Saloon Smashing and Sunday Liquor: A Carry Nation KC Q Answered

What’s your KC Q is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Jeremy Drouin, Missouri Valley Special Collections

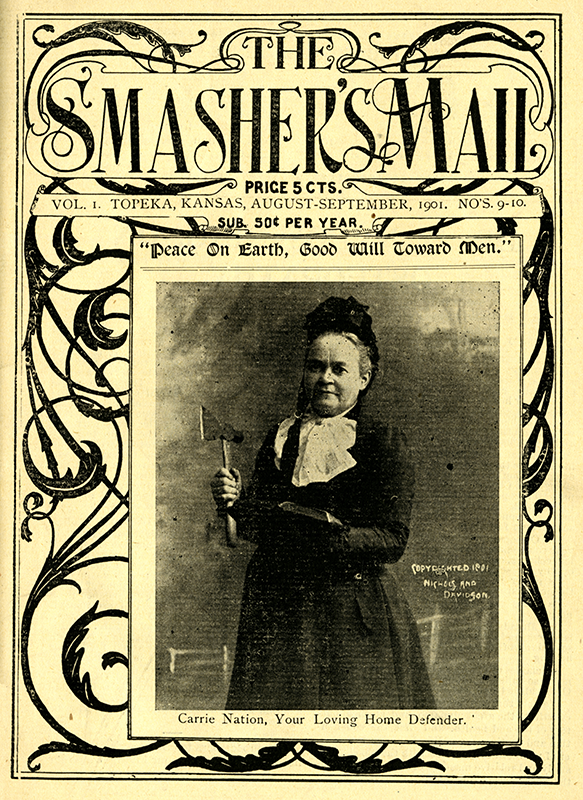

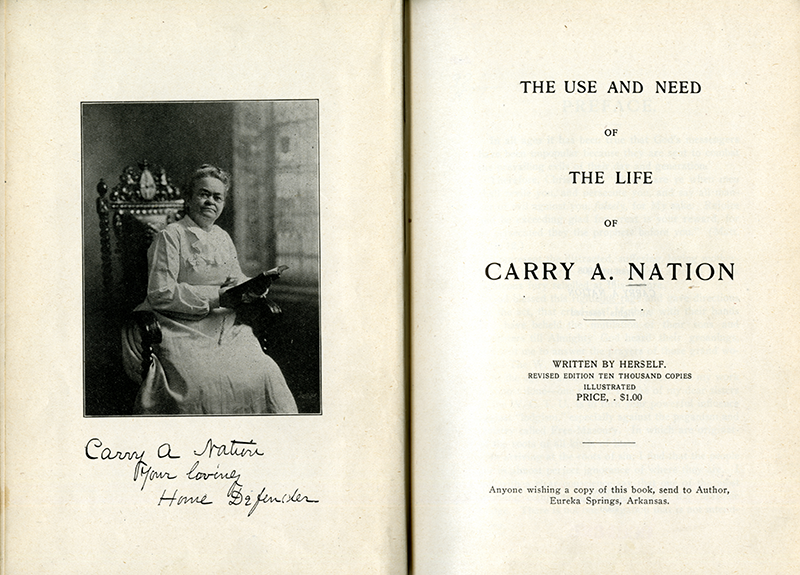

Known for her fiery rhetoric and fierce resolve, prohibitionist Carry Nation earned a national reputation by “smashing” saloons in Kansas and preaching against the evils of alcohol. Her work as a temperance movement leader began in the late 1800s and lasted until her death in 1911.

While most of her barroom damage was done with bricks, stones, and even billiard balls, a hatchet would become the symbolic weapon in Nation’s crusade to rid Kansas and the rest of the country of liquor.

Reader Tom Balas, an admirer of Carry Nation’s conviction and fortitude, had read stories of her taking a hatchet to some of Kansas City’s saloons. He asked KCQ: “Do you know the locations of these bars?”

The historians in the Library’s Missouri Valley Special Collections had to cut through the hearsay and lore surrounding Nation to get to the truth of her saloon busting in Kansas City.

