How Was the Non-River State Line That Divides KCK and KCMO Selected? Your KC Q Answered

A recent What’s Your KC Q? submission asked us to explain the odd, seemingly arbitrary state line between Kansas and Missouri as it passes through the West Bottoms. The asker describes himself as a geography nerd with an interest in maps who’s always wondered why the Missouri border doesn’t extend to the Kansas River. When you look at it, the line does seem strange. Just to the north, the state line begins following the more obvious Missouri River. Why not just push the line a few hundred yards west to make things nice and neat? Seems like a no-brainer.

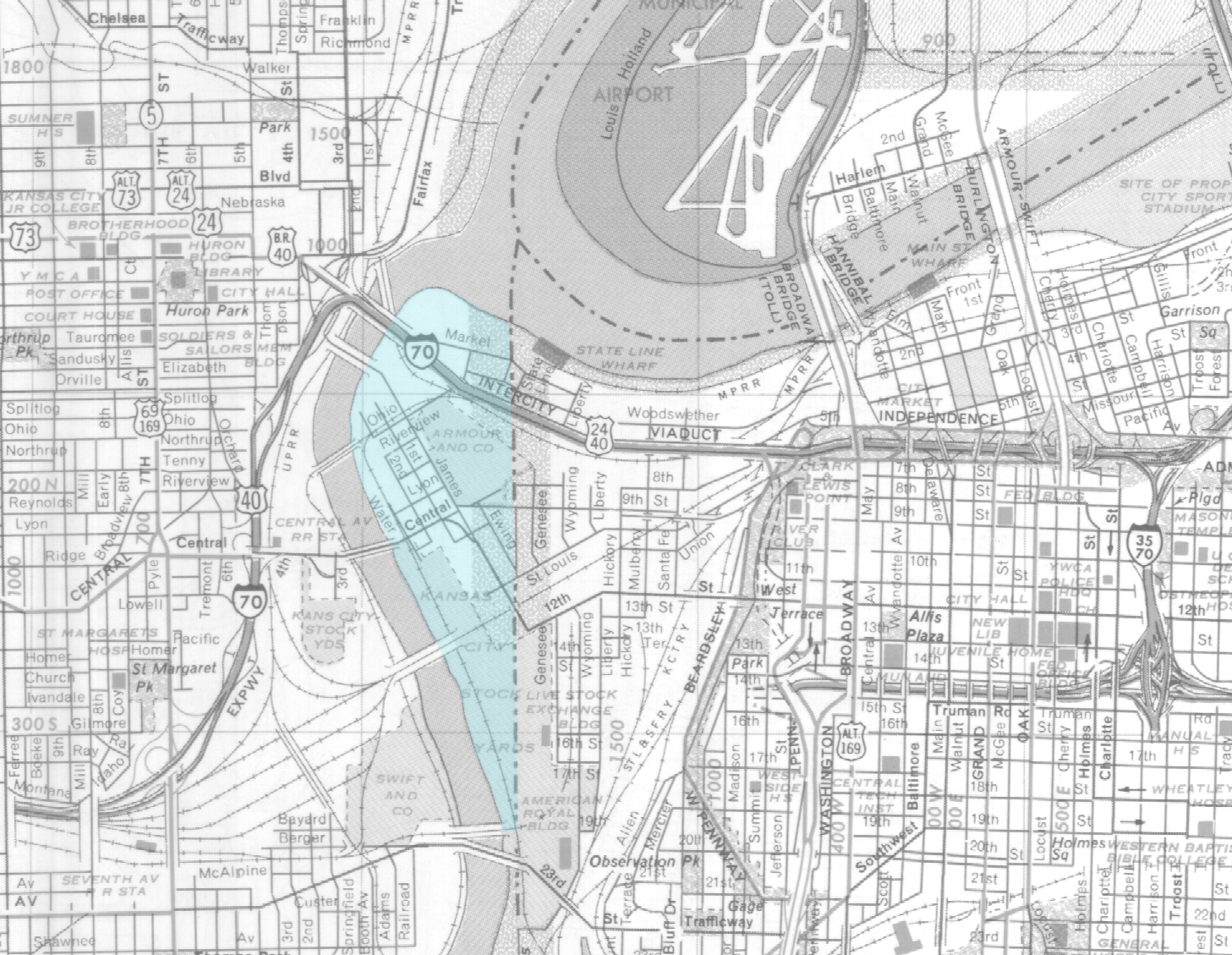

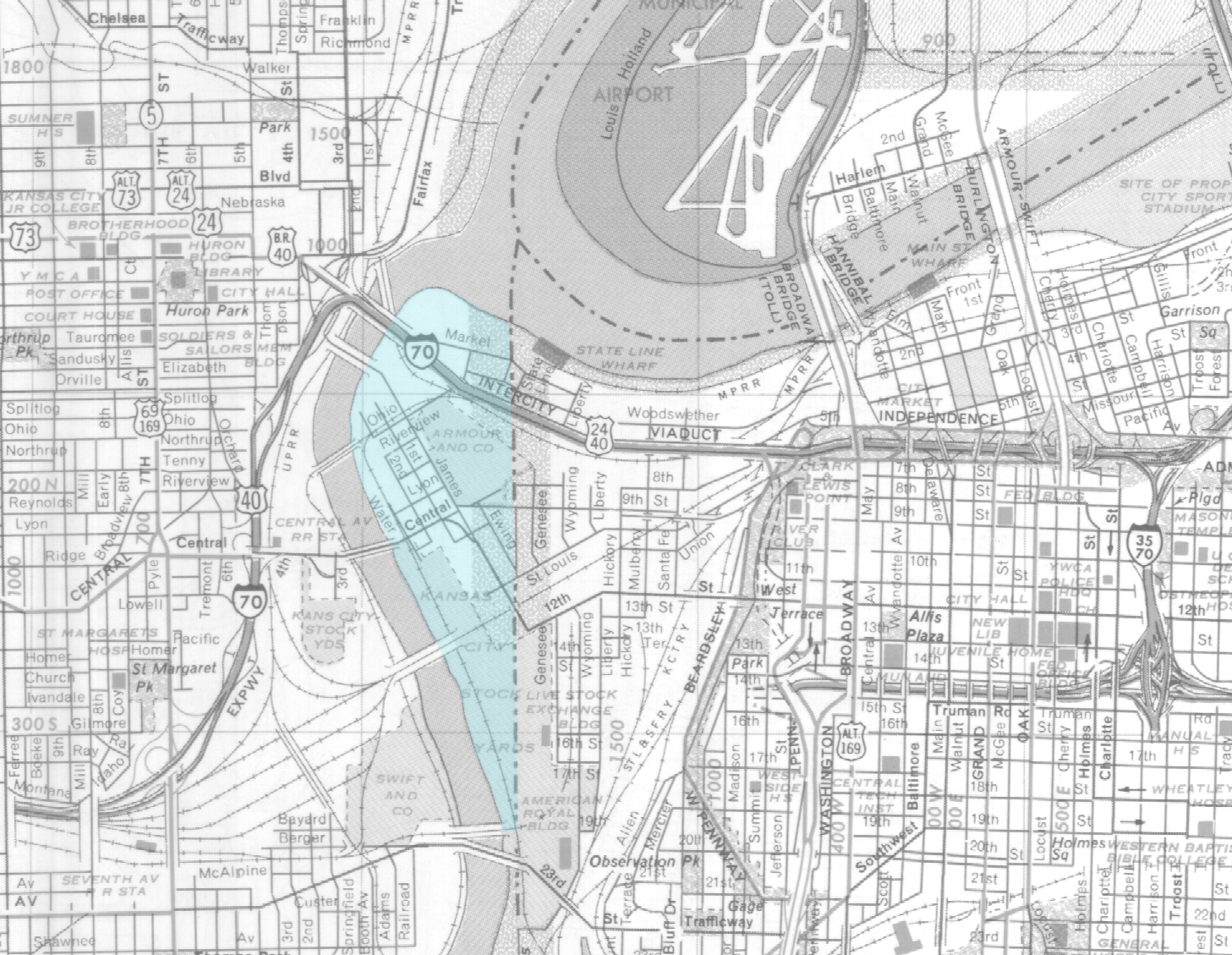

Map of the Kansas City area with the Kansas portion of the West Bottoms highlighted in blue, 1969

