When Federal Millions Poured Into Tom’s Town

What’s your KC Q is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Matt Reeves, Missouri Valley Special Collections

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) started as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal to combat the crippling impact of the Great Depression. From 1933 until the start of World War II, New Deal programs doled out federal funds for infrastructure, education, and artistic projects throughout the nation.

Reader Tom Balas knew that WPA workers were busy in Kansas City during that period. He asked KCQ: What building projects did they work on?

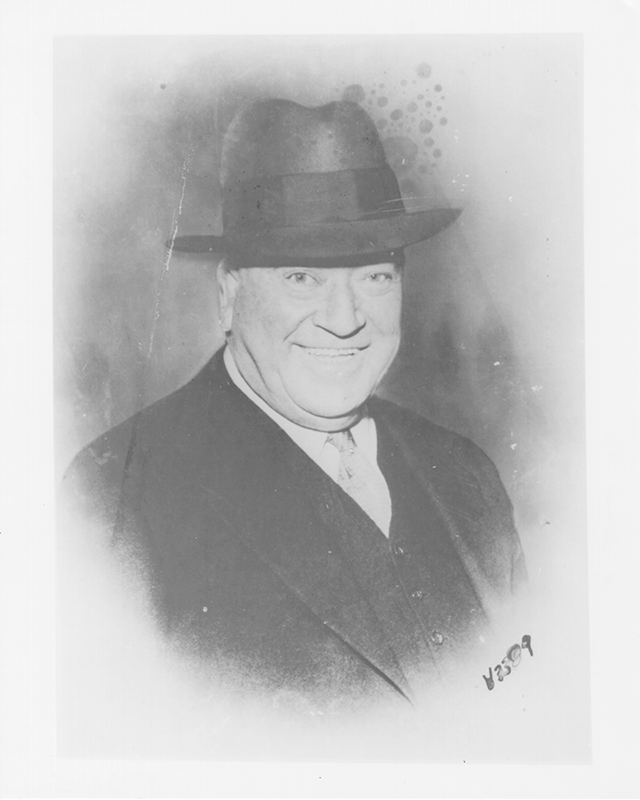

The most visible New Deal buildings continue to define areas of Kansas City’s downtown core. It is difficult, however, to sort out where WPA projects began and those tied to the political machine of “Boss” Tom Pendergast machine ended.

After Roosevelt’s election, it was immediately clear that the New Deal would have a huge impact on the city. “The federal government has opened up its money bags and poured more than a million dollars into Kansas City and Jackson County,” The Kansas City Star proclaimed in 1933. Agencies like the Civilian Construction Corps and the Works Progress Administration invested millions in the city and Jackson County.

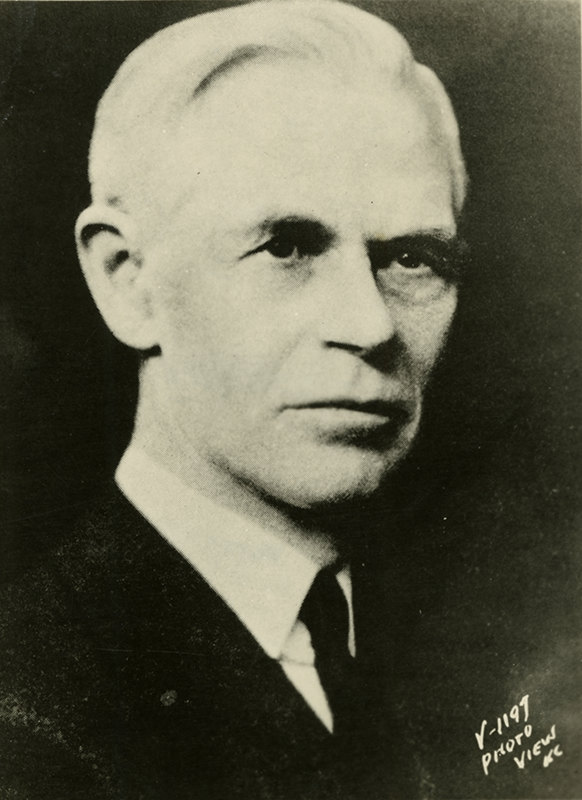

But construction projects were already booming in Kansas City under the direction of City Manager and Pendergast crony Henry McElroy. The city passed a $50 million bond initiative in 1931 to replace aging city buildings with modern structures. Known as the Ten Year Plan, the initiative provided jobs for unemployed laborers during the Great Depression, at a time when Kansas City’s charter forbade direct relief to citizens. But it also was designed to fill the pockets of Boss Tom’s political machine by steering most of the work to Pendergast-owned companies.

