KC Q Dives Into Story of Leeds, Where Black Families Flourished in a 'Garden of Eden'

By Jeremy Drouin

A Tale of Two Leeds

Driving the stretch of Interstate 70 over the Blue River, a few minutes west of the Truman Sports Complex, the railroad tracks and warehouses to the south provide a glimpse of the industrial neighborhood of Leeds. An alternate route to the sports complex, along Stadium Drive, takes you to the heart of the district once considered a suburb of Kansas City. Former Leeds resident Christene Sharp reached out to "What’s Your KC Q?" to ask about the town’s history.

Driving the stretch of Interstate 70 over the Blue River, a few minutes west of the Truman Sports Complex, the railroad tracks and warehouses to the south provide a glimpse of the industrial neighborhood of Leeds. An alternate route to the sports complex, along Stadium Drive, takes you to the heart of the district once considered a suburb of Kansas City. Former Leeds resident Christene Sharp reached out to "What’s Your KC Q?" to ask about the town’s history.

She wrote: "I would love to know as much as possible about the history of the Leeds neighborhood. Some history on the founding and first businesses."

What’s Your KCQ is a series in which the Library and the Kansas City Star partner to answer reader questions about our region.

In this case, the library’s Missouri Valley Special Collections has numerous resources for researching neighborhood histories. In searching articles, photographs, maps, and other resources about Leeds, we discovered a once up-and-coming manufacturing suburb — home to a variety of industries — that later became an enclave for many in Kansas City’s African American community.

Rise of a Manufacturing Suburb

During Kansas City’s economic boom of the 1880s, investors began purchasing land in the Blue River Valley east of the city limits. In addition to the availability of miles of river frontage, the land was inexpensive, undeveloped and not subject to municipal taxes.

