How Dolly Parton came to mean so much to Kansan Sarah Smarsh that she wrote this book

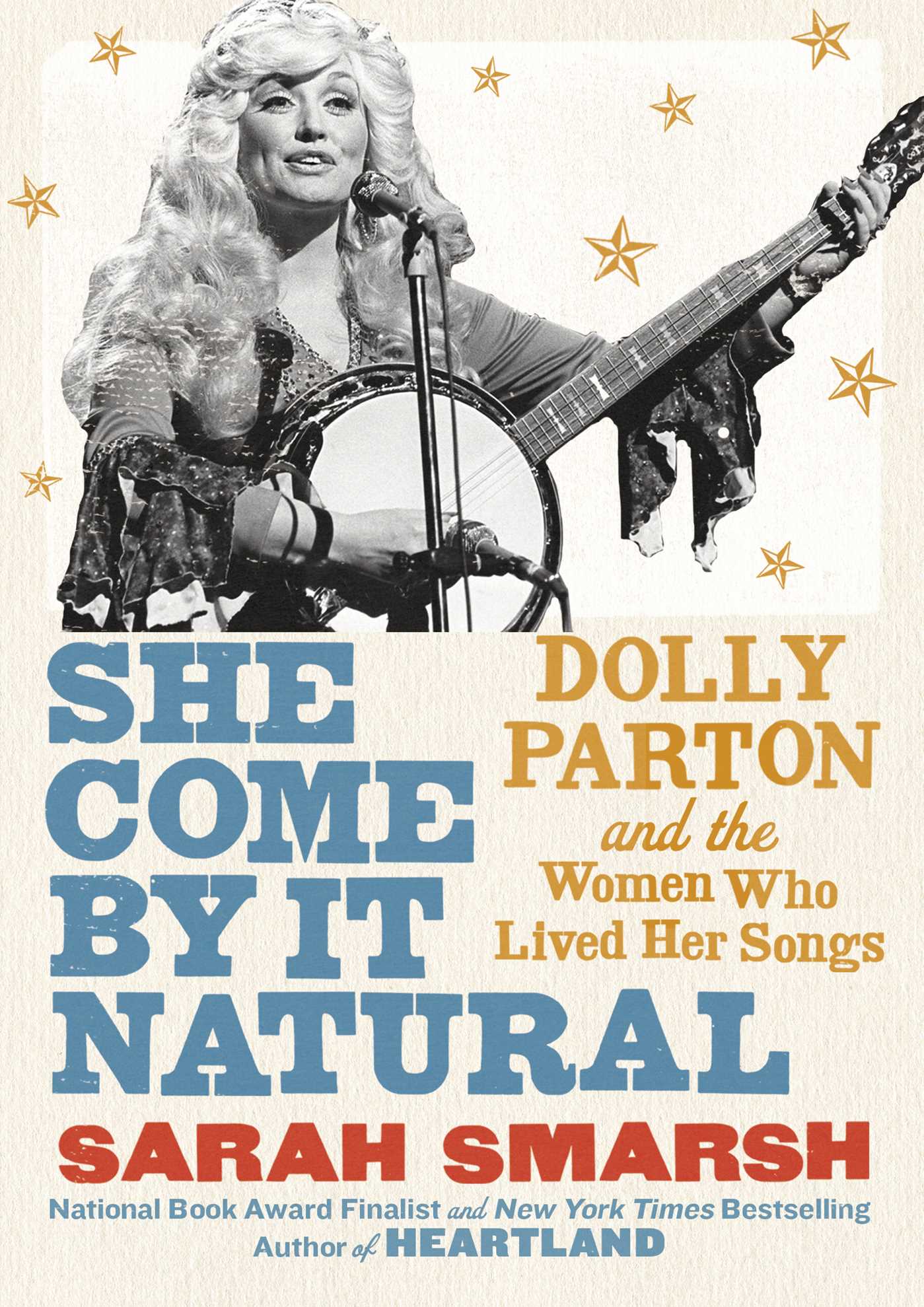

She Come by It Natural: Dolly Parton and the Women Who Lived Her Songs

by Sarah Smarsh

Thursday, March 4, 2021 | 6:30 p.m.

Via Zoom

RSVP or get more details to join the conversation.

DETAILS + RSVP | List of past FYI Book Group selections

The spare, hand-to-mouth world in which Sarah Smarsh grew up in rural Kansas held little room for emotion, or at least emotional display. So, her memory has held tight to the times when she and her Grandma Betty rode down some flat stretch of highway and the older woman would slide a Dolly Parton track into the car’s tape deck. And begin to tear up.

“She’s not a woman I ever saw cry or express any negative feelings or attitudes about her past. For that matter, there wasn’t much discussion of the past at all,” Smarsh says.