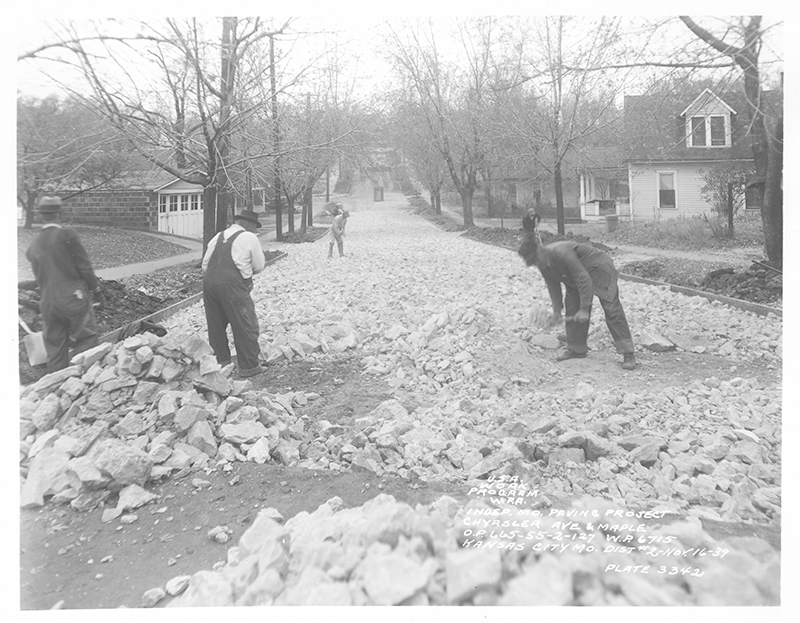

New Deal-era programs did everything from the mundane to the magnificent. Because their purpose was to put Americans back to work, project managers used manual labor even when machines would have been more efficient.

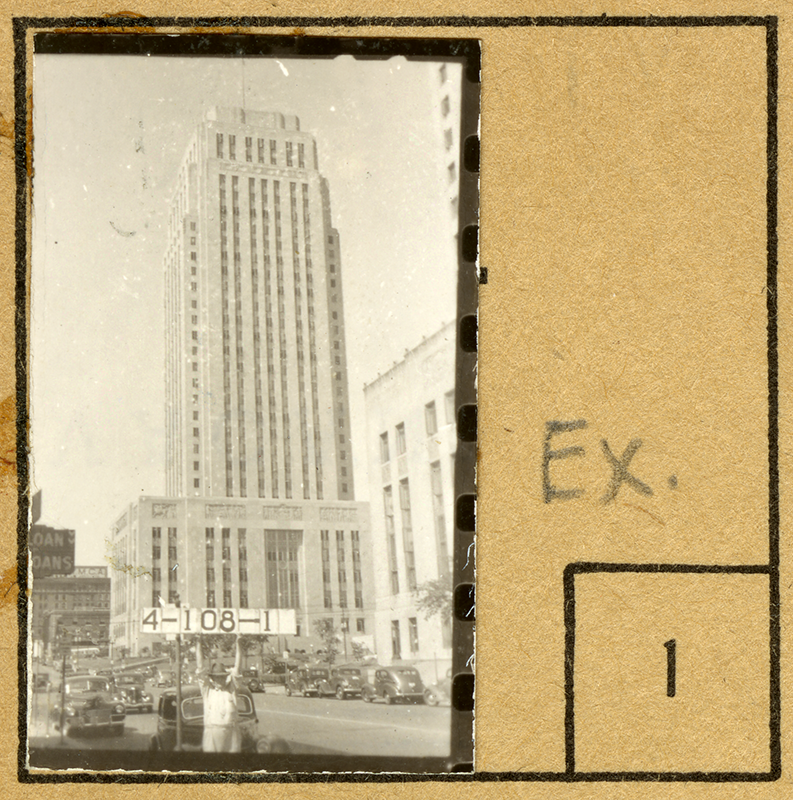

The most memorable New Deal structures towered high above the city’s streets. Tons of concrete, provided by Pendergast’s Ready Mixed Concrete Company, went into buildings like the new City Hall and Jackson County Courthouse.

