All Library locations will be closed Monday, January 19 for Martin Luther King, Jr. Birthday.

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Kate Hill | Kansas City Public Library

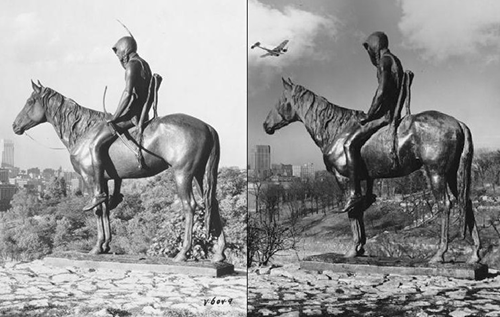

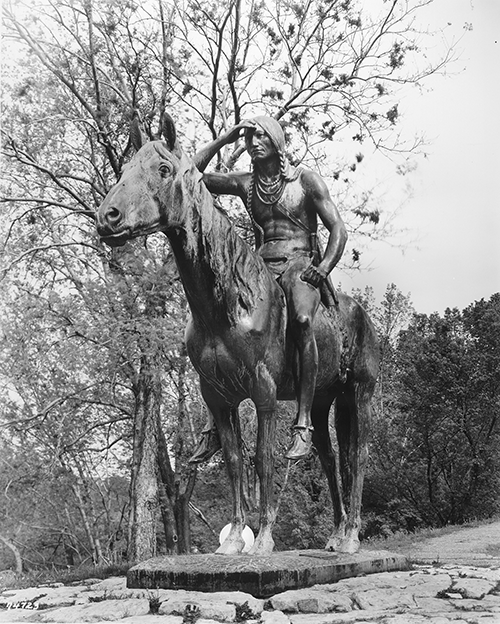

The Scout statue in Penn Valley Park has kept watch over downtown Kansas City for almost a century. Since its dedication in 1922, it has become a favorite subject for generations of photographers.

But look through some of those photos over the years, and you may – or may not – see a few things intermittently missing.

From P1 General Photograph Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections.

Reader Jeffrey Swoyer is a life-long Kansas Citian. He admits that he never paid much attention to The Scout until a visit with an out-of-town friend who had noticed the photographic disparities. Some pictures show the quiver on the rider’s back, some don’t.

Swoyer turned to “What’s Your KCQ,” a partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star that answers questions about the community. He asked, “Is there a story behind the missing quiver?”

The answer is relatively straightforward: vandalism. But the history of vandalism to The Scout: that’s a long story.

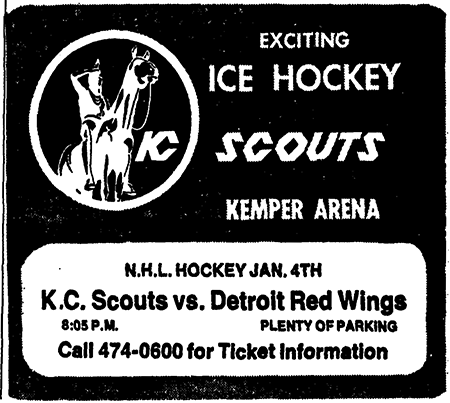

inspiration for their name and logo. Advertisement, The Kansas City Star, January 3, 1975.

From the West to the Midwest

Standing just over 10 feet tall and weighing 1.75 tons, The Scout was originally created for the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, California, by sculptor Cyrus E. Dallin. Dallin was born and raised in the 1860s and 1870s in Utah, and had frequent interactions with Native Americans during his childhood. As his artistic career progressed, he gained national and professional notoriety for his sculptures depicting Native Americans.

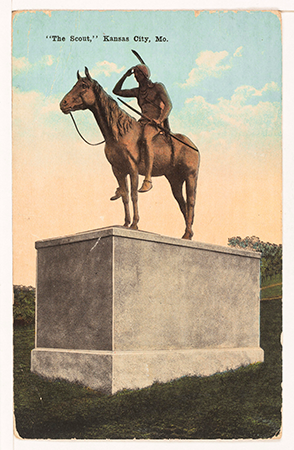

From SC58 Mrs. Sam Ray Postcard Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections.

After the exposition, The Scout was brought to Kansas City and placed on temporary display in Penn Valley Park in July 1916. Who arranged for the statue’s stay is unclear. But news articles of the time indicate it was up for sale, and Kansas Citians had the chance to decide if they wanted to keep it.

Newspapers described a positive public response to the statue. Enthusiastic citizens wrote letters to the editor proclaiming how much they enjoyed The Scout and that Kansas City would be lucky to have such an impressive piece of fine art. A group of Lakota Indians, passing through town that summer with a Wild West show, were reported to be pleased with its authenticity. Plans were soon in the works to raise the requested $15,000 (approximately $352,835 today) for its purchase.

