KC Black History: Do you know the teacher who integrated a school before Brown v. Board?

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Kynala Phillips | Kansas City Star

The old building is white and almost anonymous as you drive by. There’s a giant wooden cross on it.

Before this single-story building was a church, it was a school — where Black teachers taught and Black students learned. It was here where a teacher helped Black parents win a landmark school desegregation case, five years before the United States Supreme Court made its famous ruling on Brown v. Board of Education.

The school was Walker Elementary in Merriam. It was one of the many schools where Black children attended as Jim Crow laws across the United States made segregation legal.

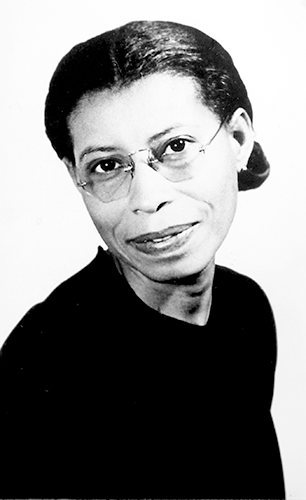

Corinthian Nutter was the school’s only certified teacher. And after parents of students from Walker Elementary decided to boycott the school’s deplorable conditions and sue the school district in hopes of gaining a more dignified place to learn, it was Nutter who subversively taught their children from private homes and stood as a key witness in the case.

“Had not someone like her said, ‘I’m with you. Let’s do this. I’ll hang in there with you and teach the kids to the best of my ability,’ this might not have happened then,” Harvey Webb, one of her students, previously told The Star.

Nutter died Feb. 10, 2004 at her home in Shawnee at age 97.

“Today it’s hard to imagine the courage required for a modest and reluctant revolutionary such as Nutter, battling decades of Jim Crow habits while far removed from the seats and conventions of power,” LynNell Hancock, an assistant professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, wrote in The Washington Post on March 10, 2004. “It was such a lonely fight, in fact, that she remained largely unrecognized.”

From Texas to Kansas City

Born in Forney, Texas, on Dec. 10, 1906, Nutter’s paternal grandfather had been enslaved. Her father worked on the railroads. Her mother picked cotton.

Growing up, Nutter rarely went to school. Instead, she tagged along with her mother to the cotton fields. But Nutter didn’t pick it. She was allergic.

Her parents didn’t receive formal education. They were illiterate.

At 14, Nutter dropped out of school, got married to her first husband and worked at a beauty shop. But after a couple years, her mother died, and she got divorced. She didn’t see much of a reason to stay in Texas.

A friend told her that in Kansas City, women lifted their dresses as they danced. Nutter wanted to see that. So she headed north.

When she moved to the area, the YWCA helped her find an apartment with a local Black family, The Star reported on Feb. 3, 2002.

Soon, she went back to school. Her commute to earn a high school diploma was arduous: A bus in Kansas City took her to Kansas City, Kansas, where she would get off at the final stop on Quindaro Boulevard, The Call, a Kansas City newspaper serving Black Kansas Citians, reported on Oct. 17, 2003. She then walked another mile to arrive at Western University, the only Historically Black College in Kansas that operated from 1865-1943.

She graduated from Western in 1936, completed the school’s junior college program with a Kansas teaching certificate in 1938 and ended up getting a bachelor’s degree in education from Emporia University in the 1950s.

In 1943, she was hired as the only certified teacher at a two-room school in Merriam.

The school’s name was Walker Elementary.

in private homes while waiting for a court ruling on segregated schools.

‘Schools shouldn’t be for a color’

The conditions of Walker Elementary weren’t just unequal to those of the local schools for white children. They were repulsive.

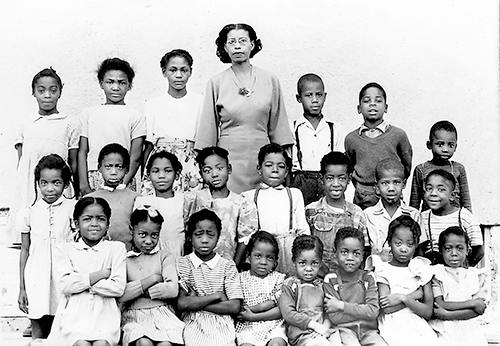

More than three dozen Black children crammed into one classroom — later two — where teachers taught eight different grades. The school lacked a cafeteria, an auditorium, reliable heating, up-to-date textbooks and indoor plumbing. Children went to the restroom in an outhouse next to a bunch of scrap metal. That was the playground.

In 1947, School District 90 opened a new school right by Walker Elementary. The school was called South Park Elementary. The school had what Walker did not, including multiple teachers and separate classrooms. It was built thanks to the public proceeds of a $90,000 bond election.

But the new South Park only allowed white students to attend.

Black parents were outraged. Their tax dollars had helped pay for South Park Elementary, but their children weren’t able to benefit from it. The school district trustees justified the segregation by arguing that the school’s enrollment was based on the attendance areas drawn up for each school.

In what became known as the Walker School walkout, the Black parents removed 39 of their 41 children from Walker Elementary.

Instead of continuing to teach at Walker, Nutter, “left her job there and helped teach the students for a year in two private homes,” The Star wrote on Nov. 6, 1994.

Parents paid her when they could before the NAACP started compensating Nutter and another teacher, Hazel McCray-Weddington, $50 a month.

A white Russian-Jewish woman who lived right by the new South Park Elementary named Esther Brown was incensed by how the Black students were treated in comparison to white students.

She recommended to Walker Elementary’s parents that they file a lawsuit.

They did.

The watershed desegregation case of Webb vs. School District 90 went all the way to the Kansas Supreme Court, with Nutter serving as a key witness.

“‘I just told them the truth,’” Nutter told The Star in a profile on Feb. 3, 2002. “The school was dilapidated, we had no modern conveniences, had to go outside to go to the toilet. And if they were going to build a new school and the parents were paying taxes like everybody else, why couldn’t their children go? Schools shouldn’t be for a color. They should be for children.”

On June 11, 1949, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled in favor of the parents, writing, in part, that equal facilities must be provided to children. The Court also struck down the school district’s argument that the school’s were segregated because of how the enrollment areas were drawn, writing, ‘(this) allocation must be made, however, upon reasonable basis without any regard at all as to color or race of the pupils within any particular territory.”

South Park Elementary was desegregated beginning with the 1949 school year, and the Black students from Walker could attend the new school alongside white students.

The group helped pay Nutter during the Walker School walkout.

“The victory paved the way for other legal challenges, including the Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education (sic) decision in 1954, which set the course for school desegregation,” The Star wrote on Feb. 3, 2002.

After the South Park integration ruling, Nutter earned a master’s degree in education and fell just short of a doctorate, needing three hours and a dissertation. She ended up accepting a teaching position at Westview Elementary School in Olathe later in her career. She became the school’s principal and retired in 1972.

After retiring, Nutter continued downplaying her role in school desegregation, telling The Star before she died, “I was just the teacher who could tell the tale. I just don’t think I’ve done anything outstanding.”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.