Carry or Carrie?

First, a side note about her name. Born Carrie Amelia Nation in 1846 in Kentucky, she later changed the spelling of her first name to Carry, as she believed her anti-alcohol crusade would “Carry A Nation for Prohibition.”

Carry Crosses the Line – The State Line

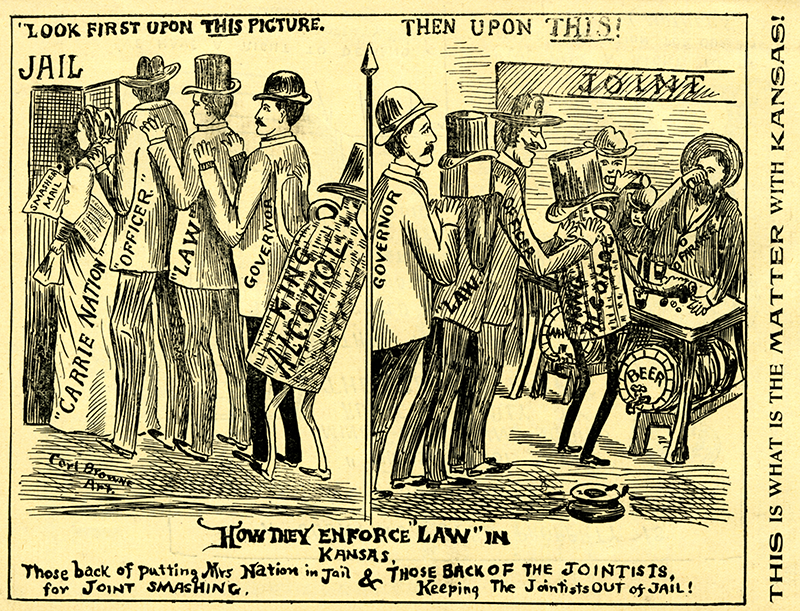

In 1880, the Kansas legislature passed a constitutional amendment prohibiting the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors. However, many bar owners took advantage of legal loopholes and lax enforcement to keep liquor flowing to their thirsty clientele.

Carry Nation and other members of the Kansas chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union resolved to expose and shut down these illegal operations. Not content with prayer-and-hymn protests and other passive approaches, Cyclone Carry, as she was dubbed, took the fight to politicians, law enforcement, saloon owners, and other perceived obstacles to prohibition.

While some temperance proponents accused Nation of crossing the line when it came to demolishing barrooms – her so-called “hatchetations” – there was little doubt that her violent actions brought attention to the cause.

Across the border in Missouri, the decision to allow liquor was left to individual counties and municipalities. The only mandate in some jurisdictions was that no spirits be sold on Sundays. Jackson County was very much wet when Carry Nation came to Kansas City on April 14, 1901 – a Sunday – to participate in a prohibition debate.

