KC Black History: The end of Kansas City’s segregated hospital system

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Michael Wells | lhistory@kclibrary.org

A reader recalling her mother’s experience as a nurse during the integration of Kansas City’s hospital system in the 1950s, asked “What’s Your KCQ?” — a partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star — to investigate how equal treatment and desegregation came to the city’s Black hospital.

For decades prior to the 1950s, General Hospital No. 2 was one of the only medical care options open to Black Kansas Citians. When the city built its first municipal hospital in the 1870s, it reserved only a few beds for Black and other minority patients. The 1903 flood made evident the need for additional hospital capacity. Victims overwhelmed available beds and Convention Hall had to be outfitted as a temporary hospital.

In the disaster’s aftermath, the city’s Black doctors lobbied for a hospital that could not only adequately care for patients, but that could serve as a training ground for Black medical professionals.

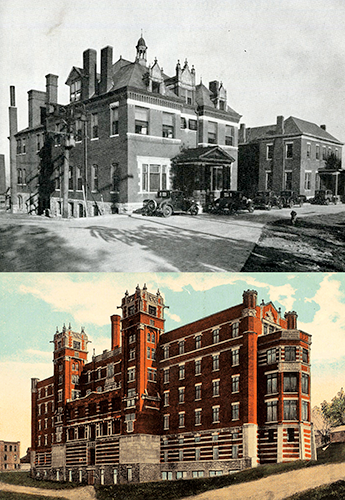

Their advocacy paid off. The city opened a new hospital in 1908 and redesignated the old building at 22nd and Locust streets as a Black hospital. Thus, General Hospitals No. 1 and No. 2 were born.

and the 1908 General Hospital No. 1 (bottom). | Black Archives of Mid-America

Unfortunately, conditions at No. 2 were less than ideal. In what would become a running theme, staff suffered from supply shortages of every kind and had to make do with hand-me-down equipment. The need for a new facility quickly became apparent.

Not until after No. 2 sustained heavy damage in a 1927 fire did the city approve a plan for a purpose-built Black hospital. Some chalked the speedy approval up to the Black community’s years’ long support of Boss Tom Pendergast. Many were grateful for the new hospital, but they would soon learn that the gesture carried a cost.

When the city chose a site along the city’s unofficial north-south color line — Michigan Avenue just north of 27th Street — white residents decried the decision. The Linwood Improvement Association forced the city to reconsider, caving into white residents who said they feared a drop in property values if people of color strayed too far south.

The city chose a new spot at 22nd Street and Kenwood Avenue just north of General Hospital No. 1.

When the new building opened in February 1930, The Call called it “the most modern public hospital in the country,” and boasted of its eight floors filled with “brand new, spic and span” equipment.

Yet, problems lurked beneath the new veneer. Overcrowding was almost immediately a concern. A 1931 report by the chamber of commerce stated that General Hospital No. 2 was already housing 179 beds in a building designed to hold 110. The segregated staffs were instructed to keep interaction to a minimum, and if travel between the facilities was necessary, it was to be done using a tunnel that passed beneath 22nd and 23rd streets.

The hospital also never became the teaching institution many had hoped for. Doctors could fulfill their post-graduate residencies there, but it offered no specialty training programs. Consequently, Black patients in need of specialized care had to wait for white doctors to make time to see them.

Staffing was also an issue. The Pendergast Machine’s total control over municipal affairs meant that political favor often determined who received jobs rather than applicants’ qualifications. Superintendents at No. 2 often came and went following elections.