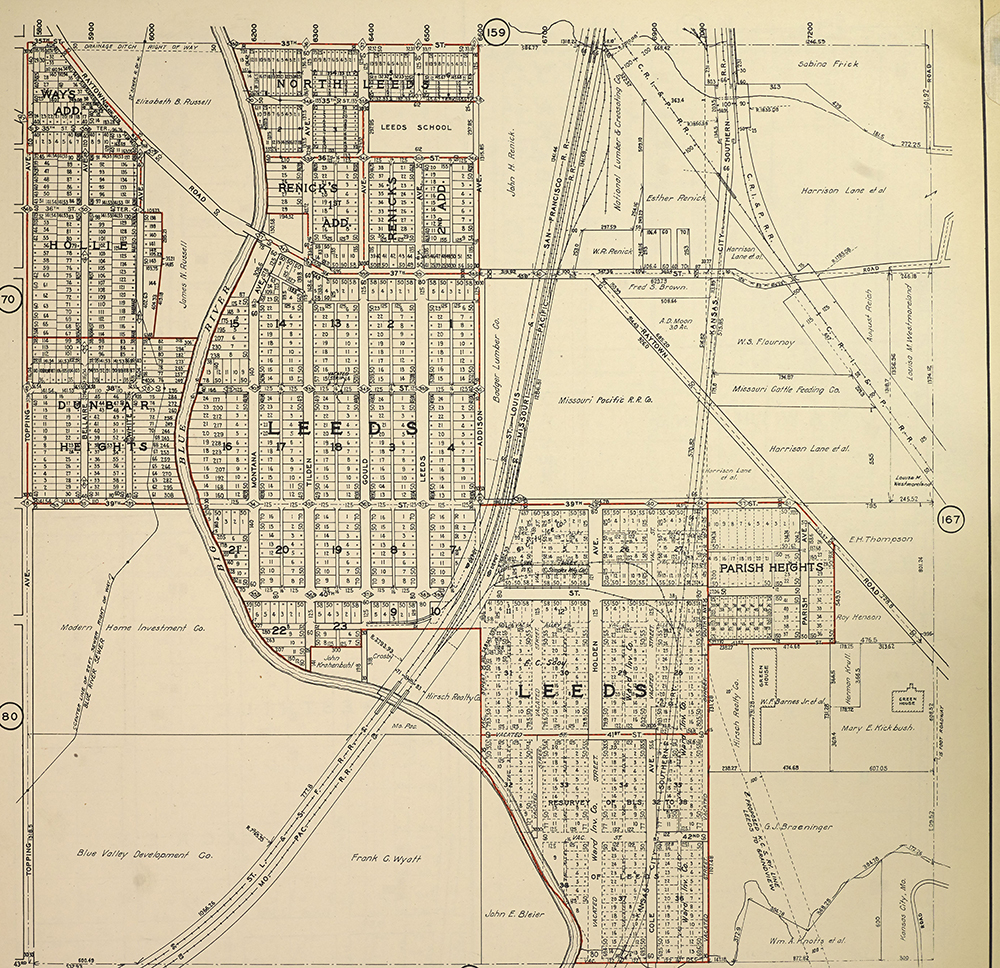

When railroad construction began in the valley in 1887, manufacturing soon followed. Residential districts sprung up nearby with housing for the growing number of factory workers in the area. The industrial town names of Manchester and Sheffield reflected the English capital used to develop them. Leeds was the newest and southernmost industrial district in the Blue River Valley, stretching from the Blue River east to Raytown Road and from 35th to 43rd streets. The first plat was filed by real estate developers John H. Lipscomb and Leander J. Talbot in 1889 (the latter a former one-term mayor of Kansas City and three-term city auditor).

Why the name Leeds? Neither Lipscomb nor Talbot appear to have had ties to English investment companies. Rather, they likely wanted to stay consistent with the borrowed English names of the neighboring suburbs.

Atlas of Kansas City, MO, and Environs, 1925, showing the Leeds Industrial District. Image: FIMo map database, Kansas City Public Library.

