Of Raiders and Reunions: A KC Q Answered

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

Quantrill.

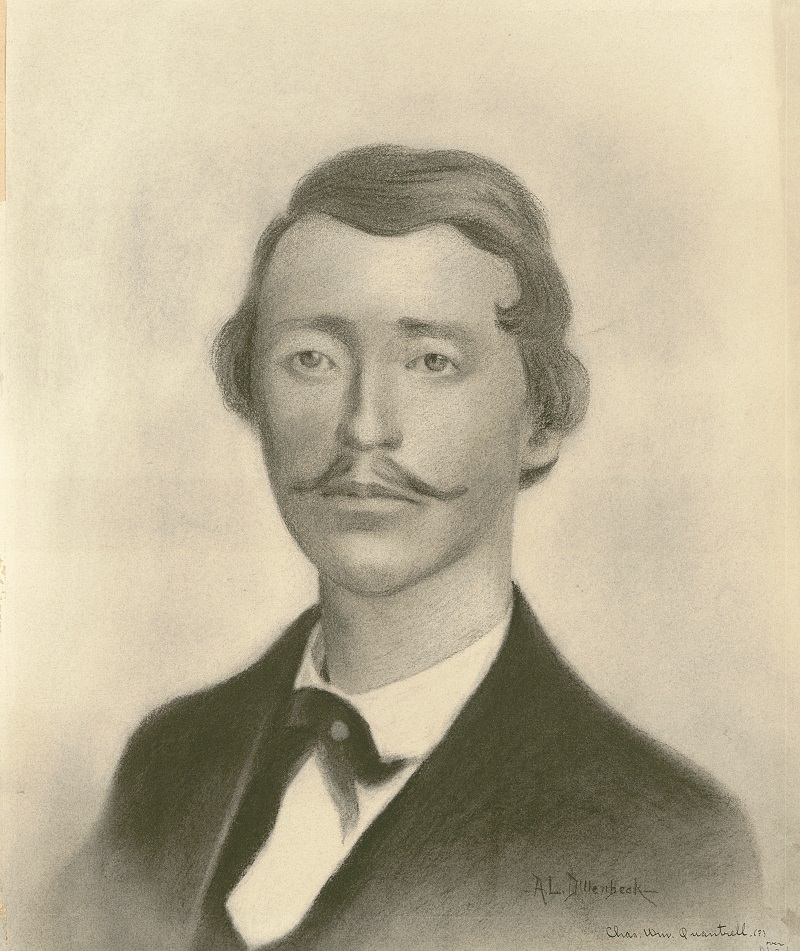

In the Kansas City region, the name is largely associated with William Clarke Quantrill, the infamous Missouri guerrilla who fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War and led a violent raid on the Unionist town of Lawrence, Kansas, on August 21, 1863.

Citizens on the front lines of the bloody Missouri-Kansas border war viewed Quantrill very differently. To southern sympathizers in western Missouri, Quantrill and his band were protectors against raids from Kansas "jayhawkers" and other Union aggressors. On the other side of the state line, his legacy is that of a murderous outlaw on the wrong side of history.

The Quantrill name came up in a recent What’s Your KC Q? submission by Star reader Tony Rome. Rome’s mother attended the old Benjamin Harrison School (now the Kansas City International Academy) near Interstate 435 and East Wilson Road. He recalls her mentioning a “Quantrill Park” just east of the school and asks, “Who was that Quantrill?”

At the risk of reviving old border war animosities, historians in the Library’s Missouri Valley Special Collections searched the department’s newspaper, map, and photograph collections for the answer.

Charcoal drawing of William Clarke Quantrill by A.L. Dillenbeck. Quantrill was fatally wounded in Kentucky on May 10, 1865, during an ambush by Union forces. Kansas City Public Library

While their research uncovered no existence of a city or county park officially bearing the Quantrill name, a large parcel of land at Kansas City’s eastern city limit was found to have ties to the guerrilla chieftain and the cohort of Confederate "bushwhackers" who rode with him.

