Central Library has a new parking validation process.

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Dan Kelly | dkelly@kcstar.com

Julia Lee was the queen of Kansas City blues when the city was a center of the jazz and blues universe.

A pianist and singer in the first half of the 20th century, she was a major star — even if her name has since been largely forgotten except among music historians and jazz/blues aficionados.

Reader Amanda Willis remembers Lee, however. She submitted a simple request to KCQ:

I want to know where Julia Lee is buried.

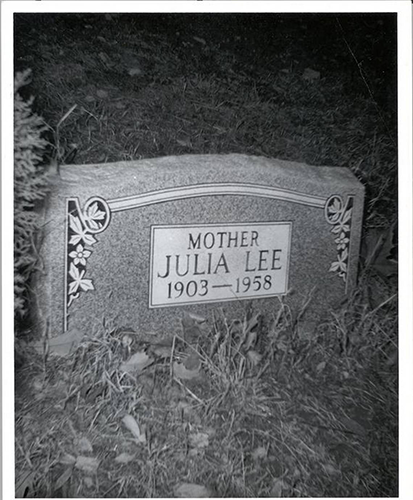

“What’s Your KCQ?” is The Star’s ongoing series with the Kansas City Public Library that answers readers’ queries about our region. In this case, the simple answer is that Lee rests in Highland Cemetery, a historic burial place for local Black people just north of 20th Street and Blue Ridge Boulevard. Jazz great Bennie Moten is buried there too.

But with Julia Lee, the simple answer just won’t do.

as “Snatch and Grab It” and “King Size Papa.”

LABUDDE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UMKC UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

With a bit of prodding, Willis revealed a bit more about her interest in Julia Lee.

“My dad was born in 1930 and worked as a busboy in downtown KC in his teens,” she wrote in an email. “He would sneak into the clubs to listen to jazz and blues. I remember him telling stories about her playing cards and holding her own with the guys in the band.

“… I haven’t been able to find where Julia was buried. She was such a trailblazer, and I wanted to visit her graveside.”

but almost all other sources say it was 1902.

LABUDDE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UMKC UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

Lee was born in Boonville, Missouri, in 1902 or 1903 — the year changes from source to source — and grew up in Kansas City, attending Lincoln High School. She blazed a trail as a Black female musician during an era when segregation was the law of the land and women fought for every scrap of respect they got.

Lee got plenty — from Black and white audiences alike. Jazz was one of the few areas where the races mixed in the first half of the 20th century, at least to some degree. She and Kansas City contemporaries such as Moten and Count Basie played for both white and Black audiences, even if the musicians weren’t allowed to eat at the all-white clubs where they performed.

“Julia Lee was really a big star, not only locally but nationally, because of her recordings,” said Chuck Haddix, co-author of the 2005 book “Kansas City Jazz From Ragtime to Bebop — A History,” which is filled with details about Lee’s career. Haddix also wrote “Bird: The Life and Music of Charlie Parker” and is curator of the Marr Sound Archives at UMKC.

LABUDDE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UMKC UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

Lee could have been even bigger, Haddix said, except she didn’t like to travel.

“And so that limited her touring,” he said. “That really limited her career.”

The racism Black people experienced was one reason Lee disliked touring. Surviving a 1930 car accident that killed a fellow musician also soured her on the road.

So Lee became a fixture at local clubs for more than three decades starting in the 1920s, including at Milton’s Tap Room, which was then at 35111 Troost Ave., for more than 15 years. She ventured outside Kansas City for concerts only occasionally. One exception was when she was a headliner with Count Basie and his orchestra in 1947 at the Million Dollar Theatre in Los Angeles, where Basie introduced her as “the toast of Kansas City.”

Two years later, she traveled to Washington, D.C., for the most memorable gig of her career.

Lee’s popularity had reached its peak, with “Snatch and Grab It” having ranked as the No. 1 R&B song for 12 weeks in 1947 and “King Size Papa” at No. 1 for nine weeks in 1948.

Meanwhile, Harry Truman, another local hero, was on a hot streak of his own, having surprised the experts by winning reelection as president in November 1948. He was a fan of Julia Lee’s, which is how she wound up performing at the 1949 White House Correspondents’ Association dinner, a showcase for comedians in recent years but which then featured a broad array of entertainers.

LABUDDE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UMKC UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

Lee and her drummer, Samuel “Baby” Lovett, were invited to perform along with the likes of Danny Kaye and Arthur Godfrey. Truman was in the audience, which also included Vice President Alben Barkley as well as senators and Supreme Court justices.

“It was really a wonderful surprise for both of us,” Lee told the jazz periodical The Second Line. “When we received the invitation, I sent a telegram to Washington, saying: ‘WHITE HOUSE! WE ACCEPT!’”

The Star’s About Town column by Landon Laird indicated that Lee was a big hit at the event.

“Julia did a couple of encores, and it took some time for Godfrey, the master of ceremonies, to get on with the next act due to the applause and calls for more. Truman seemed to get a big kick out of Julia, despite her rivalry for his Washington popularity.”

And despite her penchant for alcohol-fueled banter and sexually charged lyrics.