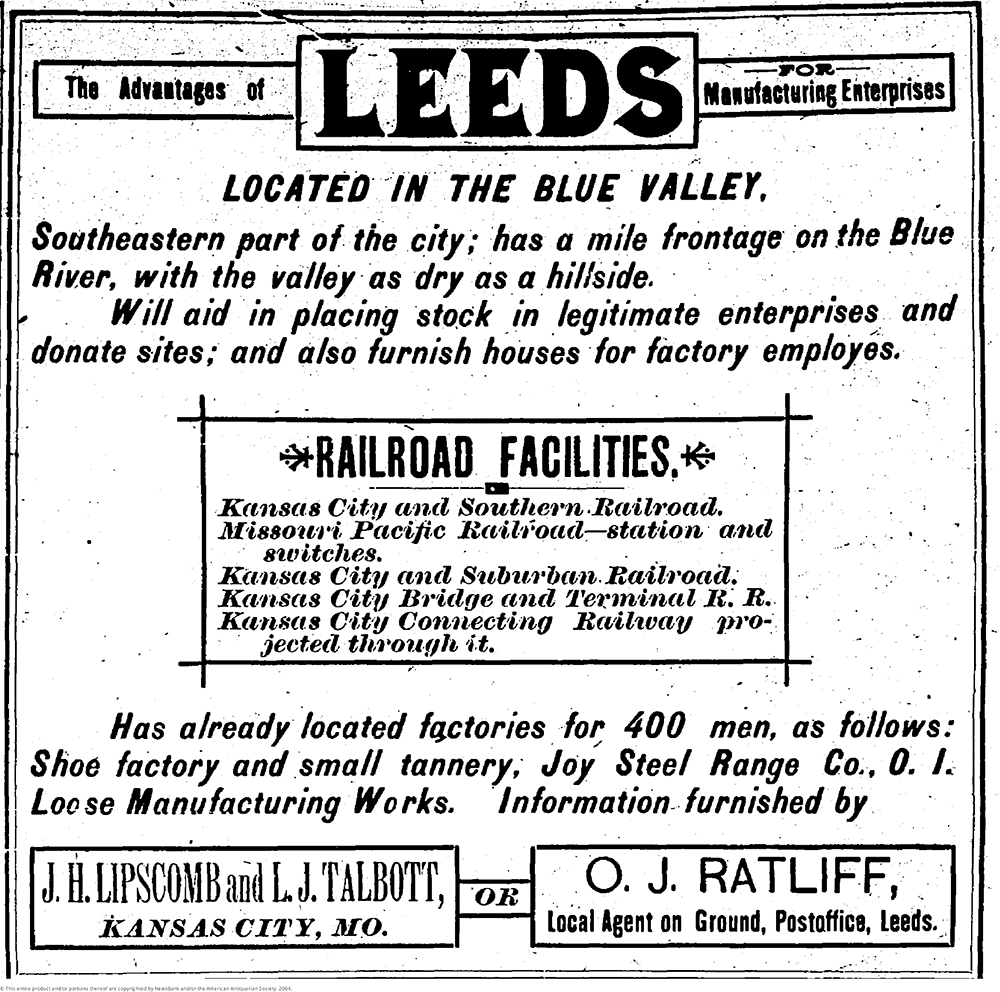

Another founder and early promoter of Leeds was real estate developer Odd J. “Jim” Ratliff, who was the town’s sole realtor and stood to gain financially from its growth and success. He, Lipscomb and Talbot began marketing the “new suburb” to potential investors in 1889. Advertisements in the morning Kansas City Times and evening Star touted Leeds as an ideal manufacturing location because of its available riverfront land, railroad facilities, and housing for workers. Lipscomb envisioned Leeds as a vast factory field and had dreams of converting the Blue River into a canal to accommodate barge traffic.

Leeds advertisement in the September 7, 1890, Kansas City Times.

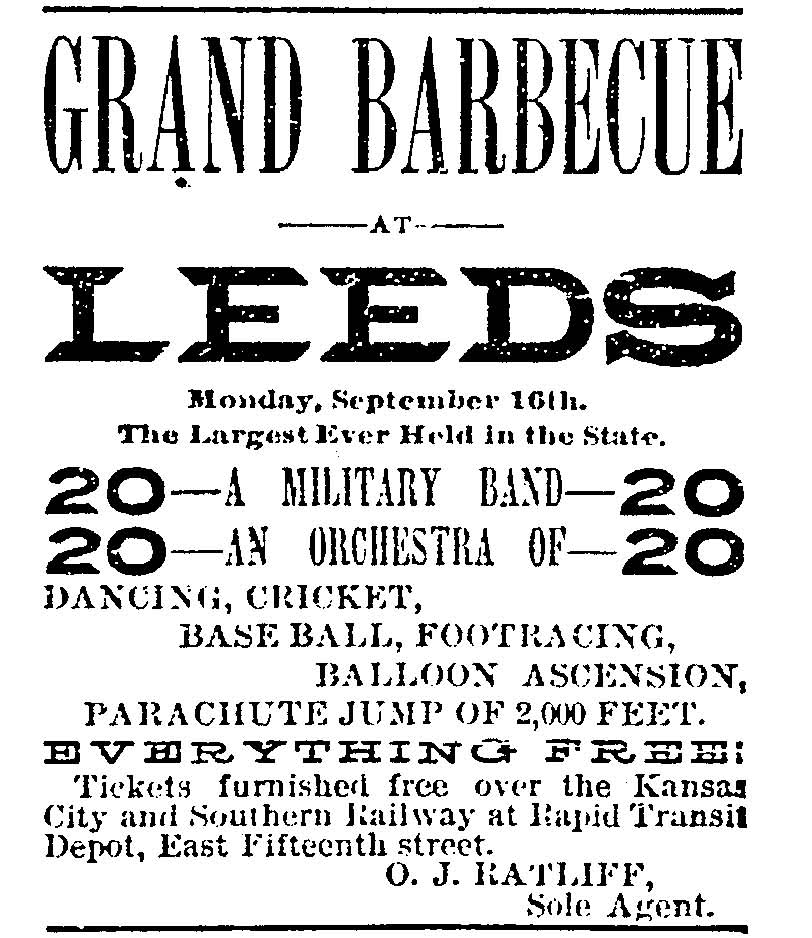

The entrepreneurs knew then what is still true today: If you want to get the attention of Kansas Citians, throw a barbecue. On September 16, 1889, the town of Leeds celebrated its founding with a “grand barbecue” and welcomed any and all to attend. The Kansas City and Southern Railway ran 12 free trains throughout the day to and from the suburb.