“It struck me as quite significant.”

Smarsh was a kid at the time but already forming an understanding of how country music spoke to those in poor rural areas, living one hard day at a time. In the case of Parton, a country icon, that was more than a matter of skillful songwriting and performing. She’d also lived the kind of disadvantaged life she often sings about and that women, in particular, in Smarsh’s family and so many others knew or still know all too well.

Parton exemplified the best in them, their character and strength and resolve — the stuff that gets lost in local yokel stereotypes. She didn’t just survive, ultimately escaping and making good as a singer. She also started her own record label. She co-founded a film production company. She built Dollywood. She amassed an empire worth hundreds of millions of dollars, managing never to lose sight of her roots in the dirt-poor hollers of Tennessee.

That spoke, and continues to speak, to multitudes more.

Smarsh explores her transcendent appeal and cultural impact in “She Come by It Natural: Dolly Parton and the Women Who Lived Her Songs.” Originally published in four parts in 2017 in No Depression, a quarterly, print-only roots music journal, it was released as a book last October with a new foreward by Smarsh and edits for streamlining and cohesion.

The Kansas City Public Library has made the profound study of “a living national treasure who defies easy categories” its latest FYI Book Club selection. Late last month, “She Come by It Natural” was named one of five finalists for a National Book Critics Circle Award in nonfiction.

Smarsh’s affection for Parton is part organic, having been raised to a country soundtrack heavy on the Judds, K.T. Oslin, Janie Fricke and Lorrie Morgan, as well as Parton, Tammy Wynette and other earlier-generation stars. It was her grandmother’s reaction that brought Parton into particular focus, she says.

Decades later, Smarsh was compelled to look deeper. She was finishing her first book, “Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth,” a critically acclaimed best-seller that delved into her family’s generational poverty on a farm west of Wichita and the burdens of social class. The 2016 presidential election was approaching, laying bare the country’s growing polarization.

But there was Parton, riding the waves of a new No. 1 album (“Pure & Simple”) and sellout after sellout on a national concert tour (that included a stop at the then-Sprint Center in Kansas City). Gray hair in her crowds mixed with tattoos and piercings, trucker’s hats with rainbow T-shirts. Social media gave the same universal love, and how often did that happen? Parton belied the fraught tenor of the time.

“Maybe it’s no coincidence,” Smarsh writes, “that Parton’s popularity seemed to surge the same year America seemed to falter. A fractured thing craves wholeness, and that’s what Dolly Parton offers.”

No small part of that is a generosity of spirit illustrated by Parton’s monthly $1,000 checks to families affected by the Great Smokey Mountain wildfires of 2016 and, just in the past year, a million-dollar donation to the Vanderbilt University Medical Center toward development of the Moderna coronavirus vaccine.

Something else impressed Smarsh. Insistent as Parton had been in taking and maintaining charge of her own career, beginning with a break at age 28 from her musical partnership with Porter Wagoner, she has sidestepped any and all attempts to stamp her as a feminist. But make no mistake, Smarsh says. She has walked the walk. That includes owning, as Smarsh puts it, her “hyper-sexualized physical presentation.”

Parton, who just turned 75, is getting the full celebrity-worship treatment in an all-Dolly special edition of People magazine. Smarsh’s book won’t be confused with that. She recently spoke with The Star about “She Come by It Natural,” the personal resonance of the singer’s life and career and how Parton fits into wider discussions of gender and class.

Excerpts are edited for length.

Q: Is it trite to call country music the soundtrack to your life?

A: It was, as a form of entertainment. But it carried much deeper significance than that.

Being from a somewhat marginalized community in (the sense of) both economic poverty and rural isolation, there were very few places in culture where I saw what felt like my home or my people reflected back to me, particularly with any accuracy or dignity. Country music was one. That’s not to say the genre isn’t sometimes problematic and rife with posturing and stereotypes. But it was a place, particularly in music written and sung by women, that was reliably validating for me and the females around me in ways that just weren’t true in television and broader popular culture.

Q: What was your introduction to Dolly Parton?

A: For someone who ended up writing a book that’s very much about her, I didn’t grow up as some sort of Dolly superfan. And nobody in my family was. She was just sort of part of the cultural fabric of the moment. When I was a kid in the 1980s, she was on magazine covers and on every talk show — Donahue, Oprah. She was on Carson at night.

When she sort of embedded herself in my psyche, and when I developed maybe a closer connection with her voice and persona than I had with other country artists, was the moment I describe in the book. When my grandmother was driving down the highway and I was in the passenger seat, as I often was.

Q: It was your publisher, Scribner, that first proposed turning your 2017 magazine series into a book. Why?

