes, is gone.

That’s exactly what happened to Patrina Dixon, who’s now visited the exhibition at the Library three times, and every time she says she feels angrier.

Dixon works at the Center for Developmental Disabilities. Both she and her 16-year-old son are on the autism spectrum. Though they had lived in the house for over two years, in under 48 hours they were locked out and homeless, despite a preemptive call to the sheriff’s office on her part.

“We couldn’t figure out why. I only owed maybe like $3,000,” Dixon says. “I could have paid that had I had the time.”

She says that the landlord wouldn’t renew her lease, citing “difficulty with communication.”

From the time the landlord notified her that they needed to move in April until now, she’s tried to help herself using the appropriate channels.

She filled out the State Assistance for Housing Relief (SAFHR) form. She had assistance, but the form was kicked back for an error, causing further delay.

Adding to the problem is a backlog of thousands of applications like hers awaiting processing, says Beth Hill, the Kansas City Public Library’s community resource senior specialist.

Raghuveer, a Kansas City native who met Desmond while she was a student at Harvard University and contributed research to his book, says, “The concept of the exhibit is great, but it can’t just stop with staring at numbers and understanding the problem.”

“There’s also an obligation that we have to listen to those who have been impacted and follow their leadership toward the solutions they prescribe,” she adds.

The Library system has just begun a pilot program at the Lucile H. Bluford Branch with University Health in which trained peer specialists who’ve experienced homelessness and other trials are standing by to assist patrons who need help.

The stories Hill hears from patrons in crisis add as many dimensions to the challenges of eviction as the exhibition itself; problems no one thinks of unless someone who’s gone through the ordeal explains.

Many tell about losing not only their belongings, but also identification documents — Dixon lost her birth certificate — through eviction or through the theft that she says is rampant in the camps and at the few shelters that are available to the unhoused.

“A lot of our patrons don’t have birth certificates anymore. They go to sleep, and somebody comes along and picks up everything they’ve got. And then they’ve got to start all over again,” Hill says.

Without identification, Hill says, “They essentially become an alien. I mean, they don’t exist anymore, because they have no paperwork. And so they have to start that process all over again.”

Shelter is a basic need, but the exhibition highlights that a place to live is more crucial to a human being’s success than simply staying warm and dry. This critical beyond-basic factor is the piece that often goes unremarked on in discussions of the crisis.

“As Matt Desmond always says, people talk about education being what people need to get out of poverty,” Frankel says, “which really, if you don’t have a steady home, it’s impossible to get that education to get yourself out.”

She says the house-like nature of the exhibition, with its welcome mat and use of wallpaper, will remind visitors how important home is to them personally.

And if it works? When the exhibition was home at the National Building Museum, people pulled out their checkbooks.

In Kansas City, Hill hopes people will at the very least understand that Homelessness Is a Housing Problem — referencing the name of a book by Gregg Colburn and Clayton Aldern — rather than a personal shortcoming.

She also wants to see people moved enough to not only speak up to their representatives but get involved searching for creative solutions that would give Kansas City more transitional housing that would allow the houseless to get back on track.

For instance, she says Kansas City’s charitable foundations have a collective endowment of $683 million, according to GrowYourGiving.org. She suggests that taking 10% of that amount to rehab a couple of defunct downtown hotels would give many of Kansas City’s 1,800 homeless people transitional housing.

But until then, a number of resources are available to those looking for assistance. As of June 1, a Kansas City ordinance guarantees a lawyer to anyone threatened with eviction. Kansas City is the 13th city in the U.S. to pass a law guaranteeing legal representation to tenants facing eviction.

This story, written by the Library's Anne Kniggendorf, originally appeared in The Kansas City Star.

RESOURCES

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City

Matthew Desmond

Find in our catalog

Listen to a recording from Matthew Desmond's 2016 presentation at the Central Library.

Audio | Event Details

Kansas City now offers a right to counsel for those threatened with eviction. Call 816-474-5112 or visit kcmo.gov/city-hall/housing/tenant-resources

KCMO Tenant Resources

www.kcmo.gov/city-hall/housing/tenant-resources

Tiffany Drummer – Tenant Advocate: (816) 513-3026

Nicole Woods – Tenant Advocate: (816) 513-3046

Legal Aid of Western Missouri

4001 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd #300, Kansas City, MO 64130

M-F: 8:30 a.m - 5 p.m.

(816) 474-6750

Heartland Center for Jobs and Freedom

4044 Central St., Kansas City, MO 64111

M-F: 9 a.m. - 5 p.m.

(816) 278-1092

KC Tenants

Hotline: (816) 533-5435

www.kctenants.org