An estimated 2,000 people turned out for the gathering, which featured music, dancing, sporting activities and a hot air balloon ascension. Honored guests included Kansas City Mayor Joseph Davenport and two well-known former Confederate Army officers: Gen. Jo Shelby and Col. John T. Crisp. Each waxed eloquently to the crowd about the future prosperity of Leeds and its potential to become Kansas City’s largest suburb.

By all accounts, the barbecue was a great success. The Star reported the next day that many prospective residents were moved to purchase building lots on the spot.

Kansas City Times clipping, September 13, 1889.

Manufacturing jobs were plentiful for Leeds residents and conveniently located within walking distance. By the early 1900s, factories were producing shoes, stoves, linoleum, spirits, wool products, and a host of other goods.

Part of Leeds acquired telephone, water and electrical service after it was annexed by Kansas City in 1909. New businesses sprouted up along 37th Street (now Stadium Drive), the main corridor through town.

A 1917 photographic postcard of Leeds in the library’s special collections shows an unpaved 37th Street lined with telephone poles and several businesses — a horseshoeing shop, restaurant, saloon, and drugstore — along with a sign touting, "FOR SALE | ACRE TRACTS | FARMS to SUIT." The listed realtor was a familiar name: O.J. Ratliff.

Photo postcard looking north on 37th Street in Leeds, MO., dated 1917. Image: Mrs. Sam Ray Postcard Collection, Kansas City Public Library.

The town grew to include a post office branch, bank, police and fire stations, and two churches. In 1917, a four-room school was constructed at 36th Street and Fremont Avenue to accommodate a growing number of students. It was supposed to be a temporary location but remained the site of the Leeds School for the next four decades.

Leeds continued to prosper through the 1920s and attract new industries. In 1924, a 25-member Leeds Improvement Association was organized with the purpose of fostering community spirit by promoting industry and homebuilding. That same year, Leeds was chosen as a route for Kansas City’s inaugural bus line.

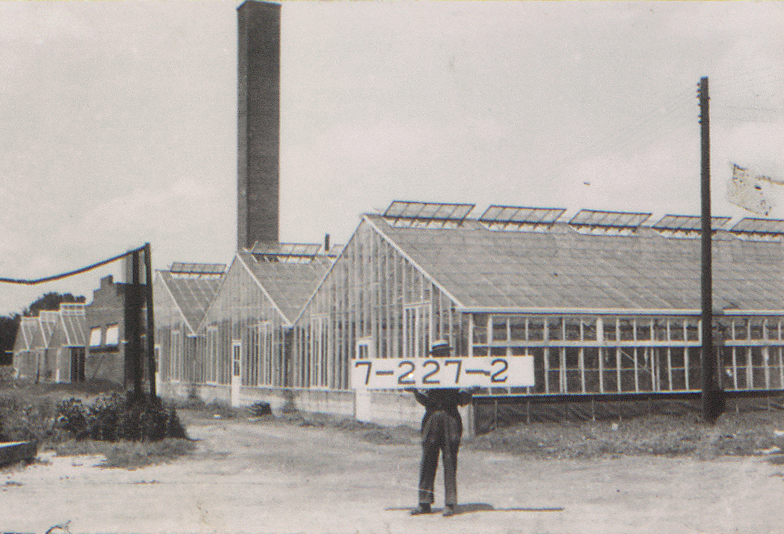

A 1926 report, Jackson County, Missouri: Its Opportunities and Resources, described Leeds as a "municipality within a municipality" with roughly 8,000 residents and lucrative employment opportunities at its many manufacturing plants and businesses. The area was highlighted as a gardening center. Leeds' 13 greenhouses produced approximately 90% of the flowers sold in Kansas City, including nearly 1 million roses harvested annually.

The district also boasted a railroad tie-treating plant, three quarries and two ice houses, plus coal, grain and lumber operations.

The Grover F. Renick Greenhouse near East 37th Street and Raytown Road. The Renicks were a prominent family and original landowners in the Leeds area. Grover’s father, William R. Renick, operated a general store there for more than 50 years and was the town’s postmaster for 35 years. Image: 1940 Tax Assessment Photograph Collection, Kansas City Public Library

Leeds Hospital

With tuberculosis cases on the rise in the early 1900s, city health officials saw need for a hospital. The remoteness of Leeds on the outskirts of the city limits made it an ideal site. A tent colony for patients was established until a permanent facility could be erected.