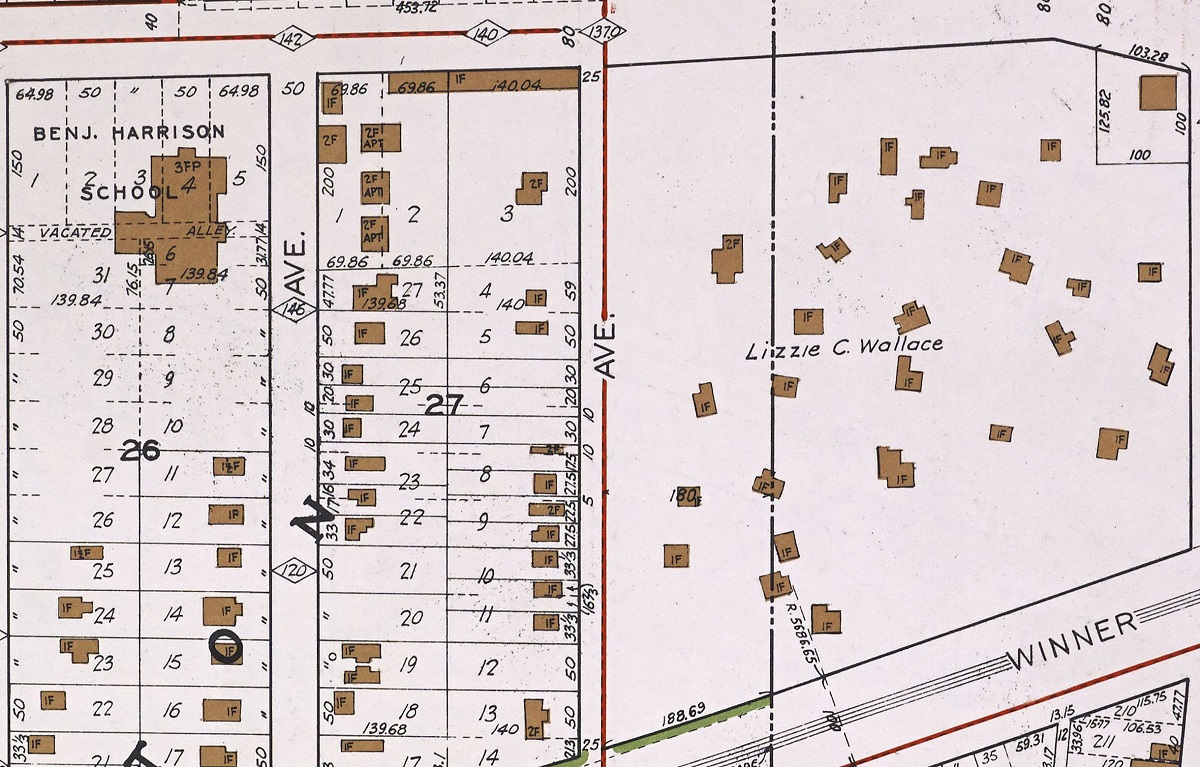

Key to this story is Lizzie C. Wallace. That is the name that appears in a 1925 atlas of Kansas City for a section of land east of Benjamin Harrison School, between Wilson and Winner roads. Shown on the map are numerous small dwellings located on roughly eight acres of property.

Atlas of Kansas City, MO, and Environs, 1925, showing the Lizzie C. Wallace property east of Benjamin Harrison School. The city limit passes through the property. Image: FIMo map database, Kansas City Public Library.

A search of The Kansas City Star and Times archives brings up several articles about Elizabeth (Lizzie) Wallace and the land she inherited from her father, John C. Wallace. The parcel was commonly known as Wallace Grove. Lizzie (known to friends and family as “Aunt E”) lived there with her brother, Jefferson Davis Wallace, and his family, and leased several cottages on the premises.

For nearly two decades, Wallace Grove was the site of annual reunions of the surviving members of William Quantrill’s company and their descendants. The property is likely the “Quantrill Park” referenced in Rome’s question.

