KC Q - Sunflower Ammo

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Dan Kelly

Back in 1942, the federal government uprooted 150 farms in northwest Johnson County as well as the entire town of Prairie Center so it could build an ammunition plant.

That’s the kind of sacrifice folks endured for the good of the country during World War II.

The Elmer Jewett family was one of the lucky ones, however, because the Jewett farm stood just outside the boundaries of the plant, built near the Kansas River just south of De Soto. Still, as the Eudora Weekly News reported on May 14, 1942, the Jewetts didn’t escape the impact of the construction.

A bulldozer knocked down part of the Jewetts’ fence, and cattle escaped from their pasture.

“Mrs. Jewett and her son tried to recapture the cows, but to no avail,” the article said. “She then asked the operator of the errant bulldozer for help. He replied that he was sorry but, ‘This is war,’ and kept on working. Mrs. Jewett agreed that yes, this was war and stood directly in front of the bulldozer until the driver helped recapture the cattle.”

The tale of the iron-willed Mrs. Jewett was one of many uncovered during research into reader Michael Rieke’s submission to “What’s your KCQ?”

Rieke, who grew up in Shawnee and attended the University of Kansas but now lives in Houston, asked, “What’s the story of the WW2 Sunflower ammunition plant outside of De Soto, what company built it, what kind of ammunition it made, etc.?”

“What’s Your KCQ?” is an ongoing series in which The Star and the Kansas City Public Library partner to answer readers’ queries about our region. We find most of our background in The Star’s archives, and the library provides information and photos from its files.

The plant went on to churn out ammo for three wars, leaving a toxic wasteland in its wake. Over the years developers promised to clean it up for all sorts of endeavors: a bioscience lab, shops and homes, and even a “Wizard of Oz” theme park.

But first things first: The original name was Sunflower Ordnance Works, but it was changed to the Sunflower Ammunition Plant in 1963. Owned by the federal government and operated by Hercules Powder Co., a subsidiary of Du Pont, it began producing propellants for small arms, cannons and rockets on March 23, 1943, less than a year after construction began.

These details (and others to come) were taken from a 1984 federal Historic Properties Report. Numbers vary from story to story in The Star’s coverage of Sunflower, so the federal report has been our final arbiter.

How Sunflower began

Other facts gleaned from the Historic Properties Report:

- The actual Sunflower campus covered 9,063 acres.

- The plant originally was intended to produce smokeless powder and TNT, but the Ordnance Department revised the plans to provide facilities for smokeless powder and nitroglycerin.

- The propellant was called “smokeless powder,” but that was, according to the report, a “double misnomer. The material is actually a granulated substance and is considered smokeless chiefly in comparison to black powder, which it replaced as the standard military propellant during the late nineteenth-century.”

- After World War II, the plant produced ammonium nitrate liquor for two years before entering standby status. It was reactivated in 1951 for the Korean War, remaining in production until 1960, then again in 1965 through 1971 for the Vietnam War.

- It became the nation’s first nitroguanidine-manufacturing plant in 1983.

The federal report also provided a description of the impact Sunflower’s construction had on De Soto. Town historian Dot Ashlock-Longstreth wrote:

“At one time there were eight restaurants, some operating 24 hours per day (including their juke boxes with ‘Pistol Packin’ Mama’). Homes had to be opened to roomers; garages, chicken houses, outbuildings converted into living quarters; large buildings converted into bunk bed housings; trailers, unlimited tents, ‘anything with four walls and a roof, became rentable property,’ and dozens slept out in the open yards, if weather permitted, or in cars.”

Another significant source for this KCQ was a 1989 master’s thesis by Kansas State University student Thomas David Van Sant titled “Price of Victory: the Sunflower Ordnance Works and Desoto and Eudora Kansas.” The story of the Jewetts came from Van Sant’s thesis. He also wrote:

- Peak employment during the plant’s construction was more than 24,000.

- Peak employment during regular operations was 12,067.

- By 1945, women made up more than 60 percent of Sunflower’s payroll, and “sexual harassment was a fact of life at the facility.”

- The plant encompassed 4,500 buildings connected by 175 miles of roads and 70 miles of railroad track.

- Van Sant noted that “if Sunflower’s workers all concentrated on gunpowder for .45-caliber bullets they would produce enough in one day to kill every human being on earth, assuming one bullet for every person.”

After World War II

In the years after World War II, Sunflower’s employment and production dropped drastically, even when the plant was reactivated for Korea and Vietnam. So the operators looked for other ways to make revenue. The Star reported in 1950 that Sunflower was home to 12,000 sheep, 250 horses, 75 Brahman steers and bulls and 600 head of cattle. Farmers also paid to use 130 storage buildings for milo, kaffir and corn.

Given the toxic nature of the materials used at the plant, that probably wasn’t a good idea. In 1968, federal reports indicated that several cows had died from contaminated drinking water.

But fear of toxins evidently didn’t affect the plant’s operators. The following classified ad ran several times during 1986 in The Star:

“GOVERNMENT SURPLUS: The U.S. Army at Sunflower Ammunition plant in Desoto Ks is now generating 20-25 tons per day of Calsium-Carbinate (CaCO3). This product is available free of charge if loaded and hauled by the user.”

Again, probably not a good idea.

All production at Sunflower stopped in 1992. Controlled burns eliminated many unused structures in 1997, and the Army designated the plant as federal surplus property in 1998. The Johnson County Commission promptly approved a conceptual plan to develop a model community on the site.

