KC Q - Kansas City's Downtown Loop

What’s your KC Q is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

Written by Michael Wells

Reader Tom Decock was curious about how the interstate highway system was incorporated into Kansas City’s urban landscape. With the Downtown Loop nearing its 50th anniversary in 2022, now is a good time for KCQ to investigate.

While easy to criticize the Loop, it’s also difficult to imagine how we’d get along without it. It’s only about four miles in length but occupies more than 100 blocks of downtown real estate. So how did we end up with this much maligned, frequently used bit of infrastructure?

The story goes that President Eisenhower fell in love with the German Autobahn during World War II and brought the idea home.

But there’s a whole lot more to it.

Demand for better roads predates the Eisenhower years by a country mile. Organized advocacy for new road construction arose from an unlikely source, bicycle enthusiasts. Clubs like the League of American Wheelmen sprang up to support the new fad, with Kansas City cyclists organizing their own chapter by the 1890s.

By the turn of the century, automobile enthusiasts joined the fight and it wasn’t long before cyclists were pushed aside. These early motorists helped get the Federal Aid Road Act passed in 1916, and work on the first system of U.S. highways began once the money started flowing.

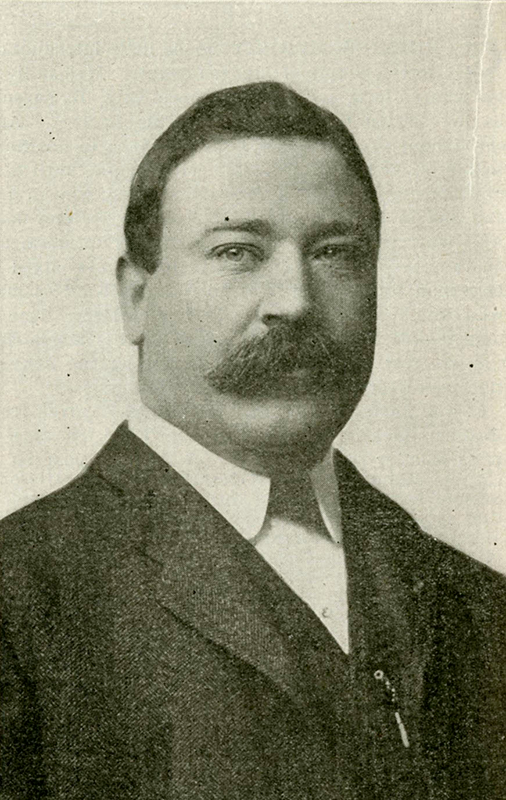

Enter (unsurprisingly) Boss Tom Pendergast, who gained appointment as superintendent of streets in 1900 and came to understand that voters often cared more about well-maintained streets than what went on behind the curtains of power. He and his formidable political machine helped elect a onetime downtown haberdasher named Harry S. Truman as presiding judge of Jackson County in 1922, and road improvements remained a top priority.

In 1931, despite the effects of the Great Depression, Pendergast urged voters to support a Ten-Year Plan allocating $50 million for public improvements. The money created jobs through the construction of new parks, sewers, waterways, public buildings and, of course, roads.

Meanwhile, the idea of building transcontinental routes was gaining traction.

Previous generations of highway planners thought that those highways should avoid urban areas, reasoning that the merging of long-distance and local traffic would create congestion. By the late 1930s, a new approach had taken root: Run the freeways right through cities, where congestion was attributed to short, daily trips made by locals and not the pass-throughs of long-distance travelers.

Pendergast had lost his grip on Kansas City – with political reformers hiring L.P. Cookingham as city manager – by the time an early plan for its Downtown Loop was written into the City Plan Commission’s 1943 report “Suggested Location of Inter-Regional Highways.” Beyond a lengthy verbal description of the route, it suggested passing the freeways through blighted areas that would be cheap to acquire. The highways, it said, could boost those areas economically. But it also warned of a potentially disastrous impact on already-prosperous areas.