Both were part of the Ten Year Plan and partially funded by the WPA. The prominent architectural firm Wight and Wight designed City Hall, which opened in 1937. The new county courthouse, just across 12th Street, was completed in 1934. Though not officially named in his honor, the pair were commonly known as “Pendergast’s Pyramids,” a coy acknowledgement of who really ran the show in Kansas City.

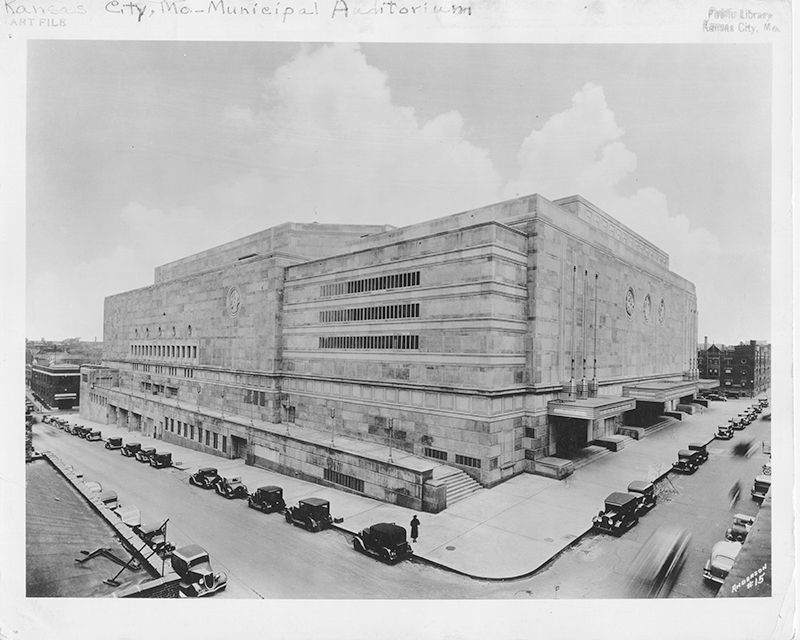

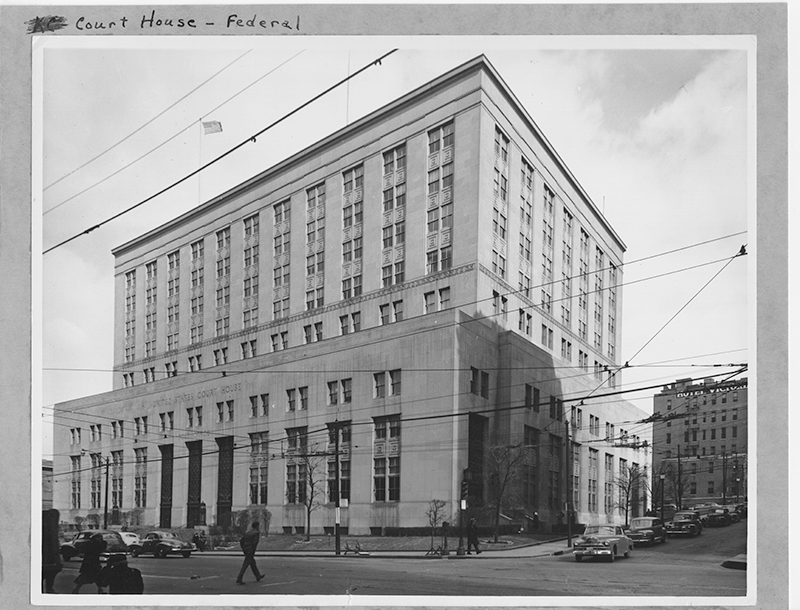

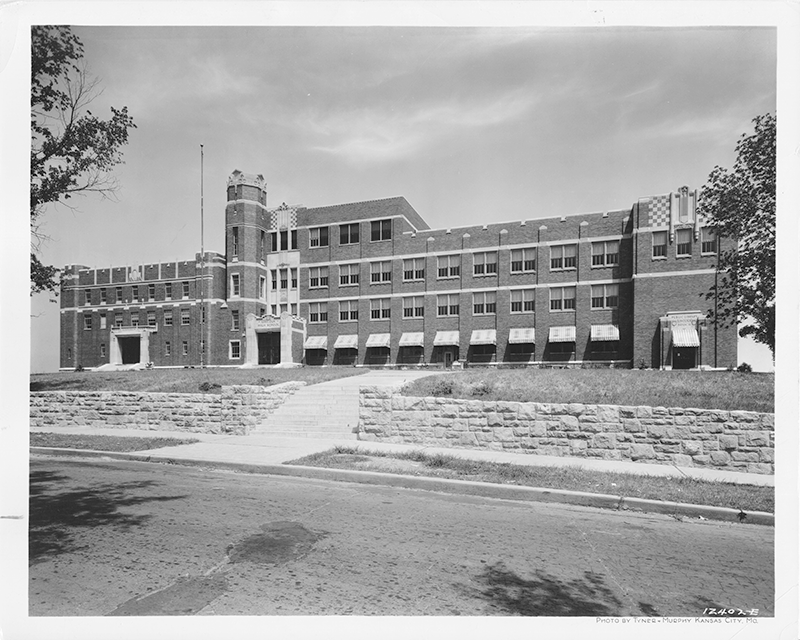

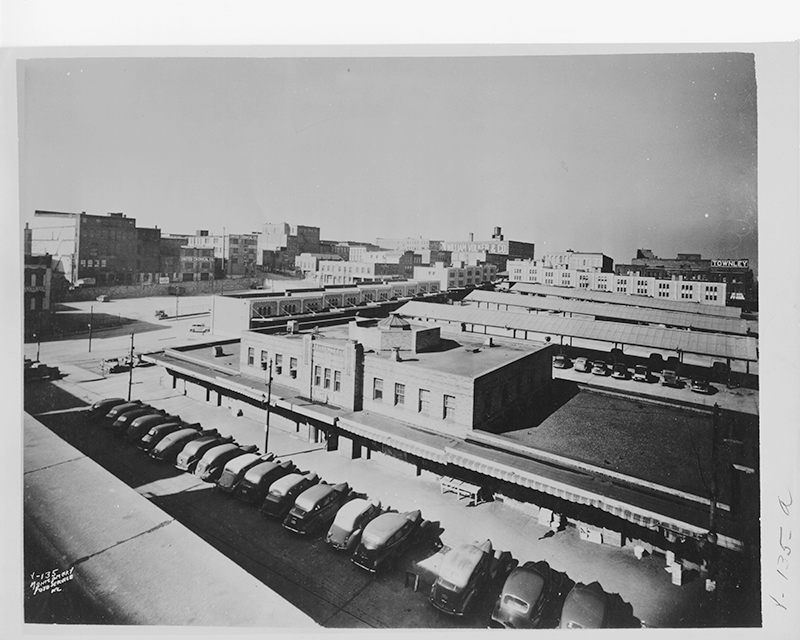

Other notable structures built or partially funded by the WPA included Municipal Auditorium, which opened in 1935, and the federal courthouse and post office at Eighth and Grand. WPA money also went into the paving of Brush Creek; Lincoln High School; and the expanded City Market, which replaced the space where the former city hall stood at Fifth and Main.

Pendergast was indicted for tax evasion in 1939, and federal money for New Deal programs ended with the United States’ entry into World War II a little more than 2½ years later. Pendergast’s hand-picked local WPA project manager, Matthew S. Murray, resigned after his political patron was put in handcuffs, but the New Deal managed to give one final gift to Kansas City.

In 1940, Jackson County officials used federal funds to perform a photographic survey of all structures in the county. These images provided a tool for honest property tax assessment after decades of uncertainty under Pendergast.

After their official use ended at the assessors’ office, the photos found their way to the Landmarks Commission at City Hall. In 2011, the city donated the entire collection to the Kansas City Public Library’s Missouri Valley Special Collections. The thousands of postage-stamp sized pictures provide a window into the past, to a time when federal money flowed, local politicians took their share of the proceeds, and public buildings grew even grander in Kansas City.

How We Found it

Information was gathered from the New Deal vertical file in the Kansas City Public Library’s Missouri Valley Room, Kansas City Star newspaper clippings, the book WPA Buildings: Architecture and Art of the New Deal by Joseph Maresca, and the Library’s 1940 Tax Assessment Photographs Collection. The article also draws on prior research by Kansas City Public Library digital history specialist Jason Roe.

Read More

Read more about this and other KC Q answers with these great books from the Kansas City Public Library's Missouri Valley Special Collections.