KC Q - The Haunting of St. Mary’s Church

What’s your KC Q is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

Jason Dean, a parishioner at St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, wrote of hearing about a controversial priest who died in 1886 and haunts the church to this day. In conjunction What’s Your KC BOO?, our special Halloween edition of What’s Your KC Q focusing on Kansas City’s haunted lore, he asked us to investigate.

We found … intrigue.

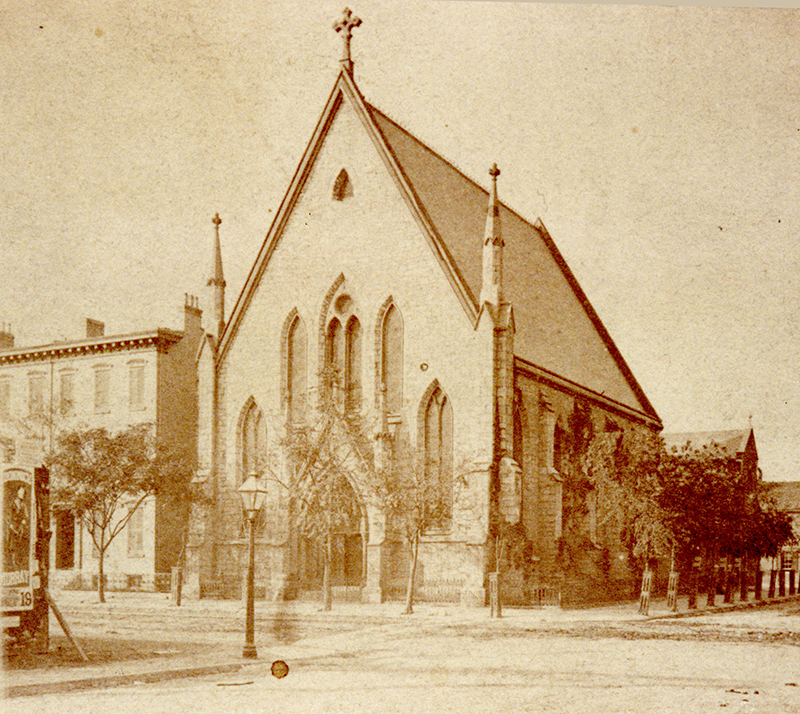

St. Mary’s wasn’t St. Mary’s when the church was first established in 1854. St. Luke’s Mission, as it was initially known, had humble beginnings. Lacking a permanent home, its congregation met at a variety of locations near today’s River Market neighborhood. The church prospered and, by 1867, had purchased a lot on the southeast corner of Eighth and Walnut and erected its first permanent home.

The young city was going through a period of rapid change. The opening of the Hannibal Bridge in 1869 established Kansas City as a rail hub connecting the American West to eastern markets. The livestock trade exploded in the West Bottoms, and the city began to rapidly expand in all directions. Expansion requires labor, and much of the heavy labor of carving out Kansas City from the rocky bluffs was provided by Irish immigrants.

Bernard Donnelly came to the U.S. from Ireland in the 1830s, eventually entering a Catholic seminary in St. Louis. He was ordained into the priesthood in 1845 and dispatched to Jackson County. From his base of operations in Quality Hill, Father Donnelly ministered to the Irish-Catholics settling in the West Bottoms. Recognizing that work was plentiful in the expanding city, he sent word back to Ireland to send additional manpower. The “hardy and laborious sons of Erin,” as historian C.C. Spalding referred to them, heeded the call, arriving in great numbers by the time of the 1870 census.

