A Little Devil in America: FYI Book Club Selection Is a Rueful Celebration of Black Artistry

A longer version of this story, written by the Library’s Steve Wieberg, appeared in the April 18, 2021, edition of The Kansas City Star.

It has been a little more than 51 years since gospel singer Merry Clayton made her way, in pajamas and curlers, to a Los Angeles recording studio to belt out some of the most memorable backup vocals in rock music history. The hour was late, around midnight. Clayton, who was pregnant, had been called out of bed. But she practically blew Mick Jagger away on the track for the Rolling Stones hit “Gimme Shelter.”

Raaaape, murderrrr. It’s just a shot away. It’s just a shot away.

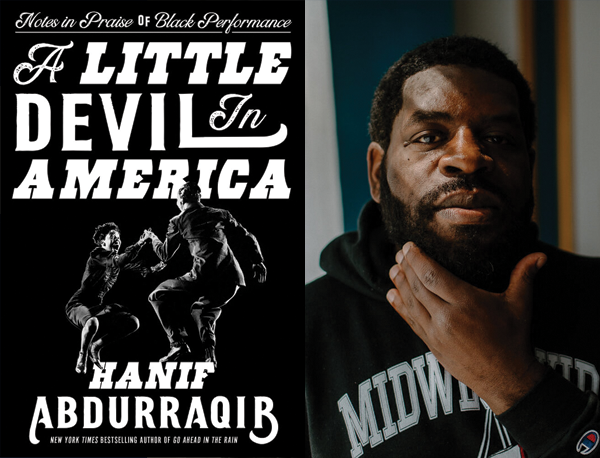

Hanif Abdurraqib joins the legion of admirers in his new book A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance. “It is good,” he writes, “to sing the word ‘murder’ like you fear it, but better to sing the word like you aren’t afraid to commit it.”

By Hanif Abdurraqib

Thursday, May 27, 2021 | 6:30 to 7:30 p.m.

Online book group discussion.

As always with Abdurraqib, there’s more to take from that incendiary 1969 recording session and from Clayton’s long career than that. He tempers his remembrance with lament, first that, tragically, she suffered a miscarriage shortly after returning home. Maybe it had been the strain of the session. There was no way to know.

But it was also the fact – and here is where Abdurraqib adds perspective – that while this powerful Black singer was coveted by the likes of the Stones, Joe Cocker and Carole King for her backing vocals, she never could carve out more than a moderately successful career as a solo artist. Clayton was denied the full measure of fame she helped create for others.

“Even the greatest singer who is relegated to the background has a hard time expanding out of it,” Abdurraqib writes. “To be known in this way is to be barely known at all. To be buried in history, in a grave with no marker for your name.”

That – the invisibility of too many talented African Americans until they can fill some need, serve some purpose beyond the Black universe – is one of the themes that courses through A Little Devil in America. Released March 30, it reaffirms the 37-year-old Abdurraqib as one of our country’s most incisive contemporary writers, be it through prose or poetry. He produces both, the rhythms of one frequently bleeding into the other.

The Kansas City Public Library has made A Little Devil in America its latest “book-of the-moment” FYI Book Group selection.

The title comes from a speech by flamboyant, St. Louis-born entertainer Josephine Baker at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. “I was a devil in other countries, and I was a little devil in America, too,” she said just ahead of Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic “I Have a Dream” address.

Baker is among those featured in the book, a penetrating meditation on Black culture and creativity and its place in broader American culture. Abdurraqib weaves personal stories and reminiscence with sharp analysis in illustrating how Black people have historically lifted and inspired other Black people, in many cases through performance. Always, however, there is the specter of racial divide.

A Little Devil in America by Hanif Abdurraqib

While white Americans may share an appreciation for Black artistry, Abdurraqib observes that it’s too often only as consumers. It’s artistry as a commodity.

Dave Chappelle, whose brilliantly discomforting Chappelle’s Show ran on Comedy Central from 2003 to 2006, “got to be everyone’s Black friend for a while. The one that stays at a comfortable enough distance but still provides a service.

