KCQ goes to school: Whatever happened to that old college in suburban Kansas City?

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Dan Kelly

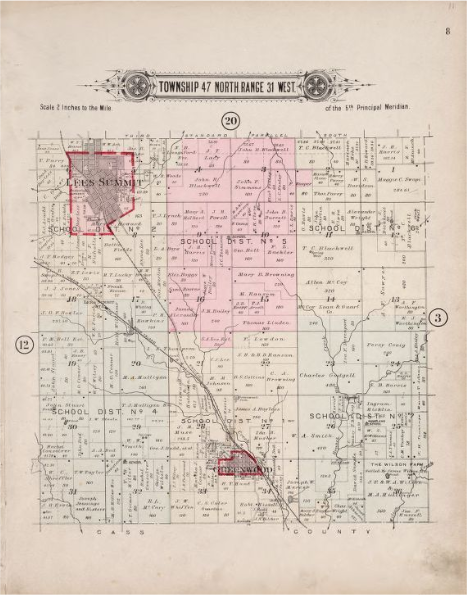

Greenwood, the suburban burg of about 5,200 residents just south of Lee’s Summit, has a sleepy downtown consisting of a smattering of small, old buildings, many of which serve as antique stores.

It’s the kind of place you take your favorite aunt for an afternoon outing.

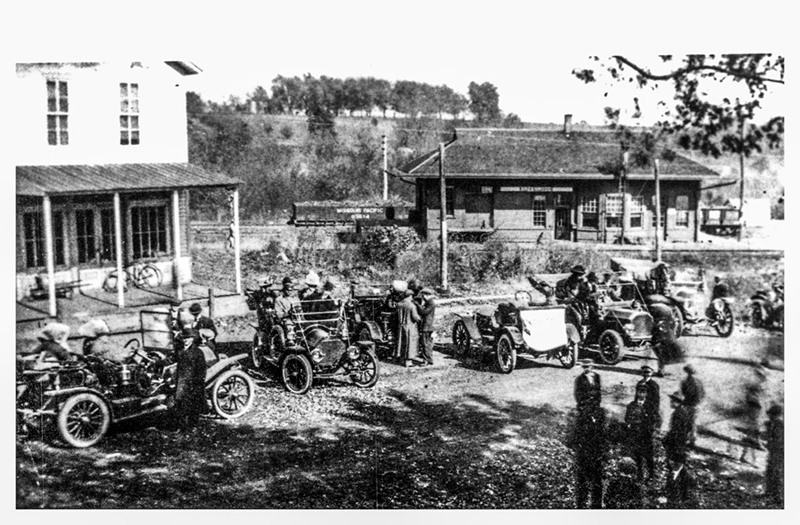

But 150 years ago, Greenwood was a hopping town, with depots and stockyards for two railroads, plus dairies, cider mills and woolen mills. It also was a college town.

That is the genesis of reader Jim Summers’ submission to “What’s your KCQ?,” an ongoing series in which The Star and the Kansas City Public Library partner to answer readers’ queries about our region.

Summers, a real-estate appraiser, wrote of his encounter about 45 years ago with an elderly acquaintance. The man told him that after the Civil War there was a women’s college in Greenwood that “had lasted only for a short time before a big fire.”

His question: “Was there such a college? Where did the girls come from, what did they expect from college and where did they go afterwards? What was the purpose and mission of the college?”

This appears to be an example of the unreliability of old memories — kernels of truth become muddled amid misinformation over the passage of time.