Wallace Family-Quantrill Connection

John C. Wallace was a southern sympathizer who built a two-story house on the Wallace Grove property in 1887. The original Wallace farm sat on 2,000 acres that stretched from the Blue River to what is now Mount Washington Cemetery. The heavily wooded grove on the property served as a rendezvous point for Quantrill’s raiders during the war.

The homestead was destroyed by Federal troops sometime after General Order No. 11 was issued August 25, 1863, resulting in the forcible exile of several hundred families in rural portions of northwest Missouri. Issued by Union General Thomas Ewing Jr., Order No. 11 was largely a response to the massacre in Lawrence and a measure to root out bushwhackers and their base of support in Missouri.

The Wallaces fled to safety in Clay County during this period. They returned after hostilities ceased to find their homestead in ruins. Although the family would eventually rebuild, members maintained a steadfast resentment of the North and Union loyalists.

Years earlier, John Wallace was alleged to have been imprisoned by Federals in Independence, Missouri, and sentenced to hang. But he was sprung by Quantrill’s men on the eve of the execution. In gratitude, Lizzie offered to open their family home and grounds for the reunions "as long as a Quantrill man still lived."

The Wallace family home at 8607 Independence Road (now Wilson Road). Kansas City Public Library.

The first official reunion of Quantrill’s raiders took place in 1898 in Blue Springs, Missouri, and was organized by Frank James, older brother of Jesse and member of the notorious James-Younger Gang. Thirty-seven members of Quantrill’s company answered roll call at the inaugural reunion. Subsequent gatherings were held in various locales in eastern Jackson County until 1912, when the Wallace property became the regular site.

Kansas City Star clipping, September 11, 1898.

The two-day reunions at Wallace Grove were lively celebrations with picnicking, music, dancing, and speeches by local politicians. While campaigning as a county judge in 1922, Harry S. Truman gave one of his earliest political speeches on the porch of the Wallace home.

Longtime Independence resident and Kansas City Star contributor Pauline E. Kemp was a young girl living in Wallace Grove in the 1920s. In an August 16, 1968, article, she reminisces about her carefree childhood there, including the festivities surrounding the annual Quantrill reunions:

Politicians made speeches from a platform specially built in the huge Wallace front yard. Civil War veterans, grand in their uniforms, sat on the big front porch recalling their adventures for an eager audience. Night and day the square dancing went on. During this time we children were wild and free. We could eat all we wanted and stay up as late as we liked. Our parents were busy at the reunion.

Another tradition at the reunions was to display a portrait of Quantrill and a company flag. These relics hung above the mantel in the Wallace home the rest of the year.

Attendees of the 1920 reunion at Wallace Grove with a picture of a young Quantrill. A special guest was Jesse James Jr. (front right), son of the famous outlaw. Lizzie “Aunt E” Wallace is back-row center.

Final Muster

Through the 1920s, attendance at the reunions dwindled as the ranks of Quantrill’s band thinned with each passing year. The young guerrilla fighters of the 1860s, some teenagers at the time, were now elderly men in their 70s and 80s. By the end of the decade, only a handful remained.

The 1929 reunion would be the last official gathering of the survivors of Quantrill’s company. The scheduled 1930 reunion was canceled due to a death in the Wallace family and, the following year, the few surviving veterans were too feeble to attend.

1925 Quantrill reunion participants.

Lizzie Wallace remained at Wallace Grove until her death in 1938 at the age of 94. Her brother J.D. Wallace died in 1941. A decade later, his widow donated the Wallaces’ portrait of Quantrill and the Quantrill company flag to the Jackson County Historical Society.

The Wallace Grove property was sold at a public auction in 1967, when the last of the Wallace heirs moved out of the area. Although there was interest in making the home and grounds an historic site, the residence eventually fell into disrepair and was a frequent target of vandals. The home was razed in 1969.

By Jeremy Drouin, Manager of the Library's Missouri Valley Special Collections

For more information about the border warfare that shook the Kansas City region from 1854 to 1865, visit the Library’s award-winning Civil War on the Western Border website.