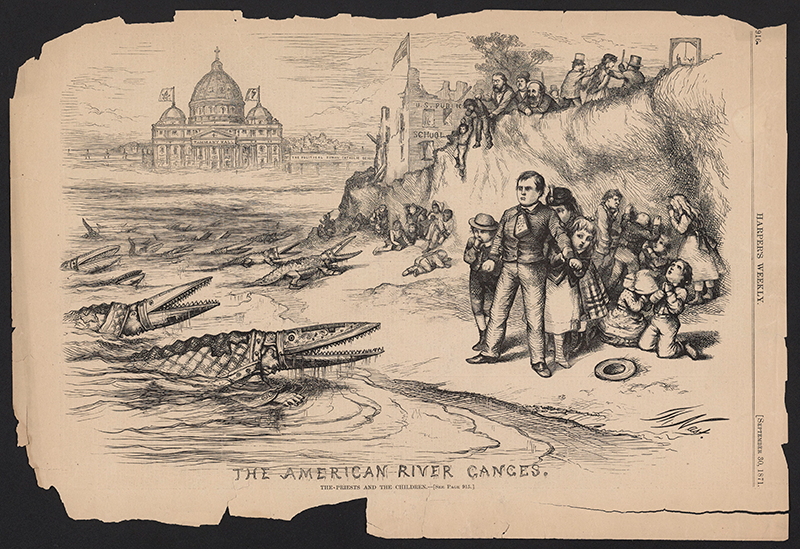

Changes in the ethnic makeup of the city did not go unopposed. Nativist organizations such as the Know-Nothing Party and the American Protective Association began springing up with a mission to protect Americans from foreign and Roman-Catholic influences.

