KC Q - There’s a Dallas in Missouri?

What’s your KC Q is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Kate Hill

You won’t find Dallas, Missouri, on a current map. It’s no longer incorporated and, even when it was, the small settlement on the banks of Indian Creek near 103rd Street and State Line Road was better known by its most prominent landmark: Watts Mill.

Retired businessman Jere Hanney was already familiar with the general background of Dallas and Watts Mill but looked to flesh out the story. He asked KCQ, “What else do we know about it?”

Watts in a Name?

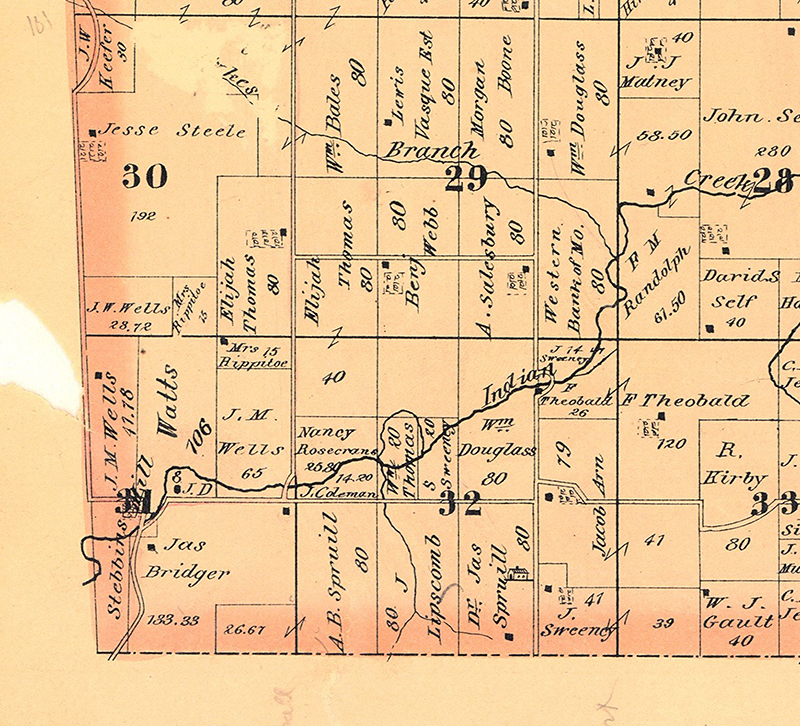

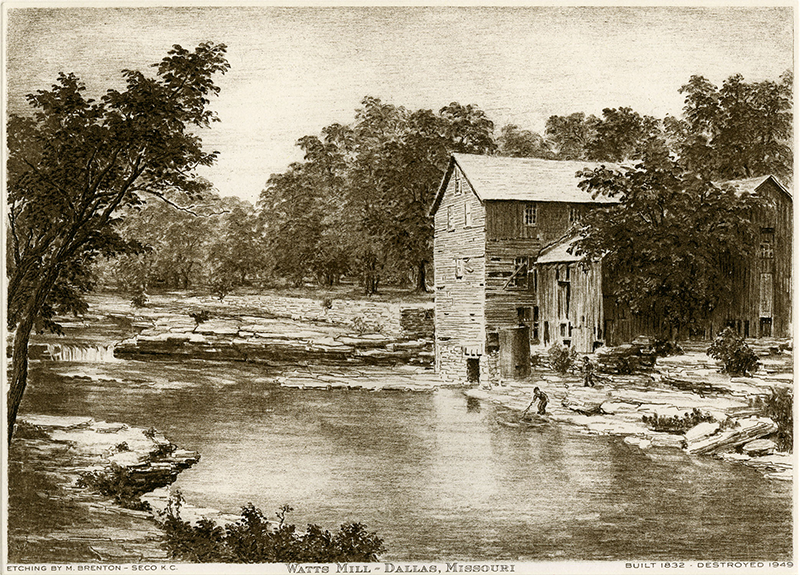

Before it was called Dallas or Watts, the area took its name from brothers George and John Fitzhugh, who purchased the land and built the original mill on Indian Creek in the 1830s. (Most sources date the mill to 1832, though others argue it was built in 1830 or 1838.)

Fitzhugh’s Mill was just east of the Kansas border, which at the time was also the western border of the United States. It became a popular rendezvous spot for traders and emigrants heading west on the trails. Travelers could rest, meet up with companions coming from Independence, Westport, or some other jumping off point, and even use the mill to grind wheat or corn before setting off on their journey.

Ownership of the mill changed hands a few times in the 1840s. In 1850, it was bought by Anthony B. Watts, who added on to the building and expanded it into a commercial enterprise that would last for three generations. His son, Stubbins, took over operations after his death. In his later years, Stubbins became a kind of local celebrity, known for his long white beard, proficient fiddling skills, and legendary storytelling. He died in 1922 at the age of 83.

Stubbins Watts was succeeded by his son Edgar, who ran the mill until it closed in the late 1930s. In 1942, he donated nine tons of its metal machinery to a World War II scrap drive. The property was sold in 1947 and the building torn down in 1949.

