Nelly Gone: KCQ Traces the Kidnapping of Nell Donnelly

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Kate Hill | lhistory@kclibrary.org

For nine days in December 1931, a sensational story gripped the front pages of The Kansas City Star and Times. Wealthy fashion designer and manufacturer Nell Donnelly and her chauffeur had been kidnapped on December 16. Less than two days later, both were released safe, due in part to the efforts of a former mayor and U.S. Senator, as well as an underworld crime boss. The manhunt for the perpetrators would continue into 1932.

But it would take more than 70 years for all the details of the incident to become public.

A reader recently tasked What’s Your KCQ? – a community reference partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Star – with recounting the events of the Nell Donnelly kidnapping. Here’s what we found.

Abduction

Nell Donnelly is perhaps better known by the name of her clothing label, Nelly Don. She founded the business in 1916, based on her idea that women deserved more fashionable clothing to wear around the house. Her designs proved popular, making her a millionaire within a few years. By the end of the 1920s, the Donnelly Garment Company employed more than 1,000 workers, most of them women.

Around 6 p.m. on Wednesday, December 16, 1931, Donnelly arrived home from work, driven by her chauffeur George Blair. As Blair turned into the driveway at 5235 Oak St. (now the site of the National Museum of Toys and Miniatures), he found it blocked by another car and braked quickly to avoid hitting it.

A man stepped in front of the Donnelly car and pointed a gun at Blair. At least two men immediately climbed into her vehicle. One pushed Blair to the floor at gunpoint and blindfolded him.

Another man in the back seat attempted to put a sack over Donnelly’s head. She would later recount how she “got [her] Irish up,” trying to fight off the attacker and screaming as the car was being driven away by the kidnappers.

A short time later, Donnelly and Blair were transferred to another vehicle. After about an hour of driving, they were deposited in a small, “filthy” house in an unknown location and tied up in the same room.

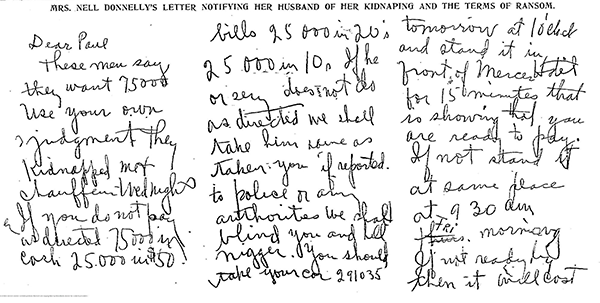

Donnelly was forced to write a ransom note for $75,000 (more than $1.3 million today). The kidnappers threatened if that she did not comply, they would kill Blair and permanently blind her. The note was delivered the next morning to the offices of Donnelly’s lawyers.

Search

Donnelly’s absence had been noted at home. It was routine for her to return in time to feed her newly adopted infant son, David, before he went to sleep. Realizing she was late, her husband Paul assumed she had gone to dinner with friends. He later phoned several people, but no one had heard from her. Paul had been ill for several weeks and finally went to bed, believing Nell would come home.

Lawyer James E. Taylor arrived at his office the next morning and found the ransom note. He left for the Donnelly house and broke the news. Paul agreed to cooperate with the kidnappers: pay the ransom and not alert the police. It was also decided to call James A. Reed.

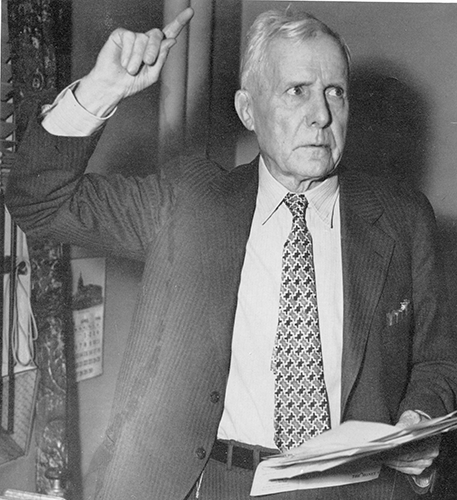

At the time, Reed was preparing for a trial in Jefferson City. The former mayor of Kansas City and three-time U.S. Senator was another of Donnelly’s attorneys, and a close friend and neighbor.

Reed received the news before the court session began. After the judge had taken his seat, he approached the bench and requested a postponement. He explained that Nell Donnelly had been abducted and he was needed in back in Kansas City. The judge agreed, and Reed sped home.

He apparently failed to convey the need for secrecy. Reporters at the courthouse soon learned why the trial had been delayed. When Reed reached Kansas City that afternoon, the press was at the Donnelly home and the police had publicly launched a full-scale investigation.