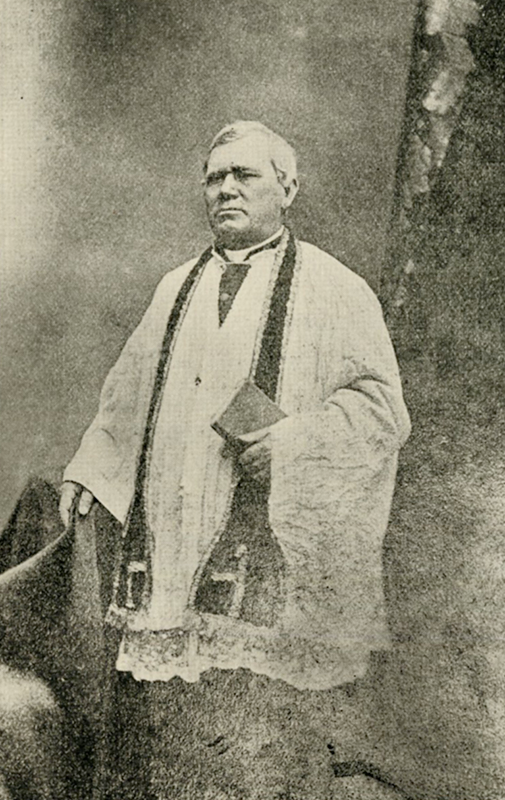

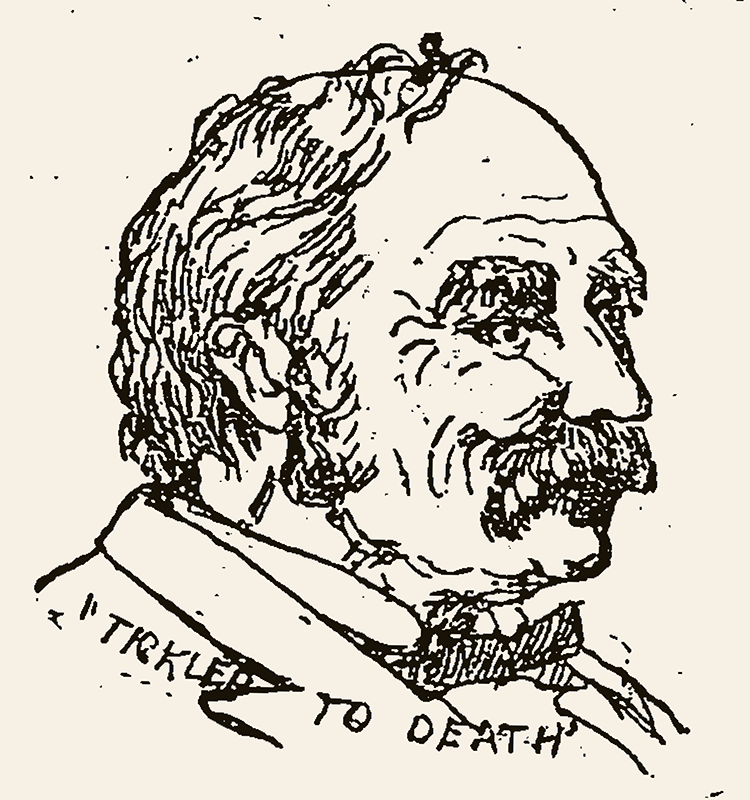

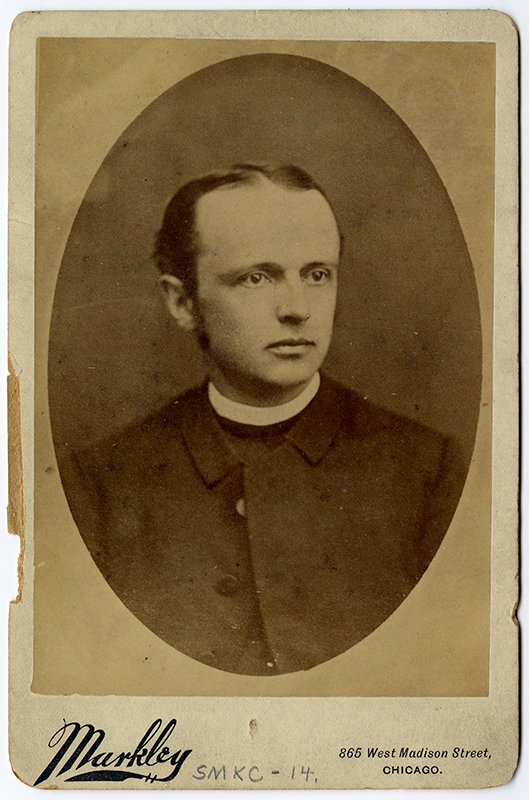

Amid that backlash came a young Protestant Episcopal priest, Henry D. Jardine, with an appreciation for his church’s Catholic roots and sensibilities. Appointed as rector of St. Luke’s Mission in 1879, he was among a segment of the Episcopal clergy advocating the church’s return to Catholic traditions – an Anglo-Catholic movement that, among other things, embraced the greater pomp and ceremony of Catholic services.

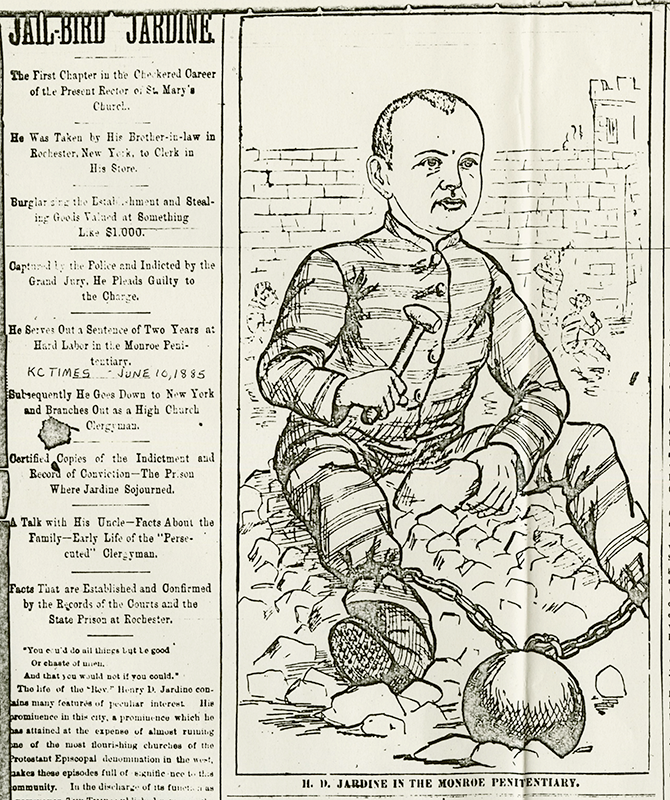

The details of Jardine’s early life are murky at best. Born in Canada around 1841, he was orphaned at a young age and raised by his older sister and her husband in Rochester, New York. It was there, while working in his brother-in-law’s trunk factory, that a 16-year-old Jardine helped a friend rob the business. Authorities connected the boys to the crime, and Jardine was convicted and sentenced to serve a two-year prison term. He found religion, was admitted to Trinity College in Connecticut, and there was introduced to the concept of Anglo-Catholicism.

He ultimately became an Episcopal priest in 1875 and had brief stay in St. Louis before finding his way to Kansas City.