That was the beginning of the twist-filled second chapter of the Sunflower story.

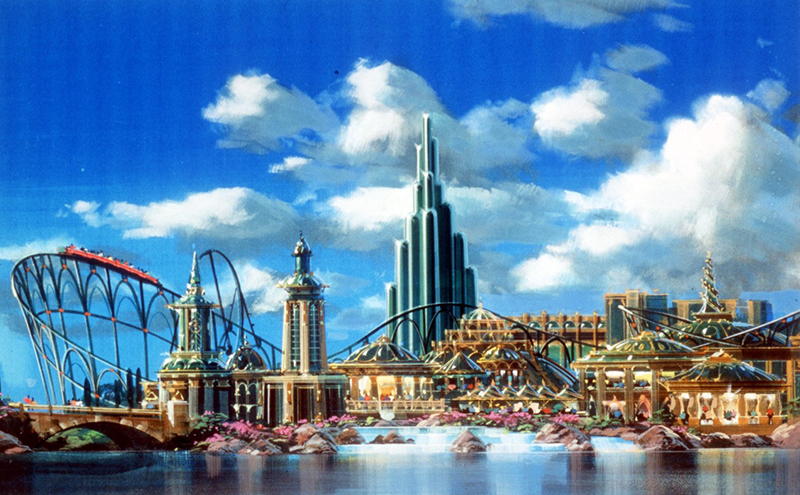

The big headline was when the area nearly became home to the world-famous Wonderful World of Oz theme park and resort. The developers, headed by Los Angeles lawyer Robert Kory, knew that the project would cost hundreds of millions of dollars and that much of that money would go to cleaning up the toxic site. But they were unfazed.

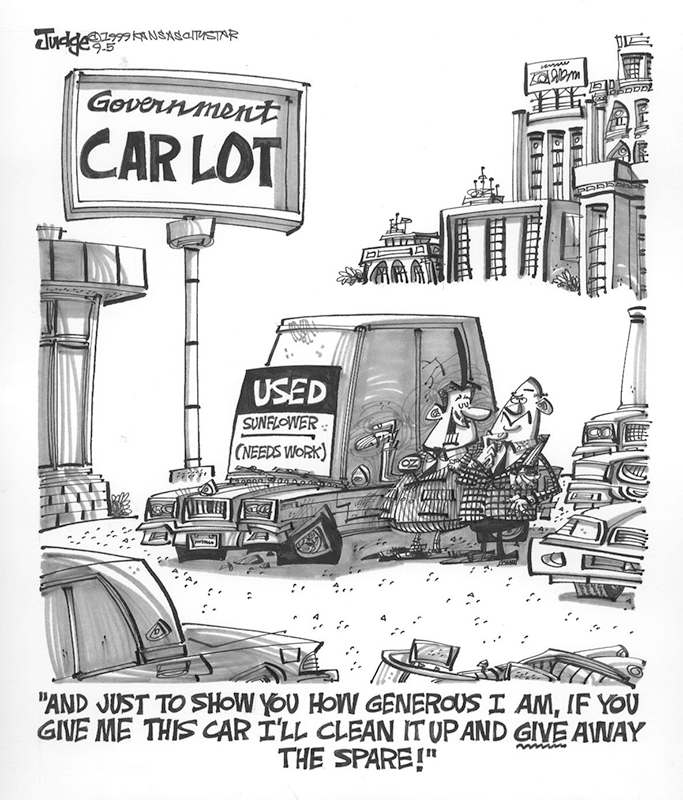

After all, the government would give them the land for free.

Kory told The Star in 2000 that he would be personally liable if something went wrong in the cleanup.

“We’re going to present an absolutely outstanding package, and there are all kinds of reasons why,” he said. “So believe me, it’s going to be really good.”

The Oz idea faced local opposition from Taxpayers Opposed to Oz, or TOTO, and The Wall Street Journal wasn’t much impressed either. It ran a story in May 2001 that carried a De Soto dateline and began: “If a California developer has its way, Dorothy and Toto will once again be off to see the wizard — only this time the yellow brick road will be laid over a toxic-cleanup site that is now so poisonous, cattle aren’t allowed to graze in certain places there.”

As the estimated cost of the project rose to more than $860 million, doubts about Kory’s financing also grew. In late 2001, Johnson County commissioners killed the Oz idea.

About a year later, the Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma sought to reclaim Sunflower, which had been part of its 19th-century reservation lands. Federal judges ultimately rejected that claim, and in 2005 the land was transferred — again free of charge — to Sunflower Redevelopment LLC for private development.

This plan called for shops, residential options and bioscience research initiatives, with 2,000 acres of streamway parks.

“To me this is a dream deal,” said Annabeth Surbaugh, the Johnson County Commission chairwoman then.

Fifteen years later, the dream remains a bit of a fantasy.

Sunflower Redevelopment indicated in 2005 that it expected to complete the cleanup within 10 years, and the Army awarded a $109 million grant for that purpose. Workers found far more contaminants than expected, and the money was gone by 2010 with plenty of work remaining.

After five years of inactivity, the Army agreed to take over the cleanup in 2015, and three years later said some of the land could be ready for development in 2021 or 2022.

But last year, Army officials updated the community on their $200 million efforts: Work was progressing; contractors had dug up sewer lines, removed contaminated foundations and trucked out loads of unsafe soil. The end was in sight — the new target date for completion was 2028.

Don’t hold your breath.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.