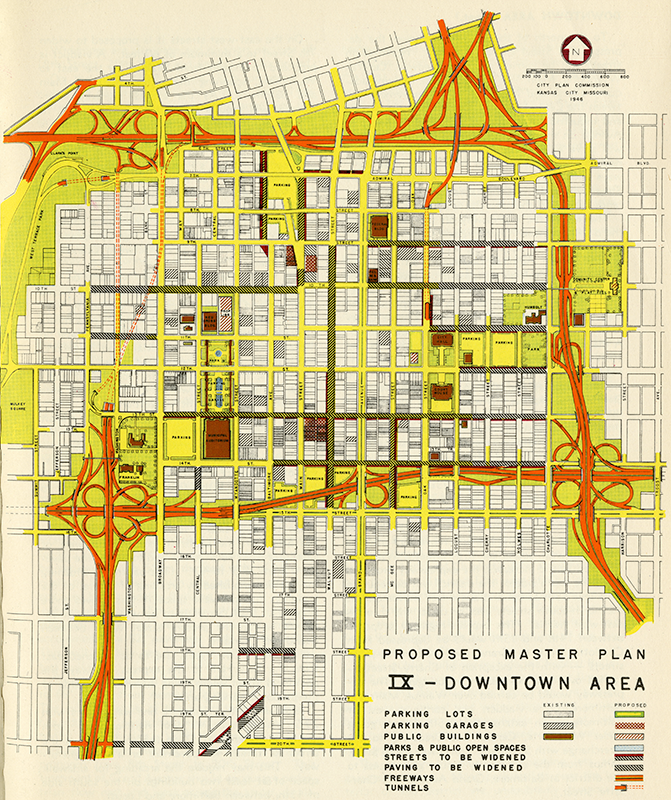

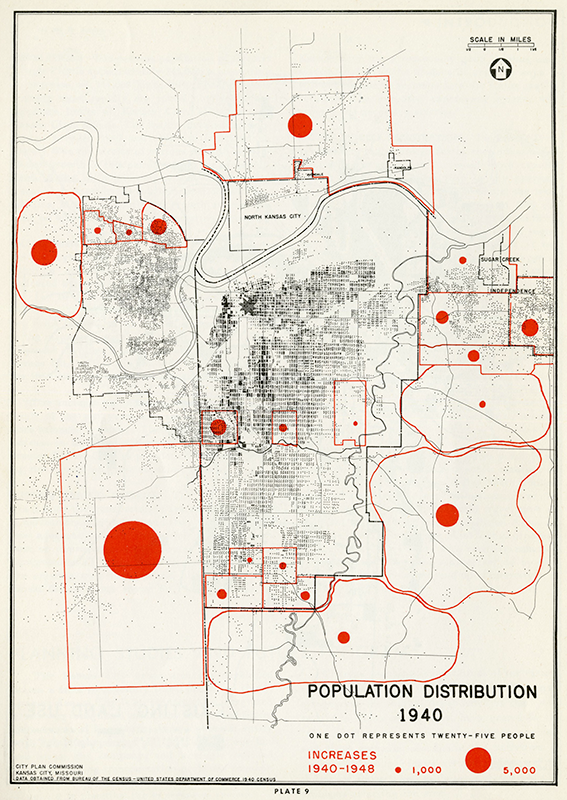

The idea of using blighted land for highway routes made its way into the city’s 1947 “Master Plan for Kansas City,” which encompassed residential development, public transit, schools, parks, and public buildings and was designed to catapult the city into the modern world. It was here that Kansas Citians were given their first glimpse of the Loop.

The urban renewal era got things rolling. In 1949, President Truman signed the American Housing Act, giving cities enhanced powers of eminent domain to clear blighted buildings and replace them with federally funded housing units. Later legislation expanded the bill’s scope, allowing blighted areas to be redeveloped for purposes beyond housing.

