50 years ago, Cowtown Ballroom ruled an era in Kansas City. KCQ turns back the clock

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Dan Kelly | dkelly@kcstar.com

When the history of rock ’n’ roll in Kansas City is written — if it’s written — the year that will figure most prominently likely will be 1971.

Fifty years ago, Good Karma Productions, Danny Cox, Brewer & Shipley, “One Toke Over the Line” and the freshly opened Cowtown Ballroom intertwined in a way that defined an era.

“What’s Your KCQ?,” The Star’s ongoing series with the Kansas City Public Library, decided to dig deeper into that chapter of our local music history. KCQ typically answers readers’ queries about our region, but several responses to our earlier KCQ on the Pla-Mor Ballroom and its evolution into the concert hall Freedom Palace inspired this story.

The story also is timely. Cowtown Ballroom opened in midtown July 16, 1971, and 50th anniversary celebrations are planned over the next several months, including a concert featuring Cox and others July 18 (which happens to be his 78th birthday) at Knuckleheads.

First, back to 1971.

As the American military fought a seemingly never-ending war in Vietnam and opposition roiled at home, rock music became a major factor in the political climate (check out the new documentary on Apple TV+, 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything).

Kansas City joined that rock music revolution.

Still, the city was more of a jazz and blues mecca than a rock haven. The fact that Brewer & Shipley’s “One Toke Over the Line,” essentially a joke song celebrating marijuana, is arguably the biggest rock-era hit by a Kansas City act gives you an idea about that era’s relative stature.

Suffice it to say, we didn’t produce rock stars comparable to Kansas City jazz legends Count Basie, Charlie Parker and Bennie Moten. But thanks especially to Brewer & Shipley and the Cowtown Ballroom, Kansas City did briefly make a splash on the national music scene.

The most enduring component of Kansas City’s 1971 music scene, however, has been Cox.

Danny Cox talks and sings about the summer of love

Danny Cox: ‘That’s life’

If things had gone differently, Cox might have become the lead singer for Steely Dan. Or he (not Frank Sinatra) might have ridden a recording of “That’s Life” to fame and fortune in 1966.

Instead, he left California and landed in Kansas City, where his career as a rare Black folk musician blossomed. Cox recorded multiple albums and became a Kansas City institution on the music scene and, more recently, in the theater world. But he never had a big single or a huge national profile.

And Cox is fine with all of it.

“There’s a line from a song I wrote, it just says, ‘No matter where you started from, the roads you took along the way, all roads brought us here together today,’” he said. “If I had done anything differently in my life, I would not have my beautiful 10 children, my lovely wife and our 18 grandchildren.”

Cox was there for the creation of Good Karma and the opening of Cowtown, where he played his jazz-and-blues-infused folk music on the same lineups with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, the Ozark Mountain Daredevils, Poco and even the Kansas City Philharmonic (now the Kansas City Symphony).

“There were so many wonderful acts that came through there,” he said. “Steely Dan came through there.

“I was going to be the lead singer for Steely Dan. We had the same record company, and they didn’t like the way their voices sounded. And I thought, to this day, how can they not be Steely Dan without the voices they have? They’re so unique. I said, ‘Nah, these guys got their own thing.’ And I’m glad that I said no. They went on to become one of the greatest acts in show biz.”

His “That’s Life” moment had arrived when he lived and recorded in Los Angeles. A record company imported Ed Kleban, later to become the Tony Award-winning lyricist of “A Chorus Line,” to produce an album with Cox.

“He really knew how to make Broadway productions,” Cox said. “They brought him to Los Angeles to see if he could make pop hits.”

Kleban’s collaboration with Cox produced music that was “Broadway hot but not pop hot,” and Kleban and the record company decided not to release the album.

“Two weeks later, I’m driving down Sunset Boulevard,” Cox said. “All of a sudden, I hear coming on the radio the song that I had recorded but not being sung by me. Frank Sinatra singing ‘That’s life, that’s what people say.’ I’m going, ‘Boy, is he right.’ You can only laugh.”

Cox laughed as he said it.

A Kansas City, Kansas, resident for more than 30 years, Cox has been omnipresent on the local entertainment scene. His first acting gig was as the voice of the plant in “Little Shop of Horrors,” and he played the Ghost of Christmas Present, on stilts, for six years in the Kansas City Repertory Theatre’s annual production of “A Christmas Carol.” In addition, he has made a tidy living doing voiceovers for commercials.

Cox also has written several musicals, including one about the Kansas City Monarchs baseball team called “Fair Ball: Negro Leagues in America.” He will perform it in a Theatre for Young America production in the fall.

Through it all, he has been an important voice for social justice in Kansas City.

“I went to jail in the eighth grade during the civil rights movement; that’s how early I started that,” he said. “So I’ve been doing it ever since, man.”

