KCQ Rapid Response: Swope Park Edition

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Kansas City Public Library Staff | LHistory@kclibrary.org

Spring has arrived, and winter-weary Kansas Citians have once again turned their attention to the great outdoors. The What’s Your KCQ? team, a collaboration between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, have been inundated with questions about the crown jewel of the KC Parks system: Swope Park. To keep readers satisfied, we’re taking on five inquiries for this week’s rapid response edition.

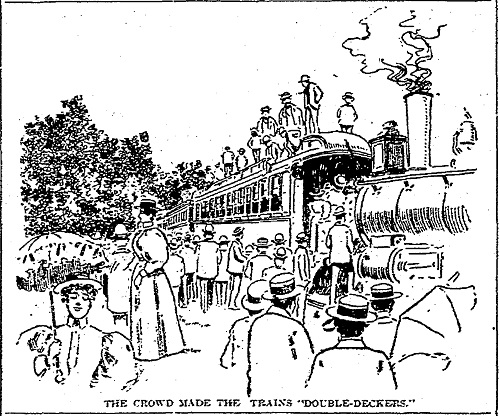

How was the opening of the park celebrated?

Planning for Swope Park’s opening began shortly after real estate tycoon Thomas H. Swope donated the land for the park to the city in 1896. When the park opened, The Star declared the event a “general jollification and jubilee,” and Mayor James M. Jones made the day a civic holiday.

On June 25 of that year, an estimated 18,000 Kansas Citians made the trip to the 1,805-acre green space by wagon, carriage, buggy, bicycle, and train. Free trains departed from 2nd and Wyandotte streets at 9 a.m. and departed every 25 minutes packed over capacity. By 10:15 a.m., one line alone had ferried over 4,000 passengers to the park. By 3 p.m., event organizers realized it would be impossible to get everyone who’d made the trip back to the city and suspended returning trains.

One Star reporter beheld the park and proclaimed, “Nature has written a poem across the county of Jackson.” He had seen revelers walking through the park’s lush, summertime landscape picking black-eyed susans and sumac, others casting lines in the Blue River, and still more picnicking and listening to hours’ worth of speeches celebrating Swope’s gift.

Swope himself took part in the celebration, but did so anonymously, wandering the park grounds and quietly enjoying the spectacle of so many happy parkgoers.

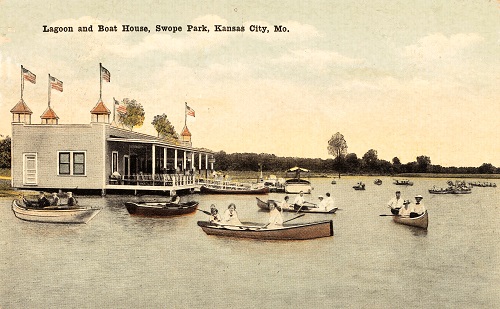

Were the lagoon and Lake of the Woods always there, or were they added when the park was created?

Historically, Swope Park has been a popular destination for summer water recreation. It has a swimming pool, lake, lagoon, and a section of the Blue River meandering through it that all seem natural. But did you know that just like the swimming pool, the lake and lagoon were both added to the land as new park amenities?

Landscape architect and Kansas City parks planner George Kessler chose a natural basin in the park for the site of Lake of the Woods. A dam constructed across a branch of the Blue River created a 15-acre wide, 35-foot-deep reservoir in 1908.

Work on the lagoon began the same year and was completed by spring 1910. Shortly after that, the addition of a boathouse drew visitors for boating and sailing, activities that were available until 1990 when park administrators decided to drain, dredge, and refill it to include in the zoo’s Africa exhibit.

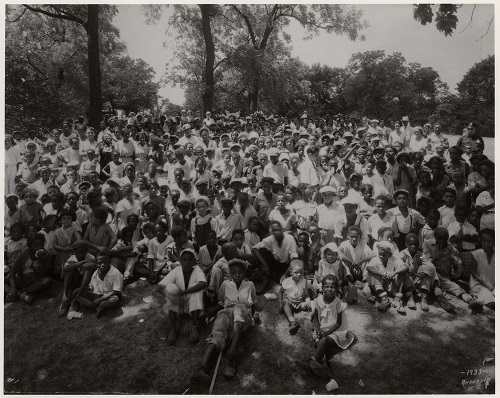

Was there really a place in the park called Watermelon Hill?