Missouri was the first territory within the Louisiana Purchase to be sectioned off for future statehood, but its boundaries were much debated with Native Americans, descendants of the French traders and white settlers all making their claims. Ultimately it would be the various treaties and land sales negotiated between the U.S. and the various Native American tribes already living in the territory that had the most impact on the territory’s western border. First, a treaty signed in 1808 with the Osage Nation ceded a large portion of the future state to the U.S. and established a boundary stretching from Fort Clark (later Fort Osage) south into the future Arkansas Territory. In 1816, surveyor John C. Sullivan – operating with the authority of the U.S. government – was tasked with establishing a line beginning at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers and 100 miles north, then turning east to meet the Des Moines River. And just like that, Missouri had its first western and northern borders.

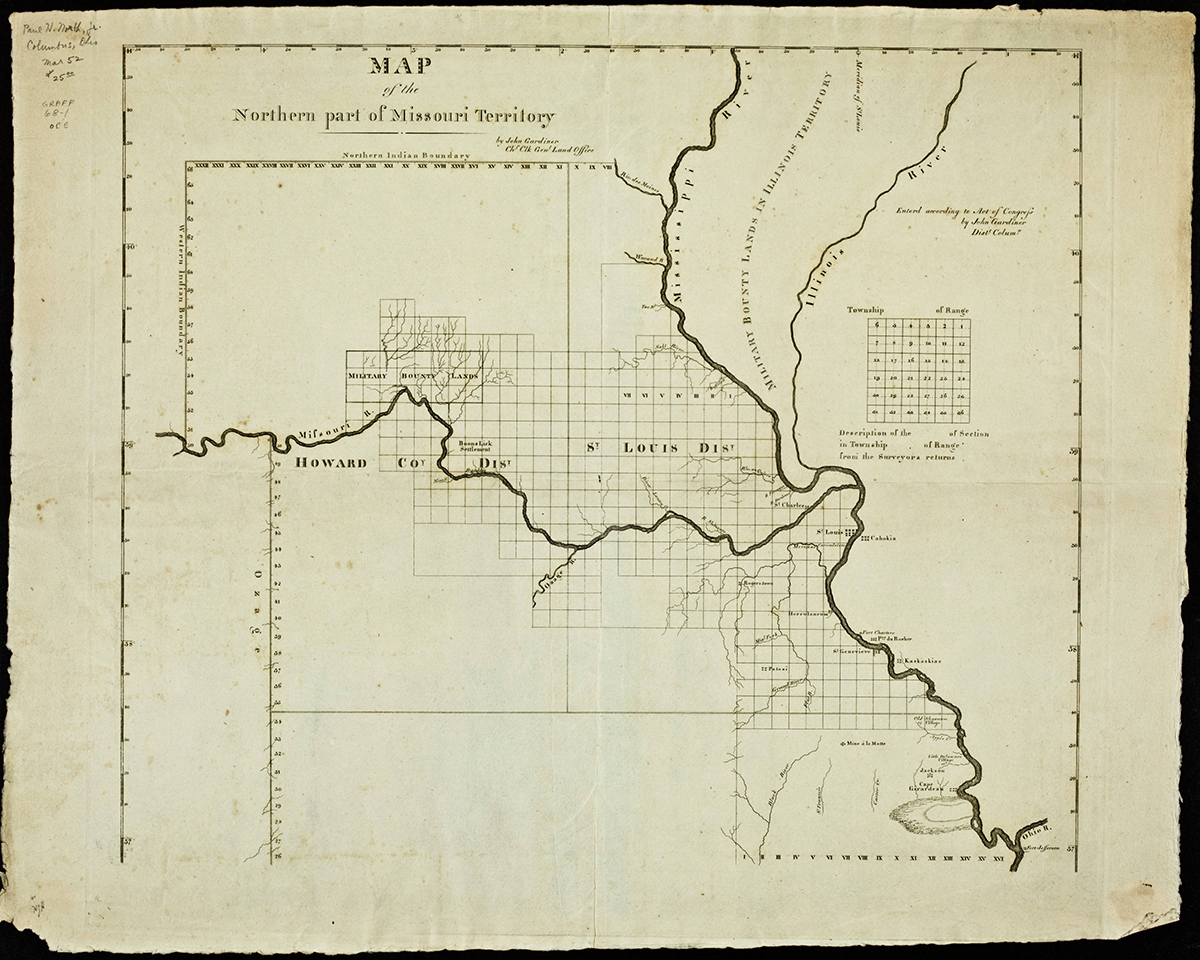

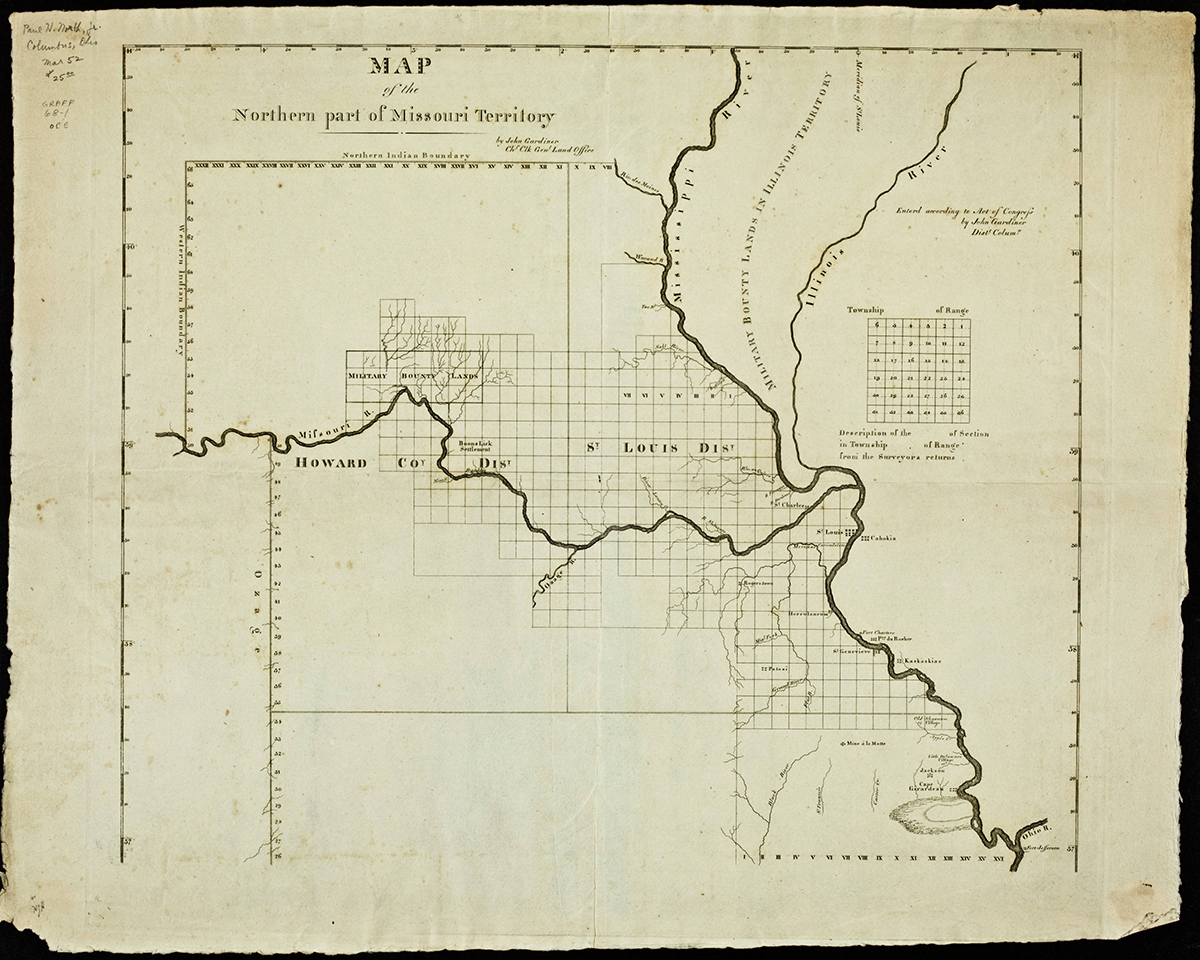

Map showing the first western and northern borders of Missouri. The border with the Osage Nation at that time is shown stretching south from Fort Osage east of modern-day Kansas City. Missouri’s northern border, beginning at the Sullivan Line and stretching east to the Des Moines River, can also be seen, 1817

