Remembering Alvin Sykes: A ‘Dogged, Deeply Infused Passion’

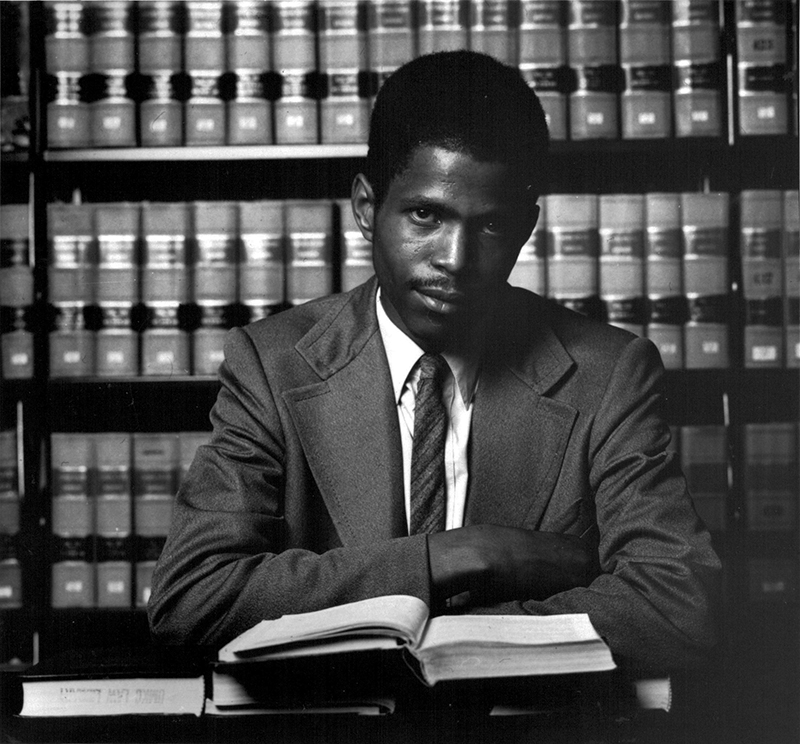

Photo: Kansas City Star

"There was a time," Alvin Sykes once said, "when somebody like me wouldn’t have been allowed inside a library – or as a black man, permitted to read at all."

He devoted a lifetime to righting such wrongs. A school dropout after eighth grade, Sykes became a fixture in local libraries and emerged as a self-taught human rights activist, working though the justice system on behalf of injured parties – particularly minorities and the poor. He wound up writing history, pushing and prodding until Congress enacted the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2008, empowering the federal to investigate long-ago cases of civil rights violations.

In 2013, he was named the Kansas City Public Library’s first Scholar in Residence.

Sykes died Friday, March 19, at age 64. He had been a patient at a rehabilitation facility in Shawnee, Kansas, still recovering from a fall two years earlier at Kansas City’s Union Station. He’d been on his way, he said then, to visit a cousin of Emmett Till.

In an introductory tribute in Pursuit of Truth, a monograph chronicling Sykes' life and work, former Library Director Crosby Kemper III wrote of Sykes' "soft-spoken intensity … combined with a smile and warmth that can disguise his dogged, deeply infused passion."

He "doesn't take 'no' for answer," Kemper wrote. "He takes it as a challenge."

A one-time resident of Boys Town in Omaha, Nebraska, who was raised by a foster mother, Sykes found his calling with the 1980 murder of Kansas City jazz musician Steve Harvey near the Liberty Memorial. As a jazz fan who’d been a friend of Harvey, he was dismayed when an all-white jury found the accused killer not guilty despite incriminating testimony from two accomplices. The defendant could not be tried again for the murder because it would violate the prohibition on double jeopardy.

Sykes devoted months to pursuing a different approach, painstakingly building a case to prove that the killer’s actions constituted a violation of federal laws regarding hate crimes – he had targeted Harvey because he thought he was gay. Sykes convinced the U.S. Justice Department to pursue a conviction, and the perpetrator went to prison.

"So many people have the impression that all my cases are big Steve Harvey cases," Sykes said years later. “They’re not. A lot of them never make the newspaper. A lot of times, people come to me when all else has failed and there are no other options. Often, I look into it and there’s nothing to be done.

"But my brand is that I go for the truth and, if possible, for justice. That formula hasn’t failed me yet. Find the truth. After that, justice may be possible."

The Emmett Till Act, named for the Black teenager murdered in Mississippi in 1955 for allegedly whistling at a white woman, was his signature achievement. Sykes persuaded then-U.S. Sen. Jim Talent to introduce the bill calling for a permanent cold case unit in the Justice Department.

He also pushed an investigation into the 1970 slaying of Kansas City politician and civil rights leader Leon Jordan. Later, among other causes, he worked on legislation to eliminate the statute of limitations on child sexual abuse in Missouri.