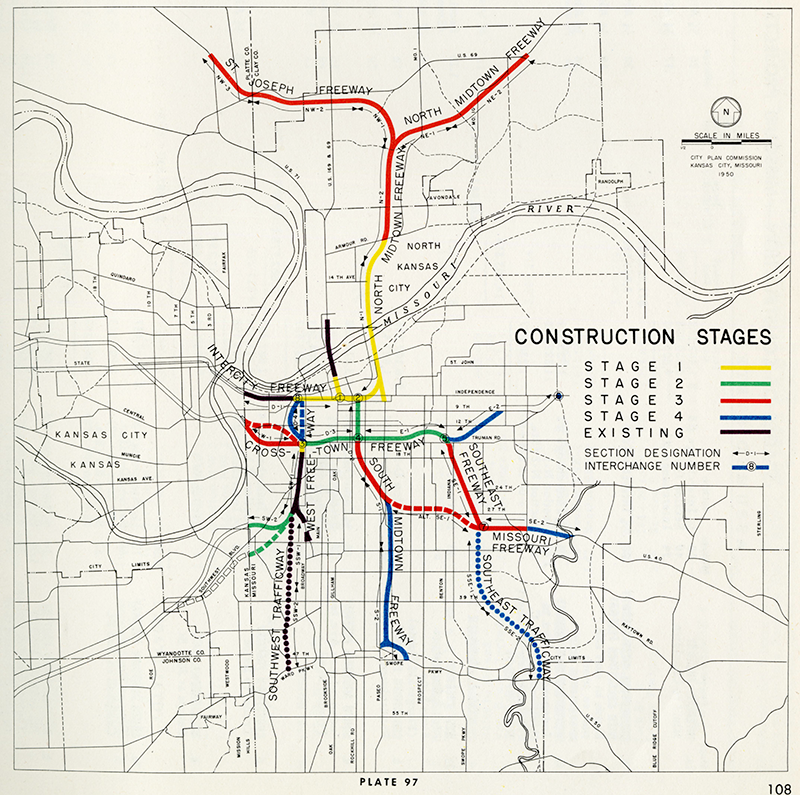

Funding for expressway construction still wasn’t in place by the time Cookinham published “Expressways of Greater Kansas City” in 1951, but that wasn’t about to curb his plans. Kansas City had a long history as an agricultural, livestock and business hub, and the 1951 report aimed to preserve that legacy through the new freeway system. Surrounding downtown with freeways surely would prevent businesses from flocking to the suburbs.

The report also noted the 1950s shift in residential population to the suburbs. Cookinham knew new suburbanites would need high-speed roads to get them in and out of the city as efficiently as possible.

The city manager also began aggressively annexing unincorporated land south and north of the river to retain taxpayers who were moving. With that came greater city control over the area’s expressway system.

In 1956, with Eisenhower’s signing of the Federal Aid Highway Act, city planners anticipated modest funding for road construction and suggested appropriately modest building schedules. They were way off. The new law created the Highway Trust Fund, which promised to cover 90% of highway construction costs.