One of Father Jardine’s first moves at St. Luke’s was changing the name of the church to St. Mary’s. It’s not known if that caused a stir, but the young priest quickly became a divisive character. Rarely seen in anything but a floor-length black cassock and clerical collar, he certainly would have struck the figure of a Roman Catholic priest. He introduced the high church rituals favored by the Anglo-Catholic movement, adding candles and incense and recruiting altar boys, and introduced the formal, Catholic-like confession of sins. It all created friction.

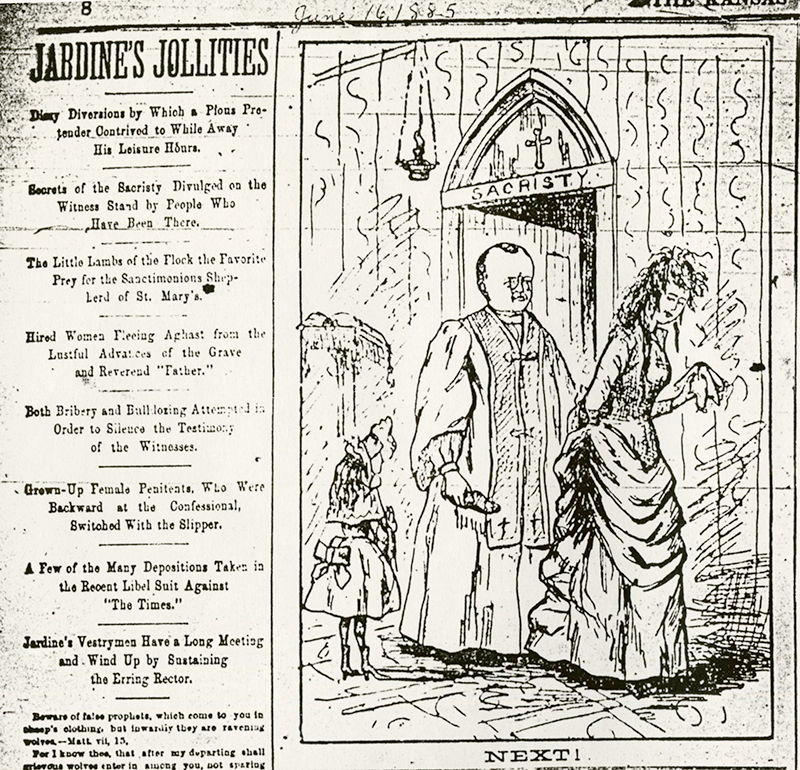

Adding to the controversy was Jardine’s reported popularity with female members of the church. At the same time, as one newspaper reporter noted, “among the men he had the faculty of arousing bitter antagonisms.” Be it because of that, anti-Catholic sentiment, or simply negative reaction to change, some parishioners left the church. John C. Shea, editor of The Kansas City Times, made his displeasure known in print.

Two events escalated tensions: the publication of a pamphlet attacking Jardine’s character and the excommunication of two members of the church for attending services while inebriated. When the charges in the pamphlet eventually found their way into Shea’s newspaper, he also was excommunicated.

The Times’ first article, headlined “Jail-Bird Jardine” ran June 10, 1885 and detailed the priest’s crime and prison sentence. Jardine was open about the episode, describing it as a youthful indiscretion for which he had paid his debt to society. Shea followed six days later with an article, “Jardine’s Jollities,” that levied new charges of immoral acts with parishioners, many during private confessions. In one case, the priest was said to have been caught spanking a young lady in a state of undress with a slipper as a form of penance. The newspaper re-labeled the church sacristy as Jardine’s “spankistry.”

The Times continued their assault while newspapers across the country reported on Jardine’s and Shea’s unseemly fight. British Parliament member and Irish nationalist T.P. O’Connor spoke on the priest’s behalf during a visit to Kansas City, and Jardine attempted to clear his name by bringing libel charges against Shea and The Times. The counts were dismissed, with the court citing Jardine’s inability to conclusively disprove the charges against him.

Would the polarizing priest return to lead services on Sunday? Doubts were quickly dispelled. Sprinkled among the worshipers at Mass that morning were the vestrymen of St. Mary’s, pistols at their sides. Some attendees spied members of St. Patrick’s Catholic Church in the crowd, showing solidarity against anti-Catholic forces. Father Jardine finally arrived in full Anglo-Catholic regalia, and led his usual high church service. He, too, wore a revolver.