More than a Mill

But there was more to Dallas than the mill. It was also the home of James “Jim” Bridger, intrepid mountain man, scout, guide, and trader. Among his many achievements, he was credited with discovering the Great Salt Lake in Utah in 1824. Bridger retired to Missouri after his western adventures, settling on the farm directly south of Watts Mill. Upon his death in 1881 at the age of 77, Bridger was buried in the original Watts family cemetery (though his body was moved to Mt. Washington Cemetery in Independence in 1904).

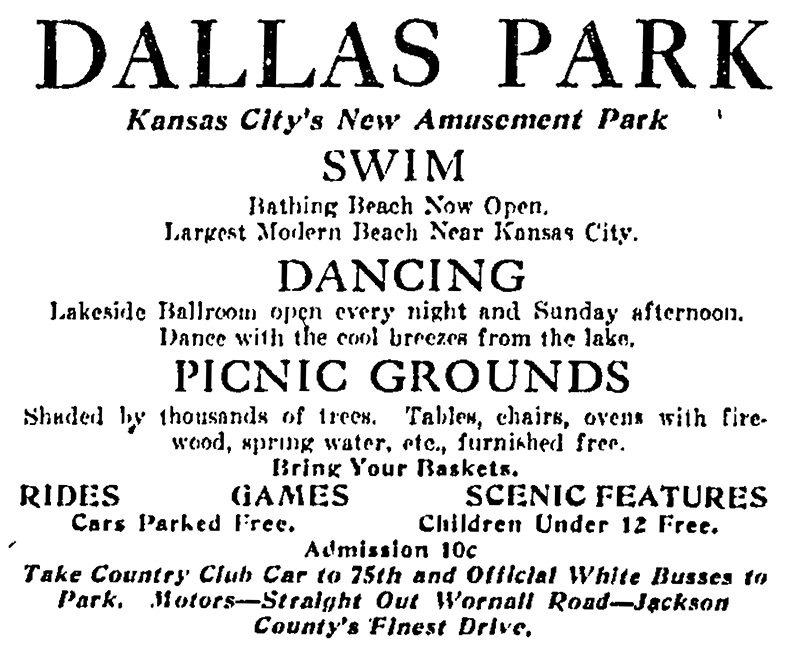

In addition to its famous resident, the town boasted a post office, several businesses, schools, and homes. In the 1920s, Dallas became a bit of a destination spot for Kansas Citians when the new entertainment hub, Dallas Park, opened. A May 26, 1922, article in The Kansas City Star detailed the features of the new park, including a lake for swimming and boating, overlooked by a dance pavilion. Additional attractions ranged from children’s swings and a merry-go-round to picnic tables, outdoor ovens, tennis courts, baseball fields, and a restaurant. The park was to open on Memorial Day of that year. Sadly, the lake’s bathing beach wouldn’t be ready for another month.

Just a short bus ride from the streetcar line and featuring free parking, Dallas Park quickly became a popular attraction for area residents. Newspaper articles and advertisements promoted church, business, and political picnics during the day, and other events in the evening. Within a few years, the dance pavilion had been converted into an enclosed dance hall, and a casino and “chicken dinner farm” had been added to the property. A rotating list of bands, including Bennie Moten’s Victor Recording Orchestra, entertained diners and dancers nightly.

It’s not clear how long Dallas Park played a role in Kansas City night life. In 1925 and 1926, during Prohibition, the Star reported on police raids and arrests at the park for alcohol possession. After a fire in early December 1925, an article in the Star noted that, “many complaints had been made by neighbors who declared the place was a public disgrace.” The reporter wrote that the park’s rural neighbors didn’t appreciate the business and speculated on the motive behind the slashing of every tire – including spares – on 30 cars in the parking lot a few weeks earlier. Sheriff’s deputies had watched the park ever since because it was such a “ ’hip-pocket’ night place.”

Whether due to the park’s rough reputation or in spite of it, newspaper advertisements and articles tapered off in the early 1930s. Families might have continued to picnic there during the day, but when the nighttime dance hall and casino closed is unknown.

Times Change

On January 1, 1958, Dallas was officially annexed into Kansas City, Missouri. The southern city limits were extended from 85th Street to 115th, between State Line Road and a jagged line to Blue Ridge Boulevard. The move expanded Kansas City by about 14,000 residents and 13.8 square miles. Thirteen years later, the Watts Mill name was resurrected with the construction of the shopping center at State Line and 103rd Street. The center opened for business in December 1971.

Efforts were made to resurrect the actual mill in the mid-1980s. Members of the Historical Society of New Santa Fe began petitioning and fundraising to reconstruct the building and designate the area as a city park. While the site did become a park, the rebuilding campaign stalled in the early 1990s due to a lack of city funding and interest. Part of the foundation is all that remains of the original Watts (and Fitzhugh) Mill.

How We Found It

Information on Watts Mill and Dallas, Missouri was found by consulting databases, newspapers, maps, and vertical files in Missouri Valley Special Collections at the Central Library. Ronald Becher’s manuscript, “Notes on Fitzhugh’s/Watts’ Mill”, provided detailed information about the mill’s history and an image of the ruins. Additional images were found in MVSC’s collections. The photograph of the Bennie Moten Victor Recording Orchestra is from the Goin’ to Kansas City Collection courtesy of Charles Goodwin and the Kansas City Museum and used with permission.