Construction of the Kansas City Tuberculosis Hospital, commonly referred to as Leeds Hospital, was completed in 1915. Much of the labor was provided by inmates from the adjacent Municipal Farm. The hospital could accommodate 150 patients. A 1929 expansion added beds and a separate wing to treat African Americans.

Kansas City Tuberculosis Hospital at what is now Raytown Road and Eastern Avenue, west of the Truman Sports Complex, circa 1940s. The hospital closed in 1964, and the building was razed in 1971. Image: Kansas City Public Library.

African American Community

The early decades of the 20th century saw a stream of African Americans migrate to Kansas City from the South. Most took up residence on the city’s east side between 10th and 19th streets. But as neighborhoods became more congested and housing scarce, many began looking to the city’s eastern boundary and settled near the predominately white industrial community of Leeds.

The area was particularly attractive to those wanting to become land owners. Unlike white developers in other areas in the city, those in Leeds were willing to sell to black home buyers. While most residences were small, two-room bungalows — many without electricity, running water and other modern amenities — they were affordable.

A row of homes near 36 Street Terrace and Bellaire Avenue in the Hollie subdivision. Large front porches served as living spaces and bedrooms for many Leeds residents during the heat of the summer. Image: 1940 Tax Assessment Photograph Collection, Kansas City Public Library.

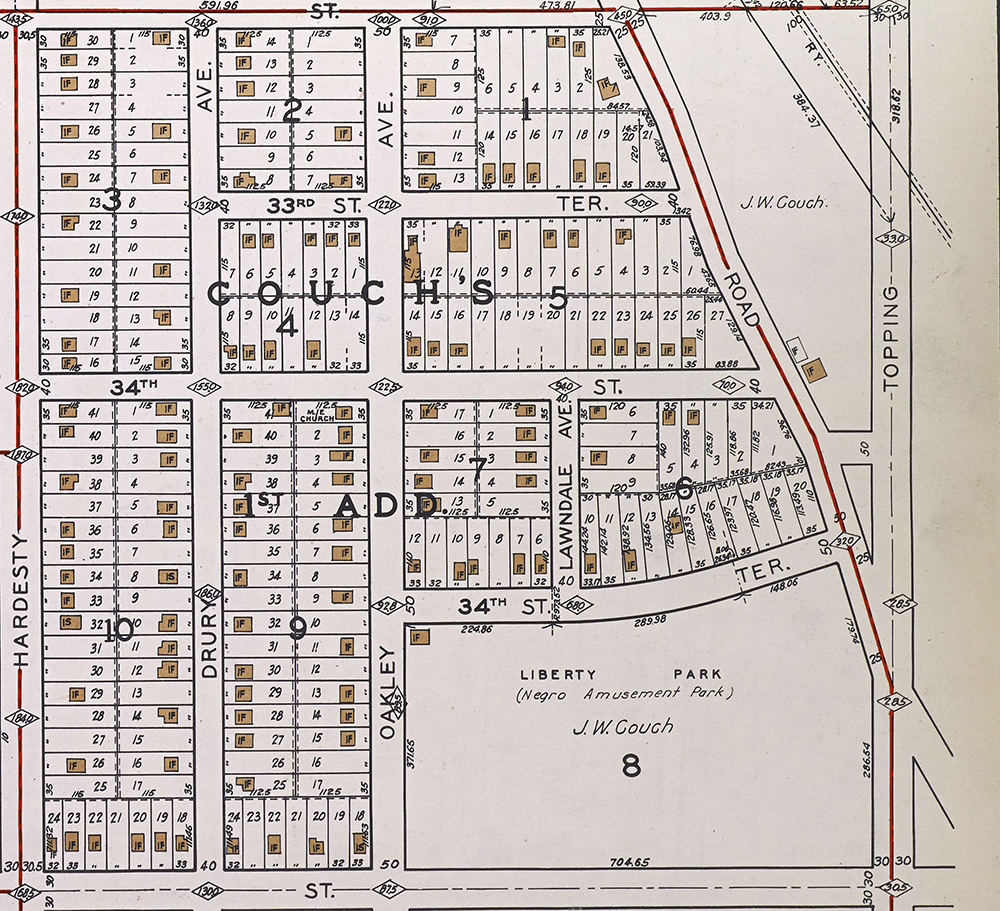

One developer who opened a subdivision to African Americans was J.W. Couch, who joined his wife in filing for Couch’s 1st Addition in 1915. It extended from 33rd to 36th Street and from Hardesty Avenue east to Raytown Road.