The subject of his sermon: courage.

A new challenge was emerging, however. In response to the charges in The Times, an ecclesiastical court was convened at Grace Episcopal Church in September 1885. It took a little over a month to find Jardine guilty of inappropriate behavior with female parishioners and the habitual use of chloroform, a drug the priest was known to use to use to treat chronic pain from a nerve condition. He was to be removed from his priestly functions, though the verdict wouldn’t be announced immediately.

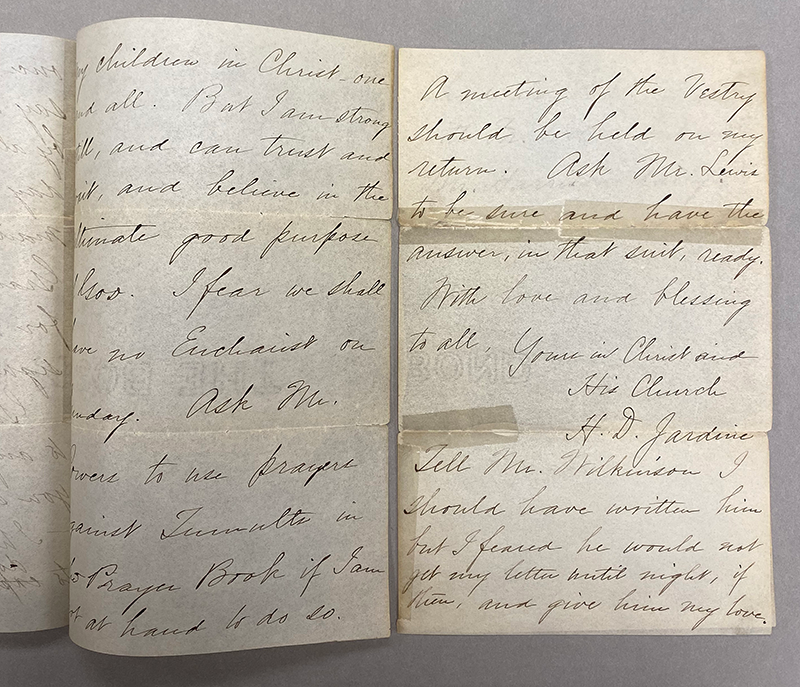

When a motion for retrial was swiftly denied, Jardine traveled to St. Louis on January 5, 1886, to appeal to the bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Missouri. Staying at Trinity Church as a guest of Father George C. Betts, Jardine got word that the ecclesiastical conviction would be announced back in Kansas City On January 9.

The next morning, Betts was preparing for the morning service at Trinity Church when he discovered Jardine apparently sleeping in the sacristy. When Betts attempted to wake him, he was horrified to discover that Jardine was dead, a handkerchief over his face and a small bottle of chloroform at his side. Around his waist was an old, rusty iron chain – welded together as a presumed act of eternal penance.