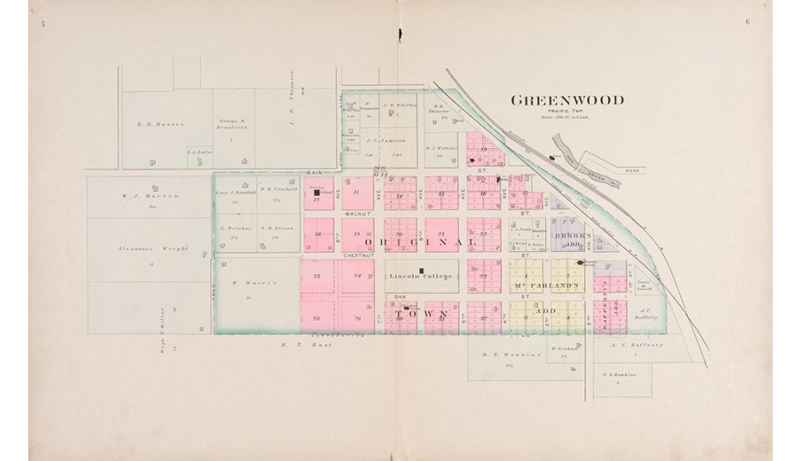

A college did indeed operate in Greenwood after the Civil War. Lincoln College, sponsored by the United Presbyterian Church, stood at Sixth Avenue and Chestnut Street. It was established in 1870 by the Rev. Randall Ross, an ex-Army chaplain from Ohio, on a five-acre tract donated by the town. This according to a history of Greenwood by Arnie Diaz on the town’s website.

Lincoln College was not, however, just for women. Nor was it destroyed by a fire.

But the confused memories are understandable.

The college closed in 1884, and the site experienced a later fire. Diaz’s history says, “The college and grounds were bought by W.A. Smith, who razed the college and built three small cottages on the west side with the lumber. On the east, he built a beautiful new home, which burned several years later.”

As for the recollection that the college was all-women, the story of Rose A. McCullough perhaps provides the explanation.

Given that her saga is almost the only enduring written memory of Lincoln College, it’s possible that our elderly gentleman with the original muddled memories simply assumed Lincoln was a women’s college.

At a time in U.S. history when it was very rare for women to attend college, much less a co-educational one, Rose A. McCullough was the only woman — along with four men — in the first graduating class of Lincoln College. And while her four classmates were lost to history, McCullough became something of an international hero.

She served as a missionary at Gujranwala in the Punjab province of what was then British-ruled India (now independent Pakistan) for more than 55 years, starting in November 1879. She returned to Greenwood in 1935.

A Star story in 1940 marking her 90th birthday said, “Miss McCullough was the first woman missionary to go into native villages and live under primitive hardships to carry on the evangelistic program.” King George V of Great Britain awarded her the Kaisar-I-Hind medal for outstanding public service.

Upon returning from Gujranwala, which named a street that passed her home “McCullough Road,” she apparently suffered from culture shock.

“After more than a half a century of living on the other side of the world I come back to my beloved America to find it a nation that seems to have forgotten God, the Bible, the Christ, the church,” she said in an interview with The Star in 1937. “The morals of the times of my youth and young womanhood in this country seem to have been overwhelmed by a tidal was of selfishness, Godlessness and immorality.”

The former missionary complained about women “exhibiting themselves wherever there is a bathing beach” and said “saloons are everywhere, and America even has women bartenders.”

McCullough, who had learned to speak in three dialects in India and traveled between villages in a “two-wheeled English dog cart,” also witnessed the rise of Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi.

“We missionaries hoped that he would become a Christian,” she said. “Had he done so he would have exerted a great influence.”

As it was, Gandhi merely became one of the world’s most important figures of the 20th century.

But back to Lincoln College.

According to “The Cyclopedia of Education: A Dictionary of Information for the Use of Teachers, School Officers, Parents, and Others,” published in 1876, Lincoln boasted five instructors and 75 students during the 1875-76 school year and tuition was $30 a year.

An advertisement in an 1876 edition of the Daily Journal of Commerce of Kansas City read: “A full course of instruction given in English, Mathematical, Scientific, and Classical Studies, by experienced teachers. Open to both sexes on the same terms. Boarding in private families, with lodging, for $3.00 to $3.50 per week.”

And an 1881 syllabus indicated that among the subjects taught to freshmen were Virgil, Greek Grammar, Cicero’s Orations and Elocution. Students could look forward to Latin, Algebra, Plane Trigonometry, Horace’s Satires, Hebrew and more during their ensuing years.

Unfortunately, for most students, Horace’s Satires would have to wait. Greenwood’s little college went out of business within three years.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.