Central Library has a new parking validation process.

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Kynala Phillips | Kansas City Star

Editor’s note: This story is part of our Black History Month KCQ series and was fueled by questions from students in Kansas City area Black Student Unions. Students at North Kansas City High School asked about what role high school students played in the civil rights movement in KC. These walkouts after MLK’s assasination are just one example of student activism in our city, which continues today.

It was Monday, April 9, 1968—the day before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral. King was assassinated in Memphis four days earlier, and the weight of his death could be felt across the country.

Harry Ross was a student at Manual High School in Kansas City at the time. In an interview in 1969, he talked about how grief rippled through the halls in the days following Dr. King’s death.

“It was like this—we had just talked at school, you know about how it happened, feeling bad about how it happened,” Ross said in the interview.

The students had talked about wanting to do something to recognize Dr. King on the day of his funeral.

“And some of the kids said, you know, we should walk out the next day,” Ross said in the 1969 interview. “It was really something that happened all of a sudden…I was just expressing my feelings and so were many others.”

What began as Ross and other students expressing themselves at school would soon turn into a wave of protests across the city that would become one of Kansas City’s most significant uprisings.

The decision to call off school

Across state lines, students in Kansas City, Kansas, were to have the day of Dr. King’s funeral off school to mourn, but not on the Missouri side.

Kansas City school officials considered closing schools, but decided against it.

“The three black folks voted to say we should not open the schools,” said Alvin Brooks, who was the coordinator of school, parent and community relations with Kansas City Public Schools in 1968 and talked with The Star this week.

Instead, KCPS Superintendent James Hazlett elected to keep schools open.

“Our kids are going to feel that you don't care enough about Dr. King as others do. They're going to be marching out, and we’re going to have some trouble,” Brooks said of the decision.

Walking Out

Like Brooks predicted, students like Ross and some of his fellow classmates made the decision to walk out of school in protest.

“We all assembled in front of the school building, and it was just a few of us, and we called ourselves the Young People's Association,” Ross said in the 1969 interview.

Students at Lincoln High School, now called Lincoln College Preparatory School, had already started marching.

Ross said he became a de facto leader of the group marching from Manual, and he led his peers to link up with students from Lincoln.

The two schools then marched peacefully to Central High School to join more students before heading downtown. Once they arrived at Central High, things became a bit more tense.

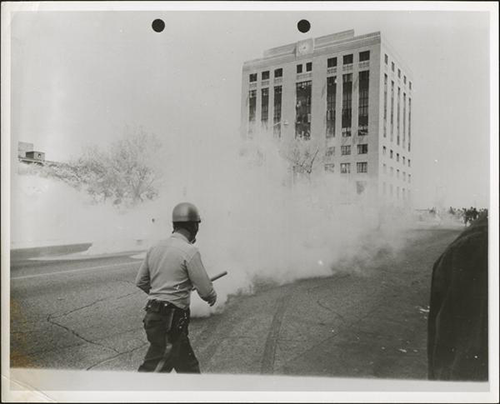

In the 1969 interview, Ross said he didn’t see students acting out of turn, but he heard reports of people turning over cars, cops throwing tear gas into cars and kids throwing rocks.

Ross soon noticed police officers following him and other students once he reached 31st and Woodland.

“They started throwing tear gas at everybody that was in the crowd,” Ross said. “They didn’t want nobody to be overpowering them because of Martin Luther King.”

Riot gear in Parade Park

Brooks, who voted to close schools, was attending a memorial service for Dr. King that Tuesday when he received an emergency call from the assistant superintendent of KCPS, Bob Wheeler. Wheeler told him that students were marching in protest, and police had tear gassed one group near 31st.

“We told those folks last night that this is going to happen,” Brooks said to Wheeler on the phone before heading to his car to meet other city leaders and students near 27th and Vine.

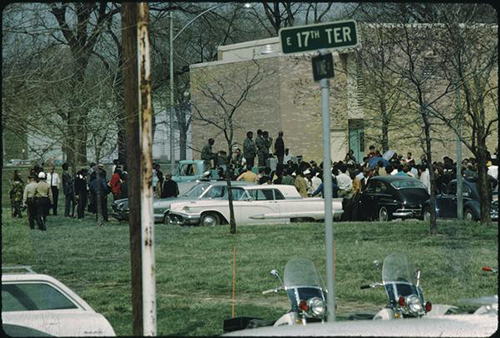

The students made it clear that they wanted to go to City Hall for a rally.

Instead of waiting for the students to get there, Kansas City Mayor Ilus Davis met up with the students and joined them in their march.

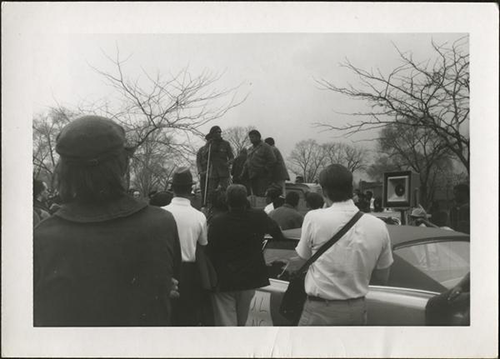

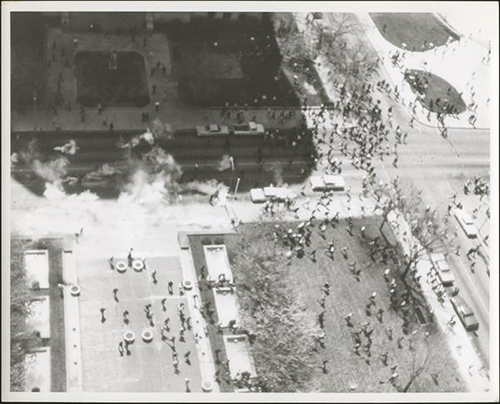

As the group including the mayor, Brooks, students and other community members approached Truman road near Parade Park, police dressed in tactical gear blocked their way.