A: That’s an interesting question, and I don’t honestly know the answer. I can speculate. They were my publisher for “Heartland.” And while I was working on some other long-term projects, I think my editor wanted to make sure my voice remained a presence in the realm of books and in those sorts of discussions (of class and gender). I also had this body of work lying there that was book-length and written concurrently with “Heartland.”

No Depression was a print-only exercise, which is quite rare nowadays. It has been around since the ’90s and has this very niche audience and readership — it’s for hard-core fans of Americana music — and the vast majority of people never would have heard about (my work on Parton) otherwise.

Q: Three years had passed, closer to four. Did you weigh a major update?

A: The possibility of updating or revising with a heavier hand was certainly there, (but) I ultimately decided it would be kind of a fool’s errand. The way I work as a writer is so in response to the moment, and … 2016 was historic in the annals of progress for women. There was a female presidential candidate. There was a debate about misogyny and sexism in culture and the media. That election year is what gave rise to the Women’s March (the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration in January 2017) and a kind of renewed gusto in the women’s movement. Allowing the book to be a document of its time ultimately was of best service to the reader.

Q: You call Parton “perhaps the most powerful, least political feminist in the world.” Would she be more powerful if she were more political?

A: I think not. She has a unique power in the way she unifies groups that are seemingly in opposition to one another but can readily agree they share a love for Dolly Parton. The reason she can pull that off is she stays off labels. She stays away from explicit political statements.

Her approach is sort of perfect for the moment. We right now have a very tribalistic political climate in which people are wearing their own political labels as identities. Being on one side of that divide and hearing from someone who wears a seemingly opposing label will immediately shut down conversation and any opportunity for persuasion or transcendence of the social ills that plague us.

I think it’s something that’s authentic to her, and also very effective in both creative and business terms, that she meets people where they are. You don’t get a sense of judgment about anyone. People feel safe in her aura, really, and that allows her to make statements and convey ideas where a political polemic or Instagram political statement would garner a backlash.

Q: You were unable to interview Dolly for the magazine series. Did you try again for the book?

A: In 2016, I reached out to her management. She was on tour at the time, and I didn’t end up getting an interview. I think that was probably for the better. It behooves the project that I didn’t talk one-on-one with the subject, the reason being that she’s quite masterful in interviews as a very bright person who has been the subject of media attention for decades. I might have left that interview somehow feeling beholden to her or reluctant to criticize aspects of her business enterprise, as I do in the book. I am unabashedly a fan of hers, but I also maintain some level of autonomy in writing without an interview.

As for following up for this book, we discussed whether that might be a good idea. Ultimately, thinking that it ended up being a blessing that no interview was involved (in 2016), I did not reach out.

Q: Any reaction from Parton, directly or indirectly, about the earlier articles or the book now?

A: I didn’t hear anything after the No Depression series. There are a lot of esteemed members of the country music genre who read that magazine, so it might have made its way to her. I don’t know.

As for the book, my publisher received an email from a woman who was helping in the writing and creation of Parton’s own recent book (“Dolly Parton, Songteller: My Life in Lyrics,” released in November). It was following a review in The New Yorker about my book. She said, “We loved reading that and would love to have a few copies. Would you mind sending them to her management?”

It wasn’t necessarily on behalf of Dolly, but this was someone working very closely with her at the time and I speculated, hopefully, that maybe Dolly herself was aware of it and intended to read one of the copies I sent. I included a note to her in case it ended up in her hands.

Q: If you did interview her, what would you ask? Is there anything about her life or career that needs fleshing out?

A: As I write in the acknowledgments and to some extent the book itself, someone at her level of legend is ultimately a mirror in which so many of us see some reflection of ourselves and perhaps even project things onto her that may or may not be there. I’d love to talk to her about that sort of thing. But ultimately, I’m not a celebrity biographer. That’s really not my bag.

More than asking her questions, I’d love to just talk to her, maybe tell her some stories about my Grandma Betty. She’s almost her exact contemporary — born a few months apart, lived a lot of the stories that Dolly Parton wrote about in songs, and managed to escape herself. I hope the opportunity arises. It’s fun to dream about that conversation.

Steve Wieberg, a former reporter for USA Today, is a senior writer and editor for the Kansas City Public Library.

The Kansas City Star partners with the Kansas City Public Library to present a book-of-the-moment selection every six to eight weeks. We invite the community to read along. Kaite Mediatore Stover, the library’s director of readers’ services, will lead an online discussion of Sarah Smarsh’s “She Come by It Natural: Dolly Parton and the Women Who Lived Her Songs” at 6:30 p.m. Thursday, March 4, 2021, via Zoom. RSVP or get more details on joining in.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

Read along with the Kansas City community and the FYI Book Club with this catalog list of past FYI selections.

EXPLORE THE LIST

9to5: The Story of a Movement is available to stream on PBS for free until March 3rd, 2021.

WATCH NOW