The development would later include Liberty Park, a popular gathering spot and recreational area for African Americans. During a time when public parks in Kansas City were segregated, black residents could enjoy swimming, baseball, dances, amusement rides and other attractions that were unavailable to them elsewhere.

Atlas of Kansas City, MO, and Environs, 1925, showing a portion of the Couch’s 1st Addition subdivision. Liberty Park is identified in the lower right corner. Image: FIMo map database, Kansas City Public Library.

In subsequent years, the neighboring Hollie, Dunbar Heights and Way’s Addition subdivisions also were settled by African Americans. Although separated from the Leeds Industrial District by the Blue River, residents began referring to the new communities collectively as Leeds.

Despite being within the boundaries of Kansas City, it was a rural community. This appealed to African Americans on the city’s congested east side, especially those who had migrated from small country towns in southern states. Leeds offered a return to a more pastoral lifestyle with open spaces to grow food and raise animals, as well as hunt and fish.

It was also a good place to raise a family. In a 2003 Kansas City Call article about Leeds, historian Joe Louis Mattox interviewed several former residents who described it as a “safe haven with cheerful kids who played up and down every block and respected their elders.” The neighborhood was abundant with vegetable gardens, fruits trees, and flowered fields, "just like the Garden of Eden."

Leeds residence at 36th Street Terrace and Topping Avenue. Many families in Leeds grew their own food in gardens like the one in back. Image: 1940 Tax Assessment Photograph Collection, Kansas City Public Library.

A school for African Americans was needed as more families with children moved to the area. The Dunbar School, named for black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, opened in 1917 in a small church at 33rd and Oakley Avenue. Student enrollment nearly tripled in three years, from 39 to 96, and a larger eight-room school was constructed near 36th Street and Oakley Avenue.

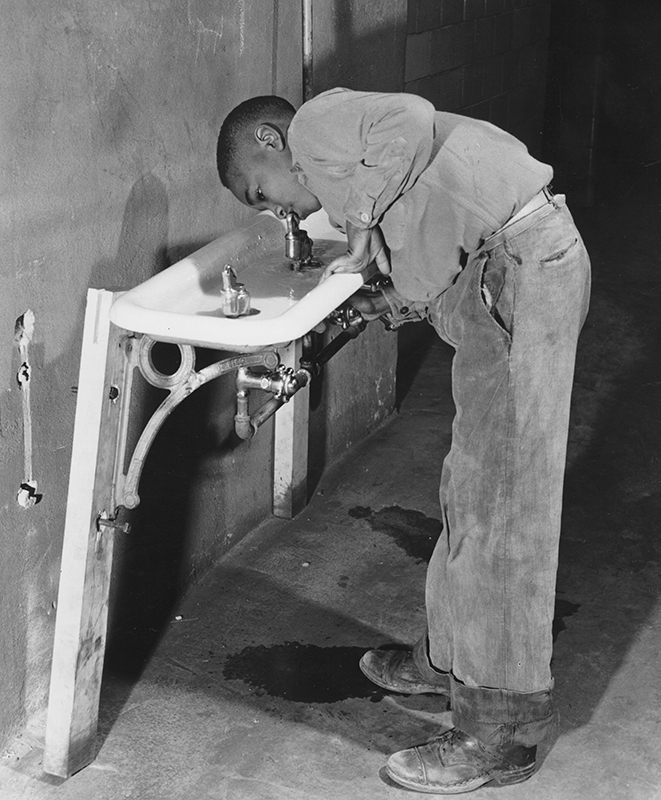

Lacking a high school, older students in Leeds would to travel to Lincoln High School. They not only dealt with the hardship of a daily commute but also ridicule from inner-city youth who looked down on their “country cousins” – many in worn clothes and shoes.

