KCQ: How one Kansas City company helped carry America through World War II

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Randy Mason | The Kansas City Star

War stories most often celebrate heroism, courage and grace under fire.

This week “What’s Your KCQ?” highlights a war story filled with ingenuity and perseverance as well.

It starts with a question from reader Linda Pearson. She remembers walking by the Darby Corporation offices on 6th Street in Kansas City, Kansas when she was “school age.”

She asked KCQ, “What role did the company play in America’s war effort?”

Today the signs that once caught Linda’s attention are long gone. In fact, the only evidence of something nearby named Darby are a handful of markers along Interstate 635. The ones that proclaim it the Harry Darby Memorial Highway.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. First a little backstory.

Harry Darby, Jr., was a Kansas City, Kansas, kid from the start, born on Strawberry Hill in 1895. His father, Harry Darby, Sr., owned the Missouri Boiler Works Company in the West Bottoms.

The boiler works later moved to 3rd and Armstrong on the Kansas side.

Young Harry started working at the factory in his teens, then headed off to study mechanical engineering at the University of Illinois. After graduation in 1917, he joined the army, and soon saw combat in World War I, not unlike a fellow Kansan he befriended, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

We’ll get back to that too.

After his father’s death in 1923, Darby secured a loan to buy the company from the bank. The budding industrialist renamed it Darby Steel. Business flourished at first--until the Great Depression forced him to lay off half his workers.

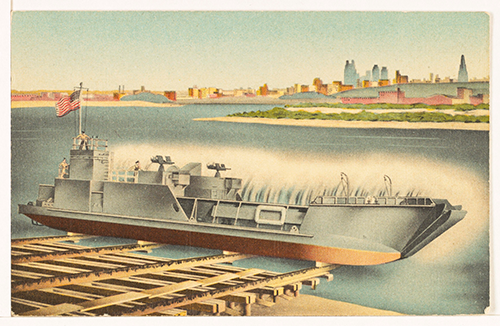

to the beaches of Normandy during World War II. | Wyandotte County Historical Society

In 1938, after a stint on the Kansas Highway Commission, he forged a deal for the bankrupt Kaw Steel Construction Company. He called his new venture the Darby Corporation. According to the Kansas Business Hall of Fame, it soon became one of the largest manufacturers of steel plates in the nation.

With another war looming on the horizon, defense officials needed to rebuild the country’s industrial might.

The Midwest saw an opportunity. A brochure issued by the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce touted a ready pool of industrious workers, including “farm boys with their farm machinery experience.”

Soon the Pratt & Whitney engine factory on Bannister Road and the Lake City Ammunition Plant near Independence were humming with wartime production. So was the Fairfax Industrial District near the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers.

From 1940 to 1945, over 6,000 Mitchell B-25 bombers rolled off the assembly line at North American Aviation in Fairfax. Nearby at Kaw Point, workers at the Darby Corporation shaped steel into locomotives, rail cars and casings for large bombs.

But those men and women also churned out something equally vital to the cause. Something you might not expect.

LCTs and LCMs-- amphibious landing craft which the Navy used to transport tanks and troops from ship to shore.

The Darby Shipyards were spacious enough to hold as many as a dozen of these landing crafts at a time in various stages of construction.

These “prairie ships” then slipped into the Kansas River from a ramp where Kaw Point Park is today. From there they went on to the Missouri, into the Mississippi, and eventually all the way to New Orleans.

It wasn’t just a handful of them either. At the rate of one a day for four years, 1,400 of the sturdy steel workhorses left Wyandotte County for use in military operations halfway across the world.

While the heartland has never been a maritime hub, the system worked surprisingly well, at least until early 1944. In the book “City of the Future,” authors Harry Haskell and Richard Fowler recounted a story from Harry Darby.

That winter, he told them, levels on the Missouri River dipped too low for the landing craft to safely journey south. A large queue began to grow.

Authorities ordered the release of water from a dam upriver in hopes of raising the levels here, but the results were negligible.

So, engineers decided to put the LCTs on wheels and drive them to the Gulf.

Because of their width, overpasses and bridgework along the route would have to be reconfigured, at least temporarily.

Though such a plan would have been incredibly costly and disruptive, orders came down to proceed.

But, a last-minute rain saved the day. According to Darby’s story, water levels rose just enough on January 21, 1944, to slide a line of boats like LCT-856 into the Kaw.

Less than five months later, that same “prairie ship” was among the Allied forces storming the beaches at Normandy. Hundreds more landing crafts built in Kansas City brought the battle to other parts of Europe and the Pacific.

The government bestowed E-Flags on the company for its excellent work on the home front. But Darby deflected much of the personal credit.

“It was done by the men who work with the tools,” he told Fowler in another magazine article, “to prove they could do an industrial job out here in the West. I’m proud of them.”

After the war, the Darby Corporation changed gears. An ad in The Kansas City Star in December 1945 touted products like water towers and railroad supplies for “speeding reconversion and winning the peace.”

It wasn’t long before Harry Darby had a new title: U.S. Senator.

Portrait of Harry Darby, Jr., in 1949 when he entered the U.S. Senate. | Wyandotte County Historical Society

In December 1949, Kansas Governor Frank Carlson appointed him to fill the seat left vacant by the death of Clyde Reed.

After 10 months in office, Darby chose not to run for re-election. But he continued to play a significant role in Republican politics, state and national.

Remember that longtime friendship with Ike?

Darby’s counsel and political savvy was a potent part of Eisenhower’s 1952 presidential campaign.

A decade later, Darby led the effort to raise funds for the Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum. He also commissioned the Eisenhower statue that stands prominently on the grounds in Abilene.

Ironically, this industrialist loved nothing more than tending the land. Darby owned a large farm near Edwardsville, and actively participated in most aspects of its operation.

He championed the American Royal and helped launch the Agricultural Hall of Fame. Farming, he maintained, was still the bedrock of the region’s economy.

Darby died in 1987 at Bethany Hospital--less than a mile from his boyhood home. His company closed two years later.

The highway signs bearing Harry Darby’s name went up in 1990.

KCQ did run across another way the family’s legacy lives on in the Sunflower State.

Darby and his wife Edith raised four children, all girls. Joan, the second oldest, married a fellow University of Kansas graduate, Roy A. Edwards.

In 1992, KU opened its Edwards Campus in Overland Park-- the name chosen to honor both Roy and Joan Darby Edwards for their years of service and support to the Jayhawk cause.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.