“We [looked] up and we saw two buses full of policemen–the riot squad and they were lined all up in a row, going to block the way,” Ross said in the 1969 interview.

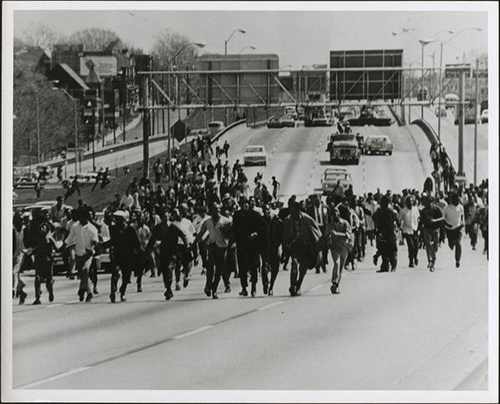

Brooks said that police ushered the mayor away from the scene, and the students continued their march on I-70 towards city hall.

“The riot squad was trying to stop them, but the mayor told them to let them go ahead,” Ross said in 1969.

Once at city hall, city leaders, including Brooks, Mayor Davis and leaders of the Kansas City Chapter of the Black Panther Party, spoke to the congregation that had gathered.

As the speeches kept flowing, the tensions between the crowd and the police ran high. At one point, someone flung a soda bottle past a barricade of police, and officers started “to gas, beat and arrest students and community members,” according to a historical sketch of events by the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Tear gas at Holy Name

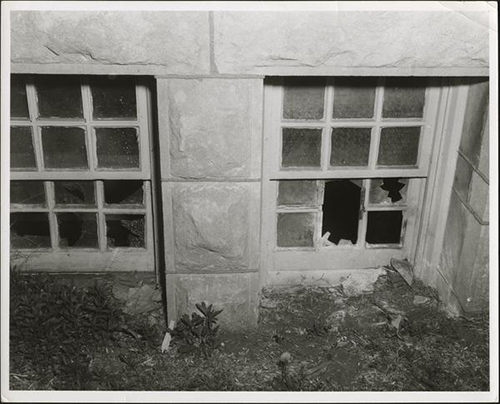

Brooks said community leaders in the crowd, including KPRS-FM radio personality John Fraizer, organized for students to go to Holy Name Church for a dance so students could regroup and have somewhere safe to be.

Once students got to the church, the police still saw the kids as a threat.

“We were supposed to be having a dance, and the cops threw tear gas through the windows for no reason at all,” one student told an interviewer in 1969.

“Just threw it through the windows. You know the police don’t open no doors, they kick them in,” another student said in the 1969 interview.

Brooks said he went inside the church to assess the damage.

“I went inside and saw five canisters of gas, and the kids who were coming were all out there coughing and everything. And so that night is when the riot started,” Brooks said.

Days of unrest, and six Black lives lost

After that day, the unrest escalated and went on for nearly four days.

While often referred to as the 1968 Kansas City riots, reporter Lena Rivers Smith, a Black woman who was present and reporting on the events at the time, referred to the days as civil disorder.

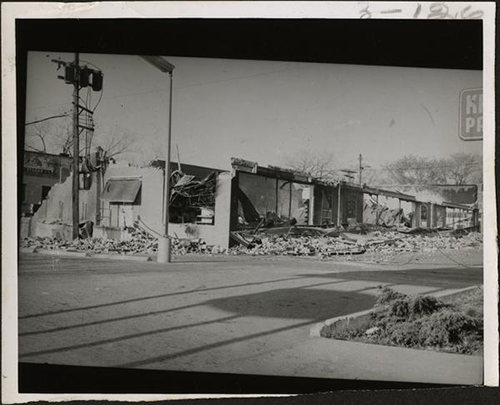

“Burning and looting took place up until I think that Thursday. In the end, six Black men were killed,” Brooks said. “Race relations between the Black and white were widened and many of the white-owned stores were burned in the Black community.”

Six Black people were killed, at least five of them by police. Another 78 people were injured, and there was $4 million dollars worth of damage in the city, according to the Kansas City Public Library.

storefront to the ground. | LaBudde Special Collections, UMKC Library

Around 300 people were arrested in total, and the average age was between 17 and 24, Historian Joel Rhodes explained during a 50th anniversary panel about the uprising.

Then What?

Later that year after the violent police response to the student-led walkouts and the burning and disorder that followed, Mayor Davis created a city commission on civil disorder.

Brooks, who joined the students marching, said he was interviewed as part of the process.

This special commission created a report in August 1968 that looked back at what happened earlier that spring and recommended next steps for Kansas City.

Brooks said the report failed to mention that six Black men were killed, but otherwise did what he thought was a good job of detailing what changes needed to be made in the city.

Some of the recommendations included giving Kansas City local control of its own police department, which was and still is overseen by a board of commissioners appointed by the state. This lack of local control allowed the state instead of the city to decide how to direct police response to the protests in 1968, and it prevents the city from having full control of its police budget today.

The report also called for the city to improve the quality and availability of housing, a plan to improve trash pickup and recommendations for how to better maintain city neighborhoods.

All of those are still issues in Kansas City today.

“From local control of the police department, economic development, aggressive movement for race relations, working with the schools, desegregation,” Brooks said. “None of those issues have been dealt with.”

As recently as this week, students in the Kansas City metro protested incidents of racism in their schools, and in the past couple years, groups have led protests around issues with policing and housing.

“This riot really surprised everybody in Kansas City because they thought the negroes here in Kansas City didn’t have that much sense,” Ross said. ”That’s what them kids felt good about, because they was trying to show them that they had rights themselves.”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.