Dunbar School student. Image: KCMO School District Records, Kansas City Public Library

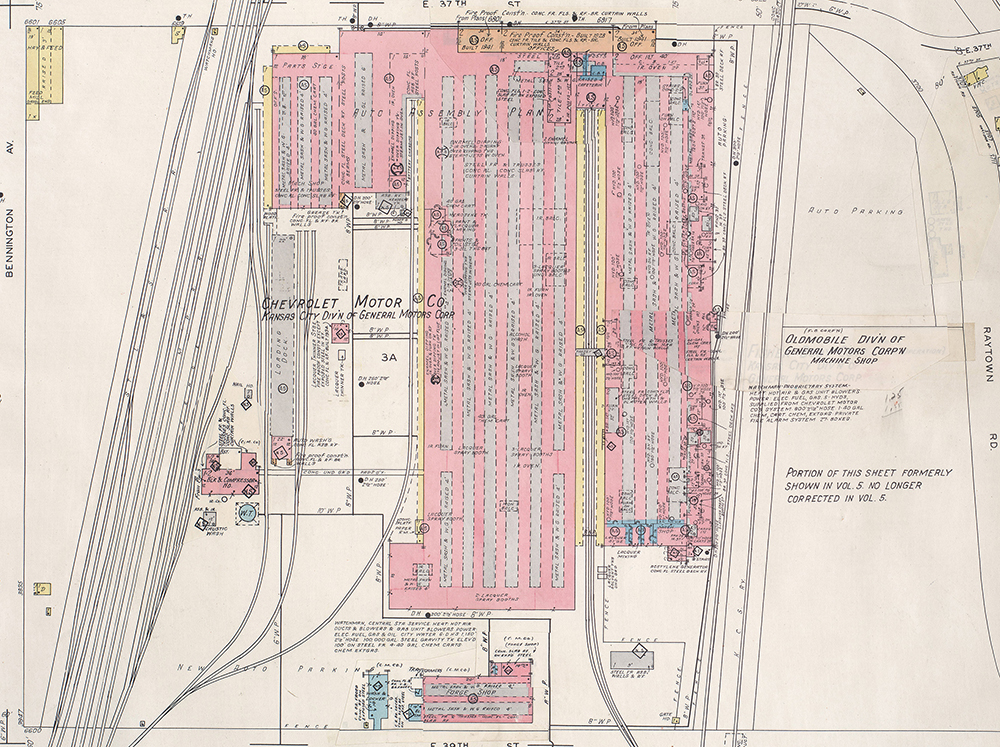

Jobs in Leeds weren’t readily available to its black residents, so most worked construction and other labor jobs near downtown Kansas City or in packing houses in the West Bottoms. But the 1928 opening of General Motors’ Chevrolet Motor Co. and Fisher Body assembly plants at East 37th Street and Bennington Avenue offered employment closer to home. At their height of production, the two plants had more than 5,500 workers.

1945 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map showing the Chevrolet Motor Company assembly plant on East 37th Street, between Bennington Avenue and Raytown Road (currently the site of the Leeds Industrial Park). The plant closed in 1988. Image: Kansas City Public Library.

Leeds saw a period of prosperity following World War II with more residents finding work in nearby manufacturing plants. Accordingly, more homes in the black neighborhoods had indoor plumbing and running water.

However, this prosperity also led to more families leaving the neighborhood. By the 1950s, with other sections of the Kansas City becoming less segregated, many Leeds residents sought better housing in neighborhoods that were formerly restricted to whites. As vacancies increased, the area gradually fell into decline and many of the original buildings were razed over time.

The community of Leeds left a lasting impression on those who lived there. Family, love, and self-reliance were common themes in stories shared as part of an exhibition, “Leeds: A Historic Black Community in Kansas City, Missouri,” at the Bruce R. Watkins Heritage Center in 2003.

Additional information and anecdotes about life in Leeds are found in historian Gary Kremer’s essay, "'Just Like the Garden of Eden': African American Life in Kansas City’s Leeds," published in the Missouri Historical Review and in his book Race & Meaning: The African American Experience in Missouri.