Clues were scarce. Donnelly’s car had been found behind the Plaza Theater between Alameda (now Nichols) Road and 47th Street. But there was no indication where the kidnappers had taken her or Blair. By the evening of December 17, no new leads had been announced.

Reed issued a statement guaranteeing that the abductors would get their ransom if they released Donnelly, warning: “If a hair of Mrs. Donnelly’s head is harmed, then these men will be brought to justice if it takes the rest of my natural life and all of Mr. Donnelly’s fortune.”

Unknown to the public, someone had placed a call earlier in the day to an individual described in newspapers as “a North Side leader, known to have a wide acquaintance.” The caller demanded that the Kansas City mob find Donnelly. The North Side leader agreed to help and work with the police.

Rescue and Release

The Star later recounted the resulting scene: “More than twenty cars plunged through streets and alleys on the North Side when word went out to free Mrs. Donnelly from the kidnappers. It was like an election day. Those men in the cars were armed.”

Donnelly’s abduction was not sanctioned by Kansas City’s organized crime leaders. Using their extensive network of connections, mob members were able to trace the kidnappers to a small farmhouse between Bonner Springs and Edwardsville, Kansas. Realizing they were up against the full might of the local underworld, the kidnappers surrendered.

In the early morning of December 18, a new person entered the house holding the abducted pair and said, “Mrs. Donnelly, there has been a mistake. These men are from out of town. You have a lot of friends. We have come to rescue you.” Donnelly and Blair were blindfolded again and loaded into a car.

They were released on Kansas Avenue in Armourdale and told to walk along the road until someone came for them. After about 20 minutes, a car pulled up and KCMO Police Chief Lewis Siegfried jumped out. Someone had phoned him with the tip that the two victims could be found near Kansas Avenue and 18th Street.

After a brief stop at police headquarters, Donnelly and Blair were taken home, their 34-hour ordeal over. The ransom was never paid.

Manhunt

Donnelly’s and Blair’s statements to the police, along with information collected by mob contacts, led the police to the farmhouse where they had been held. Within a couple of days, two suspects were in custody and a manhunt was underway for more.

Martin Depew, leader of the operation, was apprehended in South Africa and extradited to the U.S. in the spring of 1932. Depew and one of his associates were tried and given life sentences; another received 35 years.

Strangely, in the aftermath of the event, the police and The Star stressed that this was an “amateur” job pulled by outsiders. Depew’s gang was found to have low-level criminal connections to the area but were not major players. Proper Kansas City mobsters would never kidnap a woman – especially without direction from their bosses.

Garment Company, no date. | Kansas City Public Library

The Blairs

George Blair is mostly an afterthought in The Star’s coverage of the kidnapping. He was obviously not the main target of the attack but an unintended victim. He was also a Black domestic employee of one of the richest white women in the city and mostly invisible to the white press.

After their release, The Star briefly recounted Blair’s version of events. The newspaper noted that his wife Savannah had been interviewed by police while he was missing and that both Blairs were considered upstanding citizens.

The African American-owned Kansas City Call printed a different story. The Blairs were indeed known in their neighborhood as good people, the newspaper said, but that did not stop the police from intimidating and roughing up Savannah Blair.

According to the Call:

Neighbors witnessed white police officers pushing Savannah against a wall in her kitchen. One of them slapped her and demanded information on the kidnapping. They dragged her from the house and threw her against a patrol car. When a neighbor tried to intervene, he was beaten by an officer and arrested. The Call reported that Savannah had been arrested as well, though it did not mention how long she was in police custody.

After the kidnapping, Nell Donnelly promised George Blair that he would have a job with her for as long as he wanted one. He worked for her for the rest of his life.

The Donnellys and Reeds

Over the following decades, it was revealed that James Reed had been the one who bypassed police to make the secret phone call to that North Side leader. The leader was organized crime figure Johnny Lazia, an associate of political boss Tom Pendergast.

Reed had coerced Lazia by threatening to purchase radio time to publicly incriminate and denounce his operation and cripple the mob with legal action. Lazia took him seriously and agreed to locate Nell Donnelly.

In the early 2000s, members of Nell’s family disclosed that she and Reed had begun a romantic relationship at some point before the kidnapping. Son David’s “adoption” was a ruse to cover the fact that she and James Reed were his biological parents and avoid scandal.

In November 1932, Nell and Paul Donnelly divorced. She bought out his share of the Donnelly Garment Company for $1 million. He moved to the East Coast, remarried, lost most of his fortune in bad investments and died in 1934.

On December 13, 1933, the 72-year-old Reed married 44-year-old Nell in a small surprise ceremony in front of their friends. Reed legally adopted David. By all accounts, the marriage was a happy one.

James Reed died of bronchitis in 1944. Nell Donnelly Reed continued to run the Donnelly Garment Company until selling in 1956. The business closed in 1978. She died in 1991 at the age of 102.