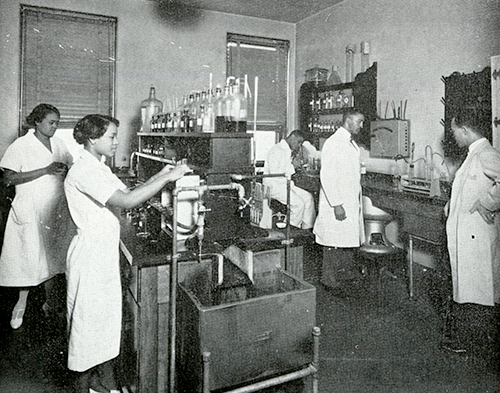

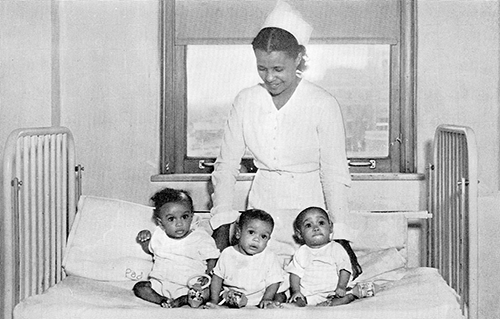

Despite its shortcomings, Black doctors regarded General Hospital No. 2 as one of the premier destinations in the nation to receive post-graduate training. And with its nursing school, Kansas City helped staff Black hospitals across the country.

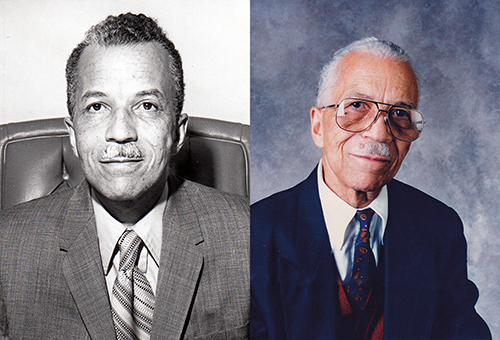

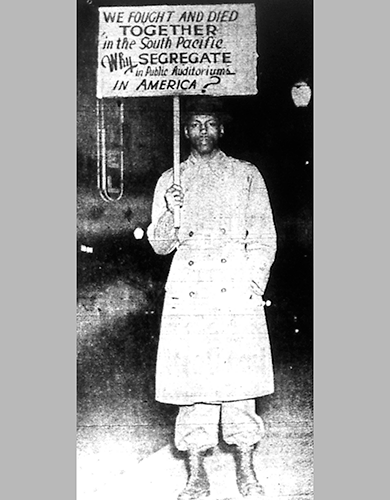

But, change was in the air. During World War II, Black citizens served in the Army medical and nurse corps and experienced the efficiency of well-staffed and adequately supplied hospitals. After the war, conditions back home frustrated them. War veteran and doctor Samuel U. Rodgers added his voice to a group of Black physicians demanding change from the city. Initially, their pleas went unanswered.

in February 1947. Jeffries was one of many Black World War II veterans who were dissatisfied

with segregation in publicly funded venues and organizations after returning home. | The Call

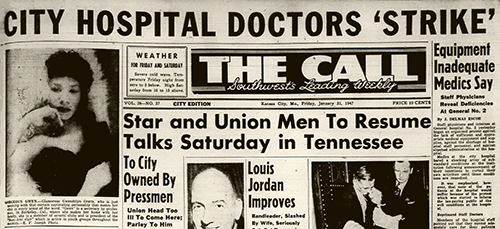

Finally, on January 30, 1947, Rodgers and other Black doctors went on strike. They promised to take care of everyone in the hospital but refused new admissions. The Call reported that the doctors were tired of overwork and providing quality care through sheer determination. They were tired of unqualified staff, tired of not receiving specialty training, and tired of doing without appropriate supplies.

Administrators cited nationwide shortages for lack of supplies, but the striking doctors were confident someone was diverting their orders to the white hospital.

It only took a few days for the city to agree to the strikers’ demands. Conditions improved, and within a few months, General Hospital No. 2 was on track to become an American Medical Association approved teaching hospital.

The strike didn’t remedy all that plagued Kansas City’s Black hospital though. In 1951, a visiting white doctor told The Call that “Life is cheap at General No. 2, and a patient’s comfort doesn’t mean much,” citing unsanitary conditions, poor staff attitude, and rampant inefficiency.

