From Oops to Ahh: Return is 61 Years Late, but Library Is Fine-Free

Considering the level of his Library infraction, David Izzard’s response to what he’d done – or forgotten to do – was mild. When he ran across two overdue vinyl record albums he’d checked out more than six decades ago, then neglected to return, he said, “Oops.”

“Last winter, I decided I was going to redo my office in my home,” Izzard says. During the redo, his intention was to catalog all his music. “And that’s when I discovered them.”

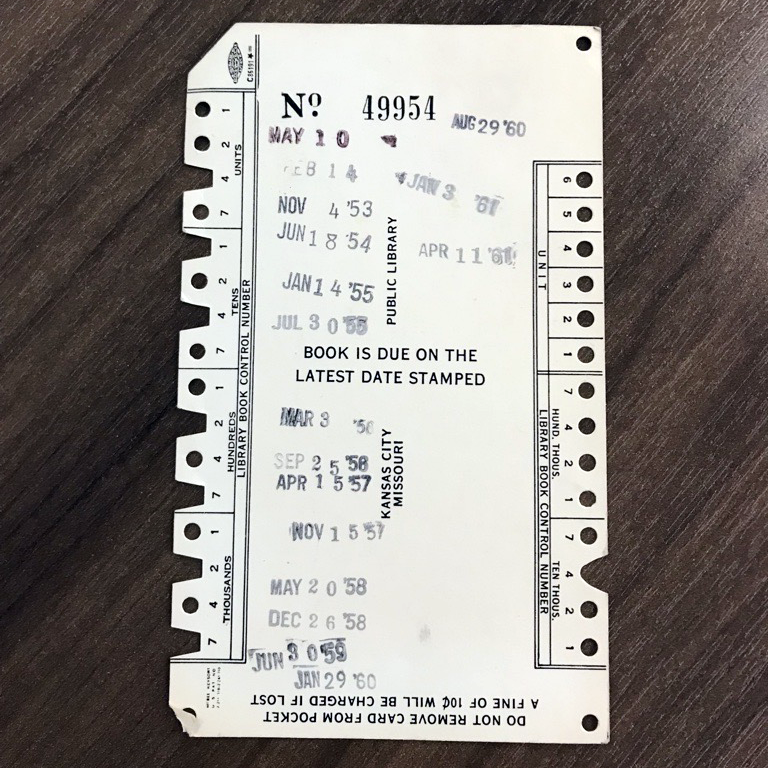

He confesses that his first thought was, “What difference does it make?... And then I opened them up and saw that the card was still in there.”