It’s Not Easy Being Bronze

Less than a year after The Scout arrived in Penn Valley Park, The Star reported pieces of it had gone missing. A March 13, 1917, article recounts how a “critic… one night recently decided the arrow which was fitted loosely in the bow held in the Indian’s left hand, ready to be drawn taut, was superfluous. So he climbed up on the pedestal and removed the arrow and the bowstring. Perhaps he thought the Sioux could not completely typify the American Indian until he bore the scars of the white man’s vandalism.”

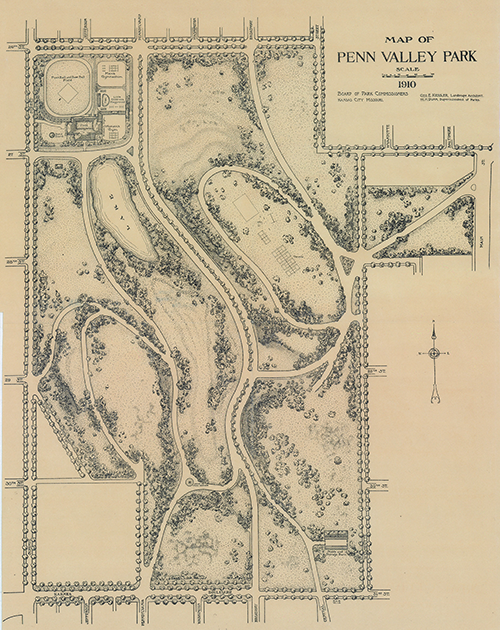

The Scout’s first location was between the park’s lake and Summit Street, just south of where 28th Street used to adjoin the park. On December 30, 1921, the sculpture was moved about 300 feet south and 25 feet higher up the hill to its current home. By then, the arrows in the quiver had been broken and the sides of the statue were scratched up. The Parks Board hoped the more prominent location would deter vandals. It did not.

and a pool is now where Southwest Trafficway and Broadway Boulevard meet I-35.

From SC117 Map Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections.

Newspapers cataloged numerous acts of vandalism of The Scout over the following decades. People carved their initials, names, and addresses into the sides of the horse and rider. In 1925, The Star reported that 21-year old Verna Cowan had been caught scratching her initials into one of the horse’s legs and subsequently fined $25 ($368 today) for defacing public art.

Souvenir hunters removed everything they could, including the bow, quiver, horse’s reins, and feather on the rider’s head. Missing pieces were periodically replaced by the Parks Department, only to disappear again.

From P22 Frank Lauder Autochrome Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections.

Various ideas were proposed to keep vandals away: fencing, landscaping, lighting, guards, and relocation of the statue. The Parks Board spent the better part of 1940 considering moving The Scout to Indian Mound at Gladstone and Belmont boulevards, but it never happened. In 1941, Police Chief Lear B. Reed suggested organizing schoolchildren into “vandalism patrols to guard the art objects of… parks and public vistas.” He thought the measure would deter crime and teach children responsibility and appreciation of civic spaces. The patrols didn’t materialize.

only the heart, but city council members felt it looked too much like a valentine.

From the Vertical File Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections.

One concept the Parks Board kept revisiting was to build a higher pedestal for The Scout, putting it out of reach of damaging public hands. Multiple designs of varying heights and construction materials were submitted over the years, but the project wouldn’t come to fruition until 1960.

From SC35 Robert Askren Photograph Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections.

Repair, Restore, Rededicate

By then, the statue was badly in need of repair. City National Bank & Trust (now UMB) President R. Crosby Kemper Jr. funded its restoration and construction of a new base. The stand was to be more than 8 feet high, made of concrete and natural stone, and slanted outward from the bottom to discourage climbing. After three months in the shop, The Scout was placed on its new pedestal in September 1960.

From P35 Robert Askren Photograph Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections.

The new limestone base likely did deter some vandals from climbing all the way to the top, but it also –inevitably – became a canvas for graffiti artists. And despite its new height, pieces of The Scout still occasionally disappeared and paint was found on it several times. By 2000, it was time for another major restoration. Then-UMB President R. Crosby Kemper III helped finance this round of repairs, completed in 2001.

Advertisement, Kansas City Times, April 29, 1957.

This time, sculptor Jonathan Taggert recreated the missing feather, arrows, bow, and reins, and molds were made of the new pieces, making it easier to replace them when needed. The statue was also cleaned and given fresh wax treatments to protect it from the elements. In August 2002, Mayor Kay Barnes and Parks Board commissioners held a small rededication ceremony.

Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Early in October 2020, visitors to The Scout could find it intact – at least looking from the ground up. Key pieces that had gone missing over the years appeared to be in place. But sadly, and perhaps unsurprisingly, someone had recently applied a can of bright blue spray paint to the limestone base.

Of course, paint can be covered up, cleaned off, or fade over time. It’s nothing The Scout hasn’t weathered before.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.