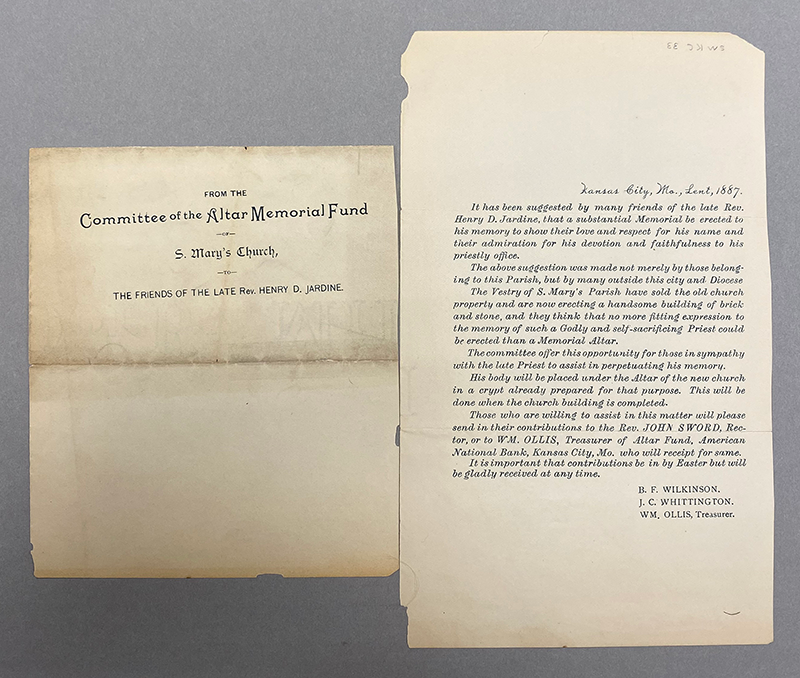

The earthly remains of Henry Jardine were returned to Kansas City on January 29. Braving bad weather, a large crowd of supporters and curious onlookers met the arriving train at Union Depot. The casket was transported to St. Mary’s Church and the upper half of the lid removed, revealing Jardine in his priestly cassock – and the penitential chain beside him. Mourners viewed the body throughout the day, a requiem Mass was held the next morning, and Jardine’s remains were taken to Union Cemetery for storage in its vault until burial could be arranged.

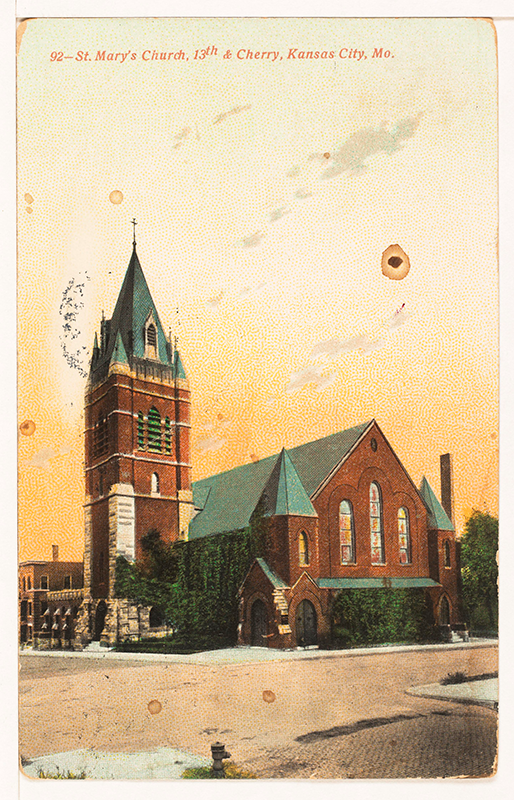

Despite the controversy, Jardine’s work in Kansas City had a lasting impact. He and the St. Mary’s congregation helped set up schools for downtown children and founded All Saints Hospital, the forerunner of today’s Saint Luke’s Health System. Jardine also was instrumental in obtaining land at 13th and Holmes for a new St. Mary’s Church, which he never saw completed.

Even in death, however, Jardine was a magnet for controversy. The press debated whether he died by accidental chloroform overdose or suicide. The medical examiner in St. Louis expressed doubt at the suicide claims. However, the Bishop ruled his death a suicide, and Jardine’s enemies saw the act as a final admission of guilt. Supporters noted the tremendous stress of the trial and its effect on the priest’s nerve condition, which they said led him – unintentionally – to administer the lethal dose. They also pointed to the last known letter he’d written, which made no hint at suicide or guilt but instead expressed his resolve to continue fighting.

There were questions, too, about what to do with the body. If Jardine had committed suicide, he could not be buried in consecrated ground and certainly not, as church leaders wanted, beneath the altar of the new church. His remains were quietly moved in 1890 to Elmwood Cemetery, remaining there until a few of his living supporters lobbied successfully to have them interred in the consecrated St. Luke’s Burial Ground at Forest Hill Cemetery in 1921. It was the standard resting place for the priests of St. Mary’s Church.

It still might not have brought him peace. Ghostly reports arose and persisted at St. Mary’s. Parishioners claim sensations of being watched as they pass through the building alone at night. They’ve said they detect the smell of incense like that used in Jardine’s high Mass services. There’s one account in the 1990s of a longtime church member stopping to check on something at night and, from the parking lot, seeing what appeared to be a floating figure on the church’s second floor. An investigation found the entrance to the floor locked but unexplained noises emanating from behind the door.