And despite saying he’s “supposed to be retired,” he remains active musically.

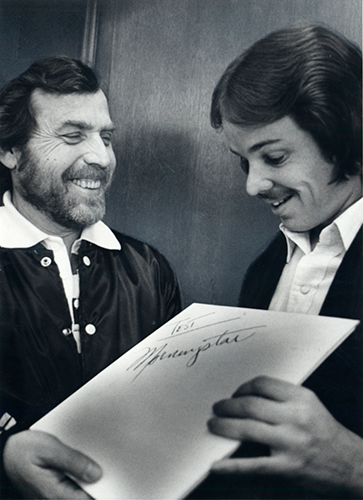

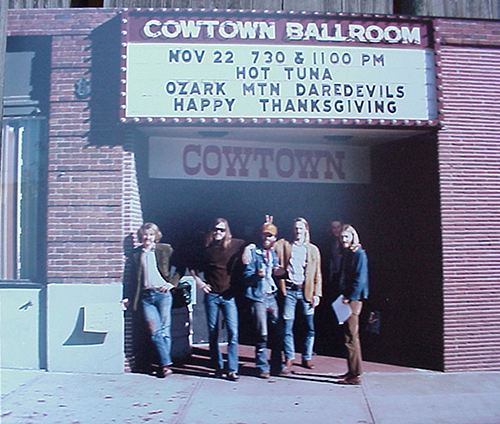

will be on the cover of Cox’s new CD, “Young and Hot — Live at Cowtown Ballroom.”

In fact, he will release a new CD in conjunction with his July 18 birthday show at Knuckleheads called “Young and Hot — Live at Cowtown Ballroom.”

He and Paul Peterson, his longtime friend from the Good Karma Productions days, assembled the CD from 1973 concerts that were recorded for a syndicated radio show. Peterson said he recently found old tapes stashed in a closet and was wowed by several of Cox’s songs.

So was Cox.

“It was magical,” he said. “We were having so much fun. And you can feel it. You can feel the fun of our innocence, joy and all that.”

Peterson had played a role in Cox’s early success, too, as the Good Karma point man arranging college concerts throughout the Midwest featuring Cox and the duo of Michael Brewer and Tom Shipley.

“Danny and Mike and Tom were big hits whenever I booked them, especially Danny,” Peterson said. “Half the audience would get up and follow him off the stage into his dressing room. It was like, ‘Whoever this guy is, we want to know him.’ He’s a very magnetic guy.”

And the Cincinnati native now is very much a Kansas City guy.

In case there is any doubt about his local allegiance, in 2011 Cox recorded an album at Pilgrim Chapel he called “Kansas City — Where I Belong.”

The Good Karma groove

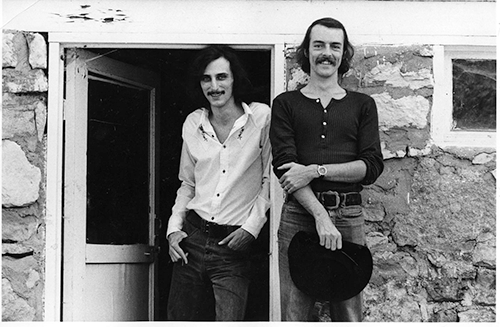

While Cox and Brewer & Shipley toured Midwest colleges, they also lived together in what they call the Good Karma house. They had met playing at the Vanguard Coffee House, which music impresario Stan Plesser had opened in 1963 and where the likes of Glenn Frey (later of the Eagles), John Denver and Steve Martin also appeared.

“I remember we played the Vanguard two weeks over Christmastime once with Steve Martin, who was still working as a banjo-magic act at Disneyland,” Shipley said. “That was when he first started doing is arrow-through-the-head routine.”

The Good Karma house, which was kitty-corner from the Vanguard at 43rd and Main, contained the offices of Good Karma Productions.

“That was the offices on the first floor,” Shipley said. “Michael also lived on the first floor. I lived on the second. And Danny lived on the third. There was music going on there all the time. It was Michael and I and Danny all living together. And it was cool.”

The housemates were the founding acts of Good Karma Productions, which was formed by Plesser with Peterson, Dan Moriarty and Gary Peterson, Paul’s brother. Paul Peterson was a senior at the University of Missouri at the time.

Other musicians Good Karma signed included Ted Anderson, Chet Nichols and, most notably, the Ozark Mountain Daredevils.

“That was back in the hippy dippy days, and we were all friends,” Shipley said. “And the people around us … we figured they were all like Michael and I. A handshake, and you were as good as your word. That was the love and peace thing we had going. But Stan was a business guy.”

“Our wives and girlfriends worked in the basement making posters and flyers. It was a real team effort,” Brewer said. “It was kind of pie in the sky, but it was 1968. What can I tell you?”