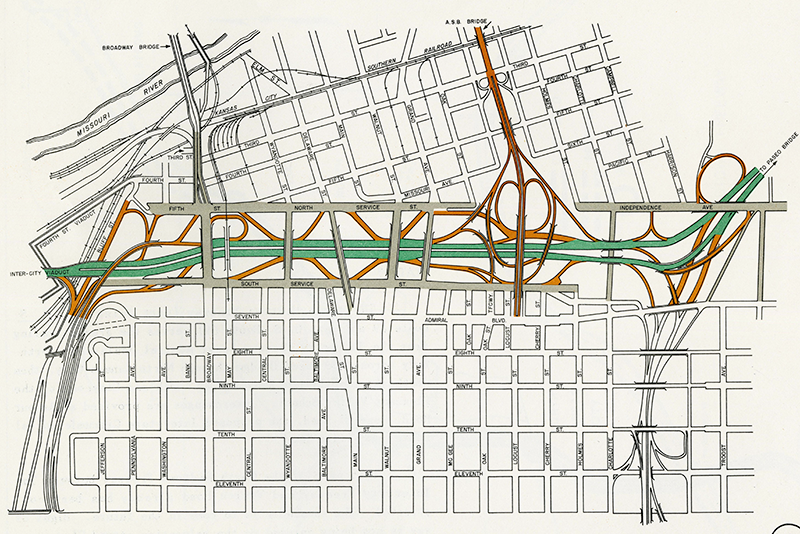

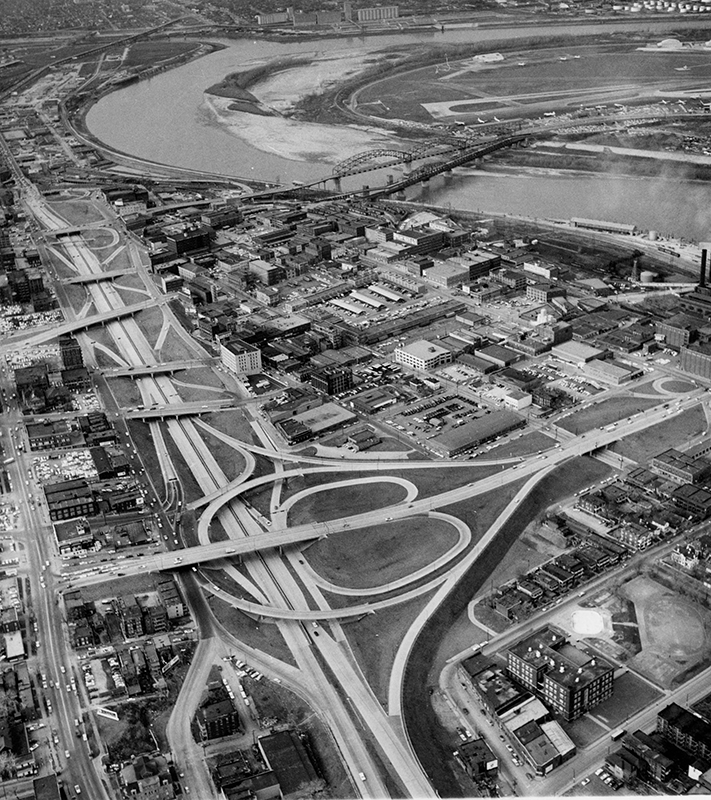

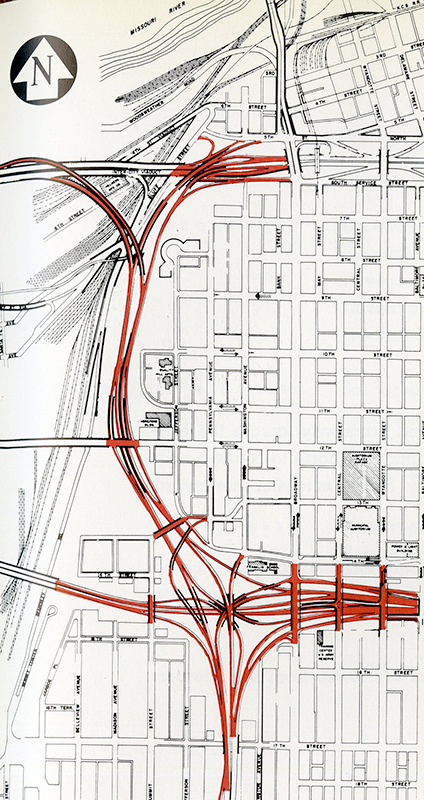

Construction of the Downtown Loop’s northern stretch had gotten underway in 1953. The area around Sixth Street between downtown and the River Market was cleared to connect the old Intercity Viaduct with the new Paseo Bridge to the east. The scope of the project, including the bulldozing of a large swatch of downtown buildings, brought it the nickname “The Kansas City Blitz.”

The Intercity Freeway was formally dedicated October 7, 1957, making national headlines. Setting off from the new Auditorium Plaza Garage at 12th and Central streets, Cookingham gave reporters and business dignitaries a grand tour of the city’s many urban renewal achievements. In true Kansas City fashion, they took in the downtown views from a flatbed trailer pulled by a farm tractor.

This distinguished hayride meandered to the new Paseo Bridge. Following speeches and a ribbon cutting, drivers now could zip across downtown with ease.

Not everyone celebrated. Muehlebach Hotel owner and Downtown Committee Chairman Barney Allis was outspoken in his criticism of the plan. He led a group of downtown business owners who believed the tightness of the Loop would make entering and exiting downtown streets difficult and dangerous. They also believed that motorists would bypass downtown, taking their dollars to suburban retail developments, rather than deal with a downtown traffic mess.

Construction of the eastern stretch of the Loop got underway in 1958. The Southeast Freeway, as it was called, would connect the Loop’s northeast corner to Interstate 70.

A few churches, homes and other historic structures survived the new construction and remain today as a testament to the once largely residential character of the area east of downtown.

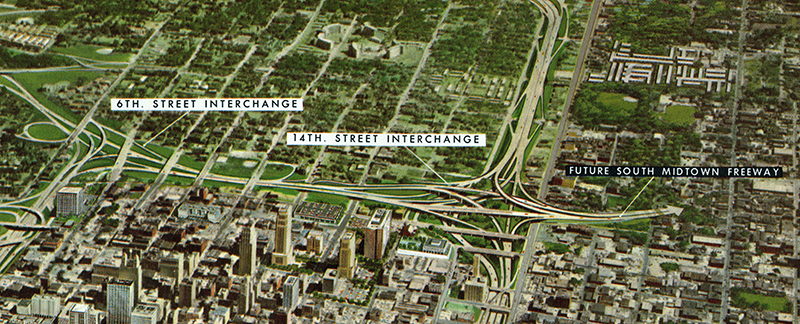

The eastern portion of the Loop was dedicated August 17, 1962. Mayor H. Roe Bartle led a ceremony featuring federal, state, and local dignitaries. The Air Force treated the crowd to a fighter jet’s sonic boom at an appointed time. The ribbon was cut, and traffic began flowing along the northern and eastern edges of downtown.