Saloon Busting on 12th Street

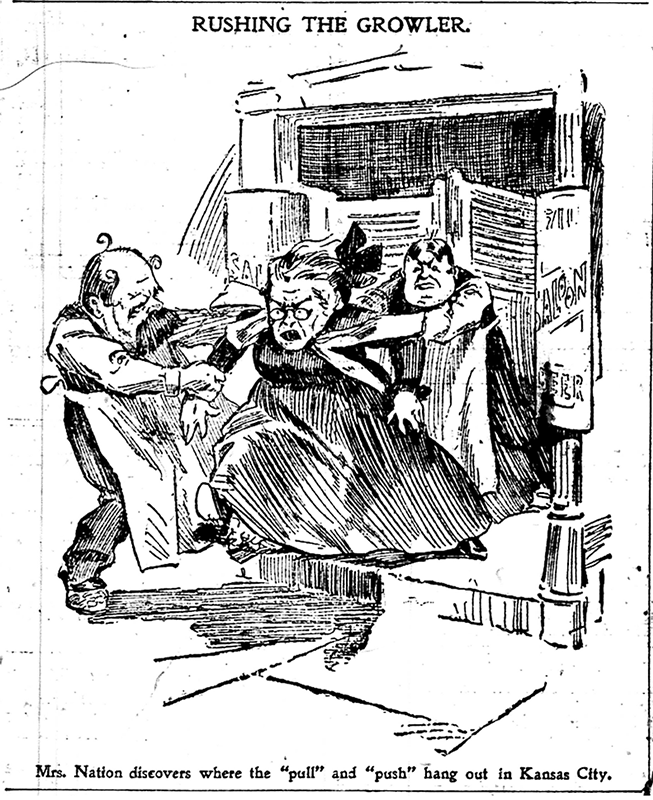

The debate was to take place at Turner Hall at 12th and Oak streets. After learning that the venue was being used for another event, Nation decided to survey nearby saloons to see for herself if the Sunday closing law was being enforced.

She didn’t have to travel far to see that downtown bars, billiard halls, and other liquor joints were open for business. Her first stop was Otto Weber’s saloon, housed in the very building in which the cancelled debate was to have been held.

The Kansas City Star and Kansas City Journal reported that upon entering the establishment, Nation gazed at the patrons and bartender with contempt and proclaimed, “And this is the way the law is enforced in Kansas City.”

She then went table to table, lecturing the “bleary-eyed old men playing cards” that they were on “the high road to hell.”

After the proprietor ordered her to leave, Nation made her way to Quincy’s saloon at the corner of 12th Street and McGee. There, she stood atop a table and preached about the sinfulness of drink.

Content that she had made her point, she continued on to Matthew Flynn’s saloon on 12th Street, between Grand Avenue and Walnut Street.

The bartender at Flynn’s would have none of Nation’s berating. When she complained about a picture of a nude woman hanging behind the bar and called him the “Devil’s own scullion,” he grabbed her by the arm and led her out the door.

A large crowd gathered as Nation continued east on 12th Street to Gus Baughman’s joint. She was met at the entrance by Baughman, who refused to let her inside. Another saloon owner quickly locked his doors as Nation and her growing entourage approached.

Perhaps realizing that other saloonkeepers would follow suit, Nation decided to hold an impromptu temperance rally. A purported crowd of 1,000 to 1,500 blocked traffic between Grand Avenue and McGee Street to hear her speak.

Police arrived within a minutes and promptly arrested Nation for traffic obstruction. She showed the same contempt for the arresting sergeant as she did for saloon operators, saying, “You’re just like the rest of these officers. They are all hell hounds. You haven’t the fear of God nor man. You’re the devil’s own agents and he uses you to carry out his hellish plans.”

Nation spent a short time in a jail cell before a $6 bond was posted by her brother, Judge V. Moore. She returned to his house on Kansas City’s east side, with a police court date scheduled for the following morning.

Carry’s Day in Court

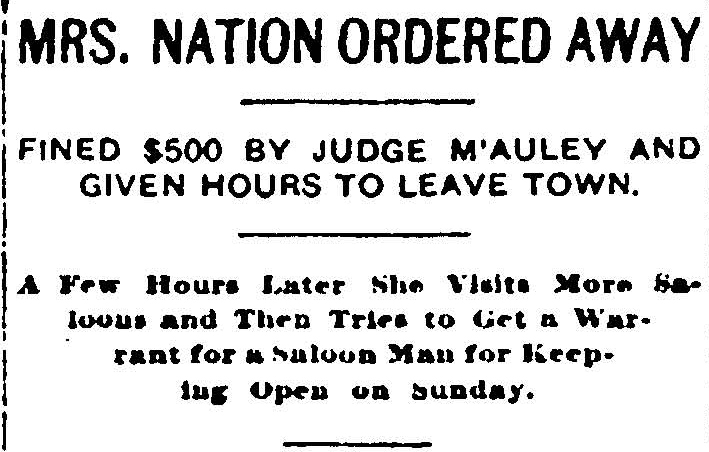

On the morning of April 15, Police Judge T.B. McCauley heard testimony from Nation and the arresting officers. He found her guilty of obstructing traffic, and after the verdict commented: “We are not in sympathy with your methods over here. Missouri is not a good place for short-haired women, long-haired men, and whistling girls…Kansas City is a law-abiding community.”