The Second Line article, written by Kansas City native Carey Tate two years after Lee’s death, described several conversations Tate had with the singer at performances in the final years of her life.

Among his comments:

“In Kansas City, where she sang blues for more than three decades, she is as famous a name as former president Harry S. Truman, a native of Missouri. Her black lace dresses, glistening bangs and feather plumes in her hair are as familiar to jazz fans as charcoal-broiled steaks from the local stockyards.”

And, “Once, when I was talking to Julia Lee during an intermission, she spoke of a couple of stag bars in the heart of the downtown district which could stimulate even the tiredest of businessmen. ‘The waitresses,’ she said, ‘wore nothin’, if you’d overlook slippers and a cellophane apron.”

The article, like most other pieces about Lee, discussed the popularity of what she called “Songs My Mother Taught Me not to Sing.” Filled with suggestive lyrics and double entendres, they had titles such as “I Didn’t Like It The First Time (The Spinach Song),” “My Man Stands Out,” “In Like a Lion and Out Like a Lamb” and “Don’t Come Too Soon.”

“I like to call my songs ‘risky’ numbers rather than ‘risque’ — that word is too fancy for me,” she told Tate.

Lee’s risky numbers weren’t allowed on the radio, so her popularity relied on record sales, jukebox plays and live shows. The songs still got her into hot water in 1941, as described in Haddix’s “Kansas City Jazz” book:

“Kansas City’s liquor control department banished Julia Lee from returning to Milton’s ‘because of the type of song she sang and the way she sang it.’ … Lee defended herself, simply stating ‘these same songs have been sung in some of the finest homes in Kansas City.’ Influential friends came to Lee’s rescue, and she soon returned to her regular post at Milton’s.”

Samuel “Baby” Lovett holding a snare drum, Vic Dickenson with a trombone,

Benny Carter with a saxophone, Lee (center), Dave Cavanaugh with a saxophone,

Jack Marshall with a guitar and Billy Hadnott with a double bass.

LABUDDE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UMKC UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

Milton Morris, who featured Lee at his clubs for two decades, was one of two Kansas Citians who recognized her talent and furthered her career.

The other was Dave Dexter Jr.

“I first met Julia Lee when I was about a sophomore in Northeast High School,” he told The Star in 1986. “And she’d sit there and play the piano and sing, and she just killed me ’cause she didn’t sound like anybody else.

“And I told her, I said, ‘I’m gonna get you on some records some day.’ And she’d laugh, you know, and take a swig of booze …”

Dexter wasn’t kidding. He went on to become an executive for Capitol Records, where he worked with Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Peggy Lee and, later, an up-and-coming British band called The Beatles.

His heart was in jazz, however, and he kept his word to Julia Lee, signing her in 1944 to a recording contract with Capitol Records.

LABUDDE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UMKC UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

“That was one of the major labels,” Haddix said. “A lot of her contemporaries recorded for smaller labels that did not have national distribution. All the elements for her national success were there, but lack of traveling held her back unfortunately.”

Her greatest commercial successes came with the Capitol recordings “Snatch and Grab It” (which sold more than 500,000 copies) and “King Size Papa,” as well as a slew of other hits, usually of the ribald variety performed under the name Julia Lee and Her Boy Friends.

Dexter, who produced nearly 60 recording sessions with Lee, said her talents went far beyond the risqué songs that accounted for most of her national popularity.

“Boy, Julia could take an old ballad, and she could make you cry. … They’re beautiful,” he said.

Haddix said Lee became “typecast musically” because of the success of her sexually oriented songs.

“She was an accomplished musician,” he said. “She was an outstanding pianist, but that was never showcased. It was eclipsed by her risqué material.”

Haddix described Lee as a musical pioneer, having begun her career in the early 1920s as pianist for her brother’s band, the George E. Lee Novelty Singing Orchestra.

“It was uncommon for women to be in bands as instrumentalists,” he said. “Mostly they were vocalists.”

Lee’s early days also were marked by her marriage to Frank Duncan Jr., a star catcher for the Kansas City Monarchs who later managed the powerhouse Negro Leagues baseball team. Both were teenagers when they married.

When Lee performed in all-white nightclubs, Duncan sat in with the orchestra, pretending to be a musician, so he could see her perform.

The couple had a son, Frank III. In 1941, Frank III joined the Monarchs briefly as a pitcher, and the two Franks became what is believed to be the first father-son battery in professional baseball history. Later, both served in the Army during World War II.

Through it all, Lee remained in Kansas City, entertaining her fans with crowd favorites such as “I’ve Got a Crush on the Fuller Brush Man” and “Two Old Maids in a Folding Bed” — and with no dreams of national or international stardom.

By the time she died of a heart attack in her apartment on 28th Street in 1958, her career had fallen off. She was performing for tips and a small salary at the Hi-Ball Bar on 12th Street.

“One thing is certain about Julia Lee,” Tate wrote in his Second Line article: “She always loved Kansas City, the locally known Heart of America. In speaking of never wanting to leave her hometown, she said, ‘If you’re not happy, there’s no percentage in the big money.’”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.