Interestingly, in the same issue of The Kansas City Star that covered the ceremony, readers could find a half-page ad encouraging them to use the new freeway to bypass the congested downtown shopping district for a new Sears location east of the city and boasting “acres of free store side parking.”

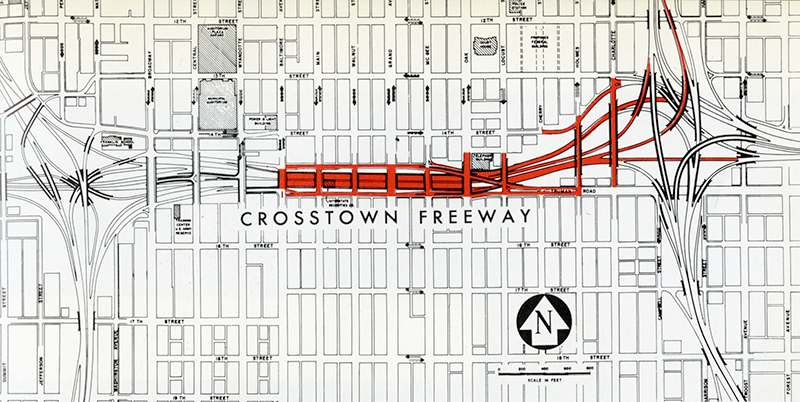

Work on the southern edge of the Loop began in 1961. If the initial portions of the Loop had been impressive, the fact that the Crosstown Freeway was planned as a depressed roadway cutting straight through the heart of downtown promised to make the project a monumental achievement.

Not only would land need to be acquired and cleared, but an eight-lane trench from Locust Street west to Broadway would have to be excavated before construction could begin. Locals labeled the project “the Kansas City Cut.”

The Crosstown Freeway was dedicated July 20, 1967, with a relatively modest ceremony featuring a brief speech by Missouri Highway Commission Chairman Jack Stapleton.

The Loop’s final section, the West Freeway, passed through the Kansas City’s west-side neighborhoods and sliced West Terrace Park, one of the city’s earliest George Kessler-designed achievements.

The project took nearly 20 years to complete and seemed to stir little excitement when it opened October 26, 1972. The Star noted that only Cookingham, the retired city manager, and highway engineer Joe Woolard were on hand. There was no formal ceremony.

Something in the city’s view of the Loop had changed over the decades. Part of it was construction fatigue. There was also criticism of the way it affected Kansas Citians’ relationship with downtown.

While freeways ease trips by car, they are often highly disruptive for pedestrians and cyclists. Over time, residents evacuated downtown and adjacent neighborhoods, leaving them to decay. Meanwhile, shoppers end entertainment seekers ignored the city center for decades, using the Loop to slingshot around it on their way to far-flung corners of the metro area. With the rise and proliferation of automobiles, miles and miles of streetcar and rail infrastructure fell into disrepair and were overlaid with asphalt.

Today, to many, the Downtown Loop is a construction and engineering marvel that helped bring Kansas City into the modern era. To others, it has wreaked havoc on our city’s urban core. The truth is perhaps somewhere in the middle. Like it or not, the Loop is ours to deal with. Pedestrians, residents, shoppers and transit users are once again inhabiting downtown. How they will affect its future remains to be seen.

How We Found It

For a general outline of interstate highway history, we used Earl Swift’s The Big Roads: The Untold Story of the Engineers, Visionaries, and Trailblazers Who Created the American Superhighways. Bill Gilbert’s This City, This Man: The Cookingham Era in Kansas City helped us learn about the career of L.P. Cookingham in the post-Pendergast years. Reports including Suggested Location of Inter-Regional Highways, The Master Plan for Kansas City, and Expressways of Greater Kansas City are available to researchers in the Missouri Valley Room on the fifth floor of the Central Library.

Read More

Read more about this and other KC Q answers with these great books from the Kansas City Public Library's Missouri Valley Special Collections.