As far as Shipley and Brewer are concerned, Good Karma became bad news. They wound up at odds with Plesser, who died in 2011, and left the company in the mid-1970s.

By that time, Cowtown had closed and Good Karma had begun booking large-scale concerts, including the first concerts at Arrowhead Stadium with Paul McCartney and Elton John. The production company lasted until the mid-1980s.

“I stayed to the bitter end,” Paul Peterson said. “At that point, the acts had all been dropped by their labels. There was just nothing happening.”

Brewer & Shipley and ‘One Toke’

The story Shipley tells about “One Toke Over the Line” is that the folk duo had written it “as a joke to make our friends laugh.” But when he and Brewer opened for Melanie at New York’s Carnegie Hall in 1970, they ran out of songs to play as encores, so they broke out “One toke over the line, sweet Jesus …”

“The audience went crazy,” Shipley said. “And the record company president was there. And he said, ‘That’s a single.’ We go, ‘What? Are you crazy?’ But we recorded it, and, of course, it was a hit.”

“One Toke” played constantly on the radio and reached No. 10 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in April 1971. Brewer & Shipley suddenly were big time.

“It was a catalyst for sure,” Brewer said. “Everything changed.”

They played bigger venues, sold more records, gained more fans and attracted way more attention — much of it because of the song’s subject matter.

Some stations refused to play “One Toke.” Politicians lambasted Brewer & Shipley. President Richard Nixon supposedly included the singers on his infamous enemies list (they were not on the original list of 20 enemies from August 1971 but might have been among dozens of later additions that included Barbra Streisand and Bill Cosby).

The song included a side benefit.

“People, when we were doing concerts, they were always throwing joints up on stage,” Shipley said.

Not everybody was in on the toke joke, however. When “One Toke” was at the height of its popularity, Gail Farrell and Dick Dale performed an ironic rendition on “The Lawrence Welk Show,” a conservative, family TV program that raised elevator music to an art form.

“I guess they assumed it was a gospel song,” Brewer said. “I have no idea. I thought it was hilarious.

“The thing that made it extra bizarre was that was exactly the same time the Nixon administration was coming down on us.”

The 50-year-old ‘Welk’ performance has more than 1.5 million views on YouTube.

“One Toke Over the Line,” which was voted No. 8 among “The 15 Greatest Stoner Songs” ever by Rolling Stone magazine in 2011, still gets radio play on oldies stations. With the expanding legality of marijuana, the message might be more pertinent than ever.

Shipley, who lives on a 15-acre property outside Rolla, Missouri, said he got his medical marijuana card recently.

“I first got high the summer of 1964, with honest to goodness Acapulco Gold,” he said. “Something like 57, 58 years later, I’m finally legal. … I’ve always managed to stay one toke over, although I’m not a major stoner.”

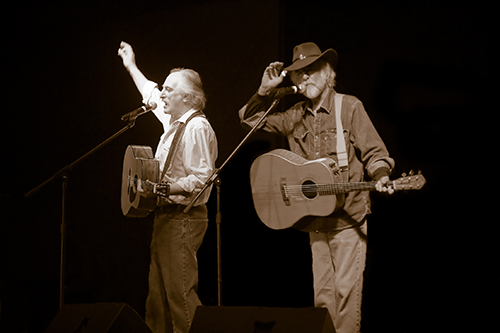

Like Ohio native Shipley, Oklahoma native Brewer enjoys life in rural Missouri these days — in his case, a property near Branson where he has lived more than 30 years. The duo hasn’t performed since the pandemic began, however, and has no plans to do so.

“We’re getting up there in years,” Shipley said, “and I’m not sure how much touring we will ever do again.”

Both singers cherish their time in their adopted hometown.

“I still consider myself a Kansas City guy,” Shipley said. “I still cry when the Chiefs lose.”

“I love Kansas City, always have,” Brewer said. “It’s my favorite city in the whole center of the country.”

A documentary about Brewer & Shipley called “One Toke Over the Line … and Still Smokin’” was released earlier this year and is available on Vimeo.

Cowtown Ballroom

The former Cowtown Ballroom still stands — barely.

The rock concert hall inhabited the second floor of a building at 31st Street and Gillham Road that had housed the El Torreon Ballroom, a jazz club and dance hall before it was converted into a roller rink. Because of a partial roof collapse in 2015, the ballroom area now is unusable.

But it was a sight for smoke-filled eyes when Plesser and the other Good Karma guys saw it in 1971 as they searched for a larger venue for their shows. A real estate friend brought the building to their attention.

“We went over with him to this roller rink that had been closed for years and walked in,” Paul Peterson said. “We just went, ‘Boy, oh boy. This is the place.’”