Onlookers in the crowded courtroom erupted in laughter when Nation responded, “Yes, all of the hell-broth shipped into Kansas comes from Kansas City.”

Unamused, the judge ordered Nation to pay a $500 fine and leave the city by 6 p.m. He threatened to send her to the workhouse for a year if she returned.

As Nation exited police headquarters, where several hundred of her supporters waited outside, she raised a fist in defiance and shouted, “She who fights and runs away will live to fight another day.”

But she didn’t run away.

Nation’s next stop was the West Bottoms, where she was scheduled to give a speech, followed by lunch at a restaurant at Seventh and Walnut streets. Never one to pass up an opportunity to harangue bar owners and patrons, she visited the nearby Morris & Deer saloon to shame its drinkers on their wicked ways.

When one customer questioned what right she had to smash other people’s property, Nation replied, “What right do you have to smash other people’s souls?”

She then led a crowd to Gus Zorn’s establishment at the corner of Eighth and Walnut streets. Nation had protested the establishment previously, demanding that the owner remove a lewd picture on the wall.

Upset to find the picture still hanging, Nation berated the bartender before proceeding across the street to Throck Foreman’s saloon. It escaped her wrath as she proclaimed, “This is a neat, clean place. No bad pictures on the walls.”

The county jail was Nation’s last stop before taking a cable car back to her brother’s house. There, she unsuccessfully lobbied for bar owner Matthew Flynn’s arrest for being open on Sunday.

Later that evening, she left town per Judge McCauley’s court order.

Nation’s Impact

Ironically, the famed “smasher” of saloons did no smashing during her rounds in Kansas City. By the time of Nation’s visit, she had already been arrested several times. Any destruction of personal property likely would have brought longer jail time and the cancellation of paid speaking engagements in the area (needed to offset travel expenses and fines).

While there were no hatchetations in Kansas City, Nation’s harassment of bar owners and law enforcement garnered extensive coverage in local newspapers and impacted city policy.

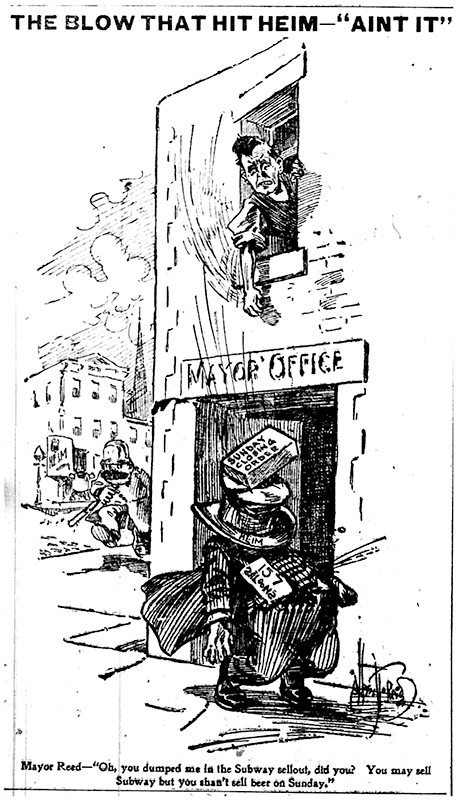

Pressured by the local Law and Order League and fearing that a return visit from Nation would further rally teetotalers, Mayor James A. Reed ordered police officials to enforce the Sunday alcohol ban. Saloon owners were put on notice that, beginning at midnight May 5, Sunday closings would be strictly enforced.