During Kansas City’s era of segregation, park rules dictated that Black residents could only gather at Shelter No. 5, located downwind of the zoo’s animal waste.

Shelter No. 5 and the surrounding area became known as “Watermelon Hill” — though the name was not used by park officials and rarely appeared in print. According to a presentation given by historian Joelouis Mattox in 2013, many Black residents refused to visit the park to avoid being associated with the racist stereotype.

Other Black Kansas Citians, however, hosted large gatherings at Watermelon Hill. Mattox said Black parkgoers helped create the name because they frequently served watermelons iced in large tubs. Gatherings occasionally exceeded 1,000 people and provided Black Kansas Citians with a recreational space for barbeques, dominos, kite flying, and other picnic festivities.

In 1954, the Swope Park pool was desegregated, and in 1963, the city council passed an ordinance outlawing racial discrimination in public facilities; the entirety of Swope Park was finally open to all for the first time in its history. And just as in the past, how Watermelon Hill is remembered today is a complex topic. Some view it as a cherished community gathering place, others as open mockery of Kansas City’s Black community and a throwback to its Jim Crow days.

What’s the history of the Swope Park Pool and will it be open this summer?

In 1940, the park board approved plans for a swimming pool, and the $400,000 aquatic complex opened to the public on July 30, 1942. In addition to three pools — one for swimming, one for wading, and one for diving — three adjacent sand beaches provided Kansas Citians, who were more accustomed to dips in the Blue River, a relaxing swimming experience. Over 5,000 attended the dedication of the swimming facility, described by city officials as the “finest and most modern” of its kind in the country.

But not all were welcome. In 1951, three Black Kansas Citians denied entrance to the pool filed a discrimination lawsuit in U.S. District Court. The city’s defense drew upon the Jim Crow era “separate but equal” doctrine, stating that much smaller pools in Nelson C. Crews Square and Parade Park that were open to Black residents met the threshold of equal treatment.

The judge overseeing the case disagreed, ordering that the new pool open its gates to all in 1952. The city appealed the decision, and rather than comply with the mandate, closed the pool until a final decision could be reached.

In 1953, the appeals court agreed with the initial decision, but officials kept the pool closed hoping the highest court in the land would side with the city. Finally, in 1954, the U.S Supreme Court refused to hear the case, and in June of that year, the Swope Park pool was opened to all for the first time.

Like most public facilities, the Swope pool closed in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It briefly opened for summer 2021 but closed again in July of that year for maintenance concerns. In 2022, KC Parks announced that the pool will remain indefinitely closed while the feasibility of repair is evaluated.

When did Swope Park host the first Ethnic Enrichment Festival?

As part of Kansas City’s celebration of the U.S. bicentennial, the Ethnic Heritage Committee hosted the first Ethnic Enrichment Festival in 1976. The committee organized the event through 1979, presenting ethnic menus at local restaurants and an Ethnic Bicentennial Parade.

Then, in 1980, inventor and entrepreneur Marion Trozzolo and Madalyne Brock from the city’s Naturalization Council took the event to the next level by forming the Ethnic Enrichment Council. The council put on its first festival on June 1 of that year at the Liberty Memorial. Several thousand people attended the event, which featured five booths, two stages, and representatives from 22 countries. Members of Rose Marie’s Fiesta Mexicana performed and have been an annual feature since.

The success of this event led to the creation of the Mayor’s Ethnic Enrichment Commission. From 1981 until 1983, the commission held the festival in Washington Square Park, until attendance outgrew the site. The event has been held in Swope Park since 1984.

Kansas City's Ethnic Enrichment Festival has grown to become one of the largest of its kind and the longest-running ethnic festival in the Midwest. Now, booths represent over 50 nations, and thousands of visitors come to sample ethnic foods and enjoy music and dance performances.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.