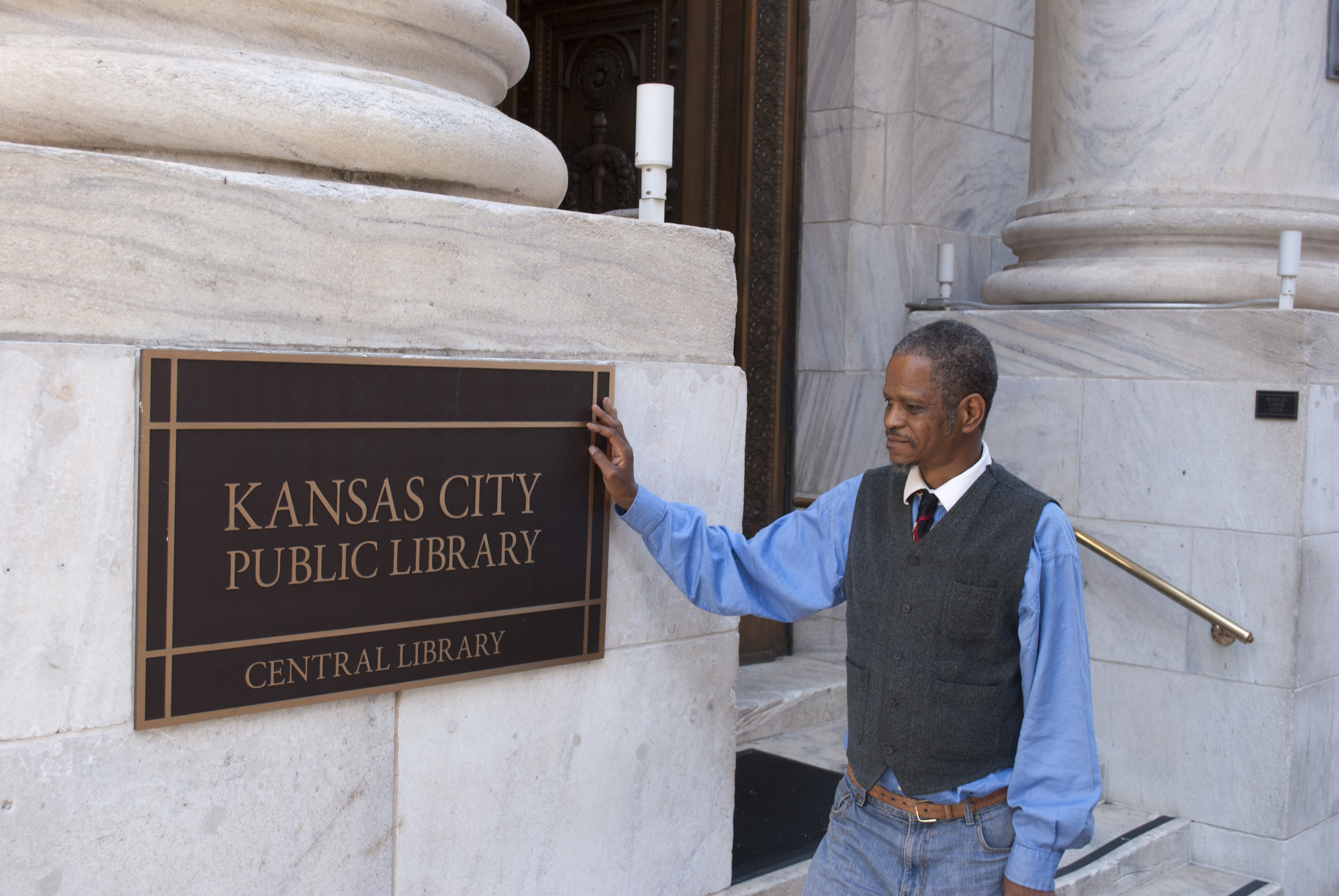

Alvin Sykes outside the Central Library

Sykes called libraries "the great equalizer," looking back on the countless hours he spent reading, researching, and using public computers at KCPL and other public libraries to build his cases. He remained a Library presence, participating in five evening presentations at the downtown Central Library and Plaza Branch.

The last was a November 2016 discussion of Devery Anderson's book Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement. Sykes delivered opening remarks.

Watch or listen to Sykes' past appearances at the Library:

- Alvin Sykes: The Pursuit of Justice for Emmett Till (2009)

- A Conversation with Alvin Sykes (2014)

- Former Sen. Tom Coburn Joins Civil Rights Activist Alvin Sykes for Discussion of Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act (2015)

Additional stories:

- Alvin Sykes, civil rights legend and longtime Kansas City activist, has died (via (Kansas City Star)

- Alvin Sykes, 64, Self-Taught Legal Defender of Civil Rights, Dies (via New York Times)

- Funeral Services Held For Civil Rights Icon Alvin Sykes Who Friends Say 'Bent The Arc Of Moral Justice' (via KCUR)