Singer Whitney Houston was packaged as a white-digestible pop princess, to the point of provoking African American backlash. “In order for her to take on the pop world like no Black woman musician of her era ever had before,” Abdurraqib notes, “she had to be written about in a way that placed her above and outside the narratives of other Black musicians.”

Abdurraqib also examines the effortless cool of Soul Train host Don Cornelius, Aretha Franklin’s ability to make songs “close to something holy” and Beyoncé’s stunning homage to the Black Panther Party at halftime of the 2016 Super Bowl in Santa Clara – “a tribute to one of her people’s most revolutionary movements, in the place of that movement’s birth … with a message so loud it didn’t have to be spoken in order to be heard”

Kirkus Reviews calls the 37-year-old Abdurraqib “a writer always worth paying attention to.” His first collection of essays, 2017’s They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, was named a book of the year by Buzzfeed, Esquire, NPR and Oprah magazine, among others. He was longlisted for a 2019 National Book Award for Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to a Tribe Called Quest, a chronicle of the pioneering hip hop-group that became a New York Times bestseller.

He has released two collections of poetry, both to acclaim. A Fortune for Your Disaster won the Academy of American Poets’ Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize last year as the “most outstanding book of poetry published in the United States.”

Abdurraqib, who lives in Columbus, Ohio, recently spoke with The Star about A Little Devil in America, poetry vs. nonfiction, and his perspective on Black excellence and race relations in our nation. Excerpts are edited for length.

INTERVIEW

Q: There’s a lot in A Little Devil in America to take in. What did you want to stick with readers?

A: I hope people take away … a curiosity to explore these histories on their own terms and think a bit more deeply about humanity as it relates to consumption, which I think is challenging for all of us – myself included.

I didn’t come to this book from a position of self-righteousness or that my ideas on this are finished. Of course, like every Black person in America, I think I have a unique perspective on the way humanity is devalued in the name of celebrating things. But I did not want to present myself as an authoritative voice or someone who’s wagging a finger, so to speak. I’m asking people to understand that there’s importance to honoring the full life of someone beyond what they can provide you by way of consumption.

Q: You express an inner anguish about the state of race relations today, at one point writing, “I have yet to be given enough in this country that might silence the ache that arrives when a video of a Black person being murdered begins to make the rounds.” Are we failing in this era of Black Lives Matter to move the needle?

A: It depends on how you define it. I don’t think the needle has moved to my satisfaction. But I’m also aware and hopeful that there are ways it’s moving that I just won’t see, that I won’t be aware of yet … and that 10 years from now, I will look back and say, “OK, I can see how this thing and this thing and this thing led to the world I’m living in now.” It’s just hard to see that in the moment.

Q: You have some interesting reflections on violence … between boxers in the ring, youngsters in schoolyards, even you and your older brother. Are you speaking to its inevitability? Does some degree of violence serve a purpose?

A: I think so. I think rage serves a purpose. I mean, violence is embedded into the very fabric of American history. To me, to reform that – the country as it is – is at some point going to require violence to some degree. I also talk a bit about gangs and how violence is a tool of protection. I don’t want to gloss over that, either.

Now, I am not someone who wishes for interactions to come to violence. But I also understand that violence is a tool in the larger toolbox of revolution, of quote-unquote resistance, of reimagining a better world. Is it a tool I personally reach for first? Absolutely not. But it’s a tool that I think is almost required to understand all that I can be capable of in order to protect the people I’m fighting alongside and fighting for. And to protect the imagination of a future that serves us all.

Q: Your poetry seems to seeps into your narrative, into this book. How did the blending of genres evolve?

A: The biggest thing, and it might be the least exciting answer but it’s true, is that I don’t really think about it. Part of it is because so much of my poetry … shares the function of storytelling. I just think language, beautiful language, is a vehicle for that. It’s like a vehicle … to draw people in or draw people closer to a long, winding story.

For me, it’s not necessarily blending genres. It’s just returning to my toolbox and asking, “Well, what do I have at my disposal that will make people stick around a little longer? What will keep people here?”

Steve Wieberg, a former reporter for USA Today, is a senior writer and editor for the Kansas City Public Library.

ADD TO SHELF