It had no stage and no seats, just a huge wooden floor with an overlooking balcony. The Good Karma guys installed a stage using old bowling lane boards, and the venue was ready to accommodate about 2,000 standing, sitting, squatting, sweating fans.

“It was meant to sort of seem like a Sunday in the park, only indoors,” Peterson said.

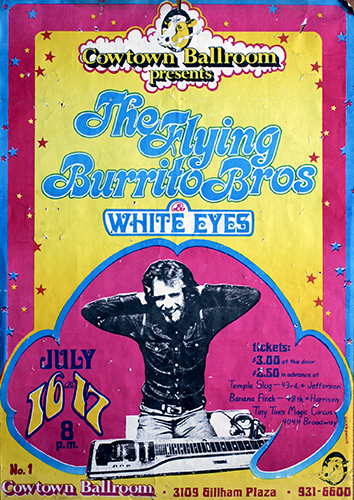

Cowtown Ballroom opened with the Flying Burrito Brothers and local band White Eyes on July 16 and 17, 1971. Peterson said the early concerts were “a little rocky.”

“We really didn’t have sound and lighting very well in hand at that point,” he said. “It was still pretty rough.

“Other early stuff, I’ll be honest, some of that is a little foggy. It was foggy in the room. We were foggy at the time.”

Ah, yes, the fog. That didn’t roll in from the river.

Rumors suggest that toddlers who came with parents (no liquor was sold, so there was no age limit) left the room high on marijuana — as did everybody else.

“Oh, my god yes,” Shipley said. “I remember when the Kansas City Philharmonic played there, there was smoke everywhere. They weren’t used to that, and they weren’t used to people applauding at the end of a violin solo or something like that. That actually blew them away.”

The Philharmonic played at Cowtown several times.

Other regulars included Cox, Brewer & Shipley, Poco, the Ozark Mountain Daredevils and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, who played there six times. Martin opened for the Dirt Band three times.

From classical to folk to blues to rock and beyond, Cowtown covered the full spectrum of music: Steve Miller Band, Frank Zappa, Alice Cooper, Taj Mahal, Foghat, Hot Tuna, Ravi Shankar, The Byrds, B.B. King, Van Morrison, Linda Ronstadt, Paul Butterfield, Leo Kottke and many more. Including Whizzo the Clown.

All for $4 or $5 — or less. The Philharmonic concerts cost $1.

“The crowds were just absolutely incredible,” Cox said. “We were trying to live up to our name of Good Karma, and that’s why the tickets were so cheap. It’s so funny when you look back at some of the ads and see what the prices of the tickets were. You almost have to laugh.”

Joe Heyen spoke with many old Cowtown fans among the 102 interviews he conducted as producer and director of the 2009 documentary “Cowtown Ballroom … Sweet Jesus!’”

“I heard over and over and over again, ‘That was the best time of my life,’” he said. “Boy, we heard that so many times.”

Heyen, who also runs a Cowtown Ballroom Friends Facebook group, will appear at several area showings of his documentary in the coming months, including July 15 and 17 in the El Torreon building.

The El Torreon, the site of church services in recent years, now houses an event space on the first floor. The building’s operators have established a nonprofit in the hopes of restoring the upstairs room to its former glory.

Cowtown Ballroom eventually succumbed to the needs of invading rock bands and the bladders of local music fans — along with the fact that Good Karma never made any money from the place.

“A lot of the new English bands that we were starting to book, their power requirements were getting bigger and bigger, and we could not meet some of that,” Peterson said. “And there were complaints there weren’t enough restrooms.”

The Cowtown’s final show Sept. 16, 1974 featured the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and Brewer & Shipley, ending a righteous reign of 38 months.

“It wasn’t there for very long,” Brewer said, “but while it was in operation, sure was a whole lot of music being played there.”

Cowtown 50th anniversary events

- “Cowtown Ballroom … Sweet Jesus!” screening, 7 p.m. July 15 and 17, El Torreon, 3101 Gillham Plaza; also, open house 2-5 p.m. July 18. Free; donations accepted for restoration of the El Torreon/Cowtown Ballroom. facebook.com.

- Danny Cox birthday celebration, CD release and Cowtown 50th anniversary party, with Larry Knight, Max Groove, Lonnie McFadden, Joe Cartwright and Kent Rausch, 7:30 p.m. July 18, Knuckleheads. $25. knuckleheadskc.com.

- “Cowtown Ballroom … Sweet Jesus!” screening plus live music by Rick Bacus, Janet Jameson and John Anderson, 7:30 p.m. Aug. 4, Lemonade Park. $20-$30. lemonadeparkkc.com.

- “A Cowtown Revival” with Danielle Nicole Band, Danny Cox & Friends, The MGDs and The Clay Kirkland Band, 7 p.m. Sept. 10, Folly. $40-$60. follytheater.org.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.