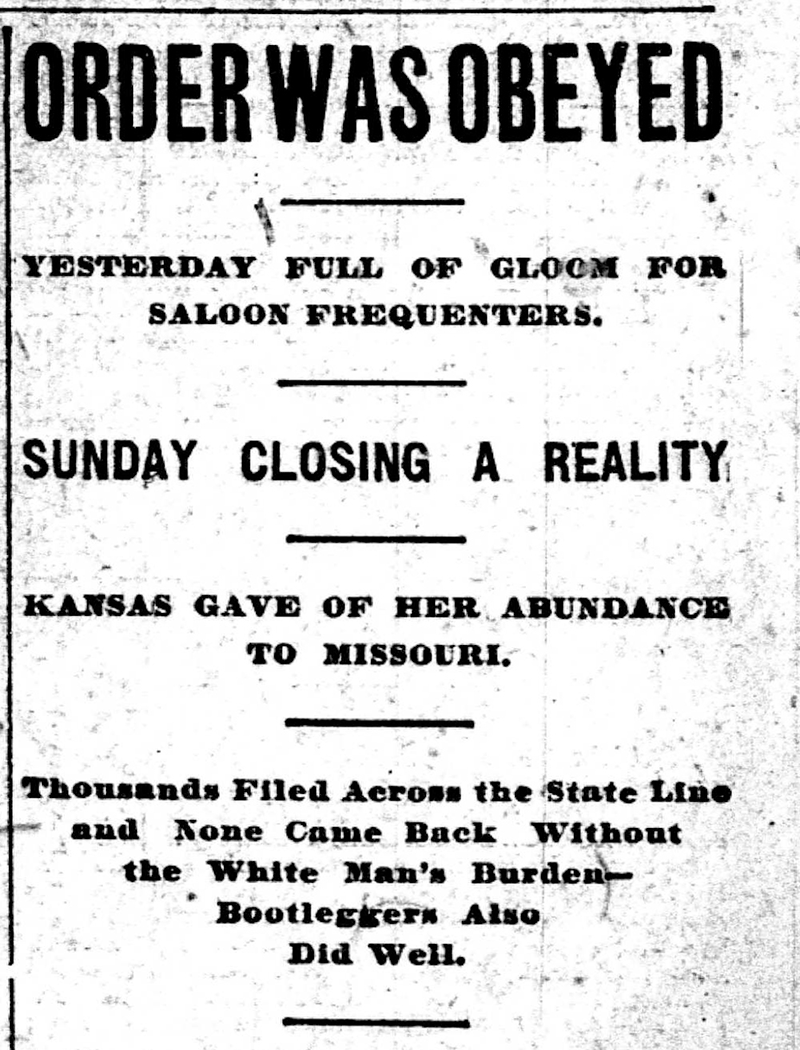

It was reported to be one of the driest days in the city’s history – a victory for Nation and her supporters.

The measure, however, did little to curb alcohol consumption in the city. Newspapers reported that throngs of anxious customers gathered outside their favorite saloons that evening, waiting to be let in at the stroke of midnight.

Bar owners also turned a brisk business selling packaged liquor on Saturdays, helping them make up revenue lost on Sundays. And hundreds of drinkers simply crossed the state line into Kansas City, Kansas, where prohibition was only loosely enforced.

Nation defied her court order and returned to Kansas City a few weeks later to speak at a temperance rally at Union Mission. The event was held without incident.

She would not live to see her dream of national Prohibition, which was enacted nearly a decade after her death in 1911 (and repealed 13 years later).

How We Found It

Detailed accounts of Carry Nation’s exploits in Kansas City were published in the April 14-16, 1901, editions of the Kansas City Star and Kansas City Journal. Quotes were taken from those news reports. Other information was obtained from books and journal articles in the Kansas City Public Library’s holdings.

Many resources pertaining to Nation can be accessed at www.kchistory.org.

Do you have a spooky question?

With Halloween right around the corner, we’re changing things up and asking readers, What’s Your KC Boooooo??? That’s right, we’re asking readers to submit your questions covering notorious hauntings, sinister stories and other eerie happenings in our region. Once we’ve gathered all submissions, we’ll hold a voting round and you’ll have the chance to help decide which spooky question Kansas City Star and Kansas City Public Library staff investigate.