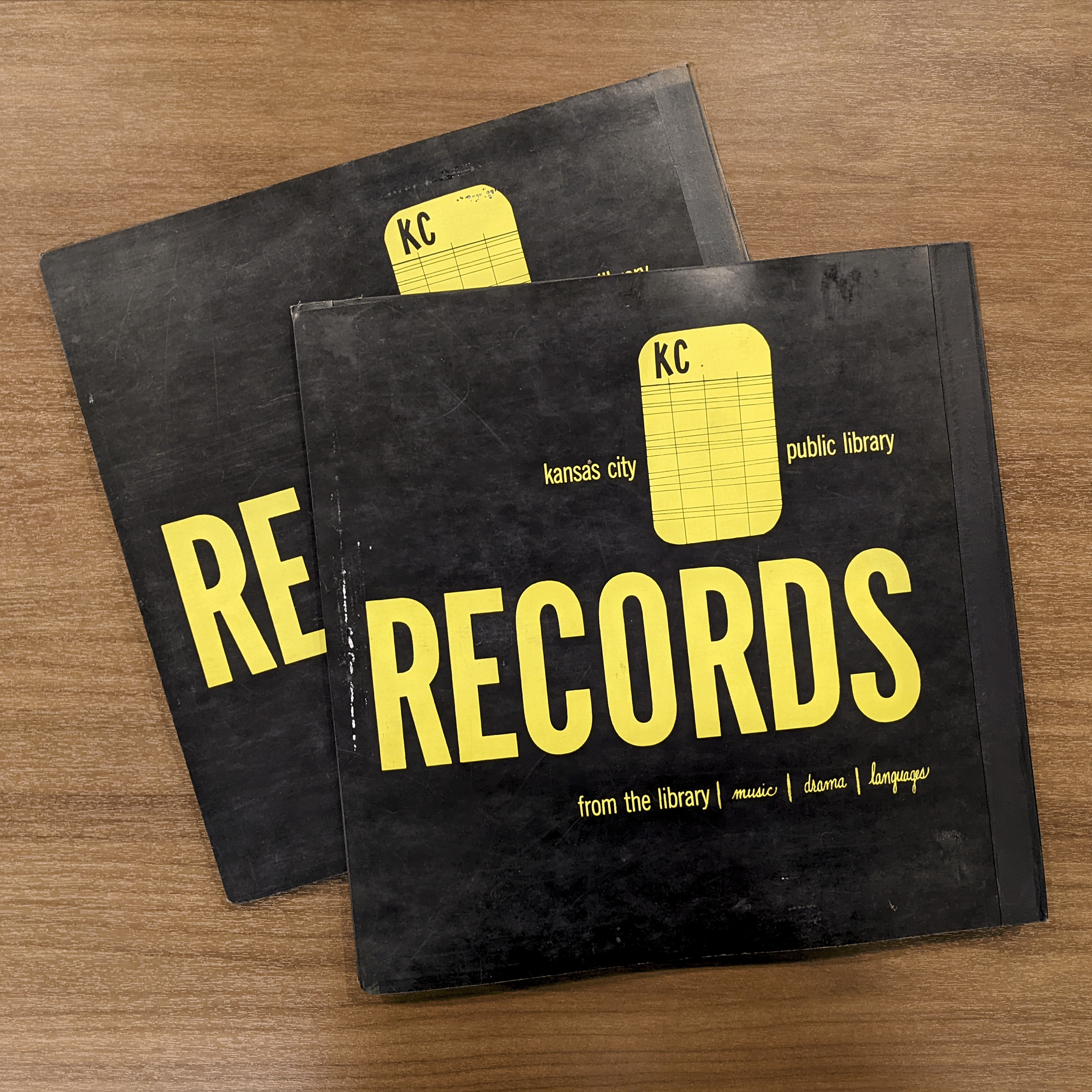

Those records, The Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet’s recordings of Barber: Summer Music Op. 31 and Nielsen’s Quintet for Winds Op. 43, and Béla Bartók’s excerpts from Mikrokosmos, were due back to the Library on April 11, 1961.

Oops, indeed. A chastened Izzard finally returned them to the Library in early spring.

The late fine for Library materials in 1961 was 2 cents per day. In 1962, that increased to 5 cents. Izzard said his second thought after “oops” was, “I’m going to have to buy the library in order to pay the fine.”

But the Kansas City Public Library doesn’t roll that way – at least not these days.

In 2019, the Library implemented its Freedom From Fines Policy. Research and experience from libraries across the nation show that fines deter people from using libraries, either because they fear incurring them or because they owe fines they are unable to pay.

Lucky for Izzard.

Merritt Tressler, Central Library’s delivery services senior assistant, received the patron’s tardy package in early April.

“At first, I was very confused since the box looked like it was coming from a record company,” Tressler recalls. For safe shipping, Izzard had recycled packaging from a company that had recently shipped records to his home.

Then Tressler read Izzard’s letter of apology and understood. Izzard was offering to replace the items with modern vinyl or CDs or buy any other music for the Library’s collection. Tressler says, “I was very touched by his generosity and consideration.”

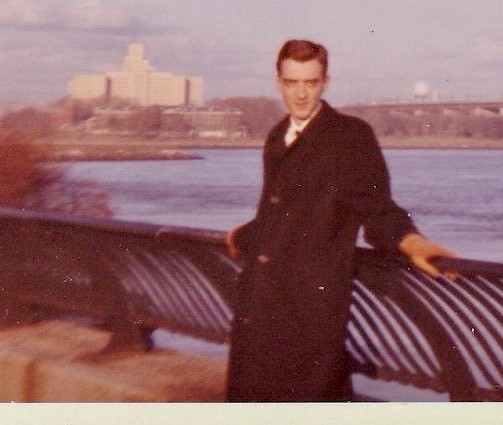

Izzard says that in 1961 he was not so considerate, just an “irresponsible young kid with no common sense.” He’d checked out the records, probably to complete some homework, from the then-new Main Library at 12th and McGee streets, replaced by the current Central Library a few blocks away in 2004. The Library had begun lending records to patrons 10 years prior to Izzard’s visit.

On the day he checked out the music, Izzard was a sophomore at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, which at that time was simply the University of Kansas City. He studied in the Kansas City Conservatory of Music – an organization that had joined the university two years earlier – and graduated with a degree in theory and composition.

In many ways, he was the ideal custodian of the two albums. His personal CD collection runs into the thousands; his record collection isn’t as large, but it contains rare recordings as well as some that are broadcast quality.

Upon his death, all his music will go to the Marr Sound Archive at UMKC’s Miller Nichols Library.

Music has been Izzard’s whole life. In the early 1970s, he carved out a career in Kansas City working on jingles for just about every car dealer and bank in the area. But he wanted more, which is what was behind his packing up the records and leaving town.

“I like to say I was a whale in a pond. So, I moved where I could be a whale in an ocean and wound up as a minnow in an ocean,” Izzard says by phone from his home in Leawood.

He took the Library’s vinyl with him to California, first to Santa Monica and then the San Fernando Valley in North Hills. The records sat idle while he made a decades-long career as a copyist in Hollywood, working as part of a team on scores for movies like Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Titanic, and Die Hard and hundreds of television shows. For 15 or 16 years, Izzard was on the team that handled the music for the Academy Awards as well.

He was one of roughly 100 copyists in Los Angeles, mostly before computers were up to the task of creating sheet music for musicians. He and his coworkers would receive a score from someone – for instance, composer John Williams, who, Izzard says, wrote a score “so clean you could eat breakfast off of it” – and then write out the music for each instrument involved.

He says complicated music for a big movie like Indiana Jones might take a team of two dozen copyists two weeks to finish, whereas one copyist was able to complete an entire season of the TV show Frasier in one day.

Izzard retired in 2006 and moved the Library’s albums back to the Kansas City metro area in 2013. Today, he's working on his own projects, including a new release of big band music he composed, arranged, and produced.

Vinyl was gradually phased out of the Library’s collection, beginning in the early 1980s. Still, the staff appreciates the gesture of returning the records.

“We’re always happy to see lost items come back to us,” says Nash High, who works with Tressler as a materials receiving specialist. “On our end, the records are exciting as sort of a time capsule – a rare chance to peek into Kansas City Public Library from the 1960s.”