One church member decided to look further, arriving at the church one night with an electromagnetic field detector. According to this ghost hunter, the meter was calm while moving up the stairs but began “buzzing like an electric razor” as he neared the second floor. Later, as he neared the area of the altar once planned as Jardine’s final resting place, the meter sprang to life again. Photographs of the altar reportedly revealed a priestly figure carrying a candle.

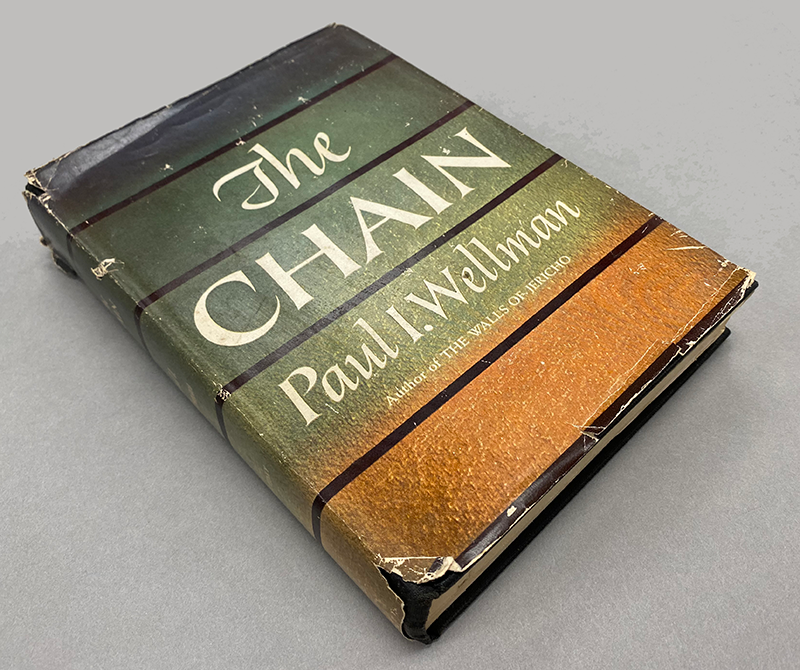

Believable or not, St. Mary’s began celebrating its ghost, viewing Jardine as a protective spirit. In 1949, Kansas City Star writer and novelist Paul I. Wellman incorporated the Jardine story in a fictional story, The Chain. Set in rural Kansas, it featured a young, idealistic priest who runs afoul of longstanding church members when he begins ministering to the town’s lower classes. Wellman writes: “An iron chain. Linked. Rough. Welded inescapably about the gaunt body. It was dark against the almost transparent whiteness of the skin, and brutally shocking in its implications. … Of his own volition he had endured, through all those hard years, the ever-twisting, ever-constricting reminder, his secret burden for that one mad act of his youth.”

St. Mary’s Church once stood in a bustling downtown neighborhood. Over time, however, it became a lonely, steepled brick structure in a landscape of urban renewal projects – an historic and, ahem, ghostly presence.

But like the legend of Father Jardine, the church endures, and members finally decided in 2000 to lay the late priest to rest as originally intended. Working to unearth his remains at Forest Hill Cemetery, a crew dug about 5 feet before encountering small pieces of wood and bits of window glass from the coffin. Next, workers found a small box that contained Jardine’s chain. And finally, they located his bones. The remains, and chain, were newly entombed beneath the altar dedicated to him at St. Mary’s.

There, many maintain, Jardine keeps everlasting (and sometimes noticeable) watch over his flock.

How We Found It

Much of the information for this article came from the St. Mary’s Episcopal Church Collection, housed in the Missouri Valley Special Collections at the Central Library. The array of records, correspondence, and photographs – dating the 1820s – was generously donated by the church to the Kansas City Public Library in 2014. Michael D. Frost’s The Short Histories of St. Mary’s and St. George’s Episcopal Churches also was a helpful reference. Information about the Irish experience in Kansas City came from Pat O’Neill’s From the Bottom Up: The Story of the Irish in Kansas City. Other images were found on the Kansas City Public Library’s digital history site kchistory.org.

Read More

Read more about this and other KC Q answers with these great books from the Kansas City Public Library's Missouri Valley Special Collections.