It was exactly the inefficiency and waste from the operation of two hospitals with nearly identical staffs and services that put them on a path to integration.

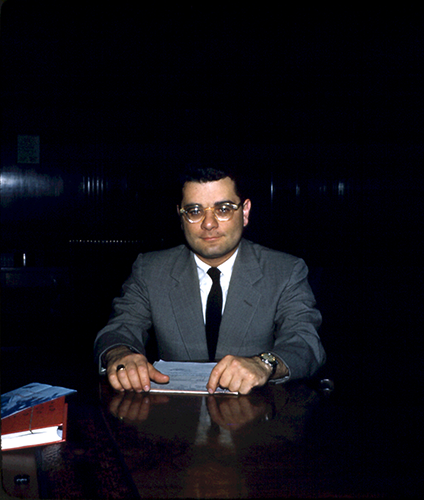

In 1954, the city’s budget department hired Al Mauro. As a research analyst, he looked for ways to trim fat from city expenses, and the segregated hospital system was a gigantic red flag.

Like the Black medical professionals who served during World War II, Mauro was impressed by his military experience. He was in the Army in 1948 when President Harry Truman ordered the immediate integration of the armed forces. Mauro witnessed units desegregate over the course of a single day. He’d been struck by how quickly his fellow Black and white soldiers became accustomed to living and working together.

So, he thought it best to rip off the bandage quickly when it came to the city’s segregated hospitals. The plan was announced in 1956.

Unable to ignore the cost savings, the city council supported consolidation, though administrators at the white hospital weren’t keen on Mauro’s plan to move No. 2 staff and operations into their building.

Concerns were raised over the allocation of available beds and toilets. Mauro noticed their protests indicated a belief that segregation would endure within the consolidated institution. He assured them that the number of beds and toilets would be sufficient for a fully integrated hospital.

During a December 31, 1957, hearing, The Call spoke to City Councilman Thomas J. Gavin who said of the white hospital leaders, “They say they want to integrate, but when they get into back rooms, it’s a different story.” At the same hearing, Mayor H. Roe Bartle declared he was tired of reading reports, tired of double talk, and tired of waiting. Bartle demanded immediate action. Despite ongoing requests for more time, the city council approved the plan.

Some Black hospital employees also felt reluctant to integrate, but for different reasons — they primarily feared losing jobs to their white counterparts after the merger. Mauro, who was tasked with carrying out the consolidation, guaranteed Black hospital staff employment if they chose to stay.

And slowly but surely, change started to happen. The nursing schools were combined, followed by the hospital wards, and in 1958, the city began an expansion of the integrated hospital. And like Mauro had observed when his Army unit integrated, the hospital’s Black and white staff quickly became accustomed to one another. By 1959, the city’s segregated hospital system ceased to exist.

While certain members of the white hospital leadership were apprehensive, both staffs had enough good-will and commitment to care that integration succeeded.

Figures like Samuel U. Rodgers, who experienced more equitable treatment of Black medical professionals serving his country overseas than at home, and Al Mauro, who had witnessed the rapid integration of Black and white soldiers, helped lead the way.

Years later, at a reunion for General Hospital No. 2 nursing school alumnae, a retired nurse said of the integration process, “When someone cries out in pain, you don’t look first to see if he is Black or white. As a nurse, you respond … Pain doesn’t carry a color.”

The consolidated hospital became Truman Medical Centers, later renamed University Health. The General Hospital No. 2 building became the Western Missouri Mental Health Center.

Some Kansas Citians never got over the building’s negative associations and viewed it as a symbol of the city’s segregationist past. Others, who associated the building with the autonomy of Kansas City’s Black community or as a place where family members were cared for or received medical training, viewed it as a landmark worthy of preservation. In 2003, many put their mixed emotions to rest when the old No. 2 building was torn down.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.