Despite achieving statehood in 1821, Missouri’s borders remained a little murky. Its western border at that time was described as “a meridian line passing through the middle of the mouth of the Kansas River, where the same empties into the Missouri River.” In 1823, surveyor Joseph C. Brown was dispatched with a team to put those words on the map. In September of that year, Brown’s team set out from the confluence of the two rivers and marked a line consisting of blazed trees and mounds of sod 180 miles south to Arkansas Territory. In 1825, a new treaty with the Osage ceded the remainder of their land in western Missouri and additional lands in modern-day Kansas and Oklahoma to the U.S. Ratification of the Indian Removal Act in 1830 displaced many Native American nations west of this line.

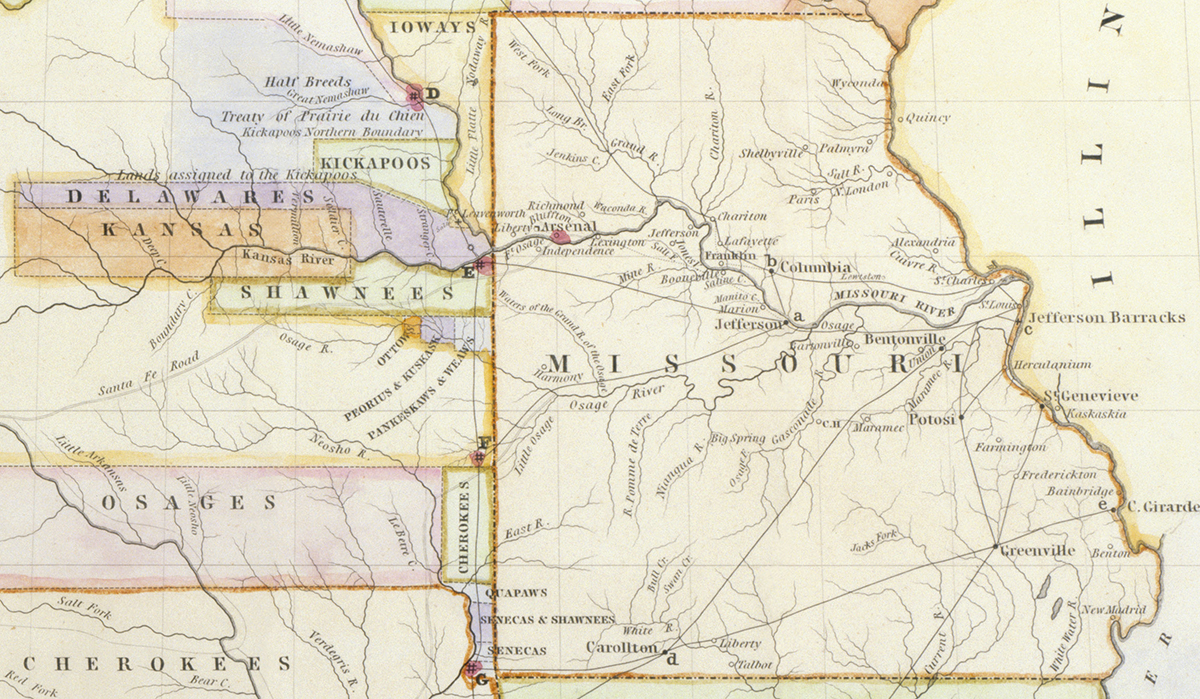

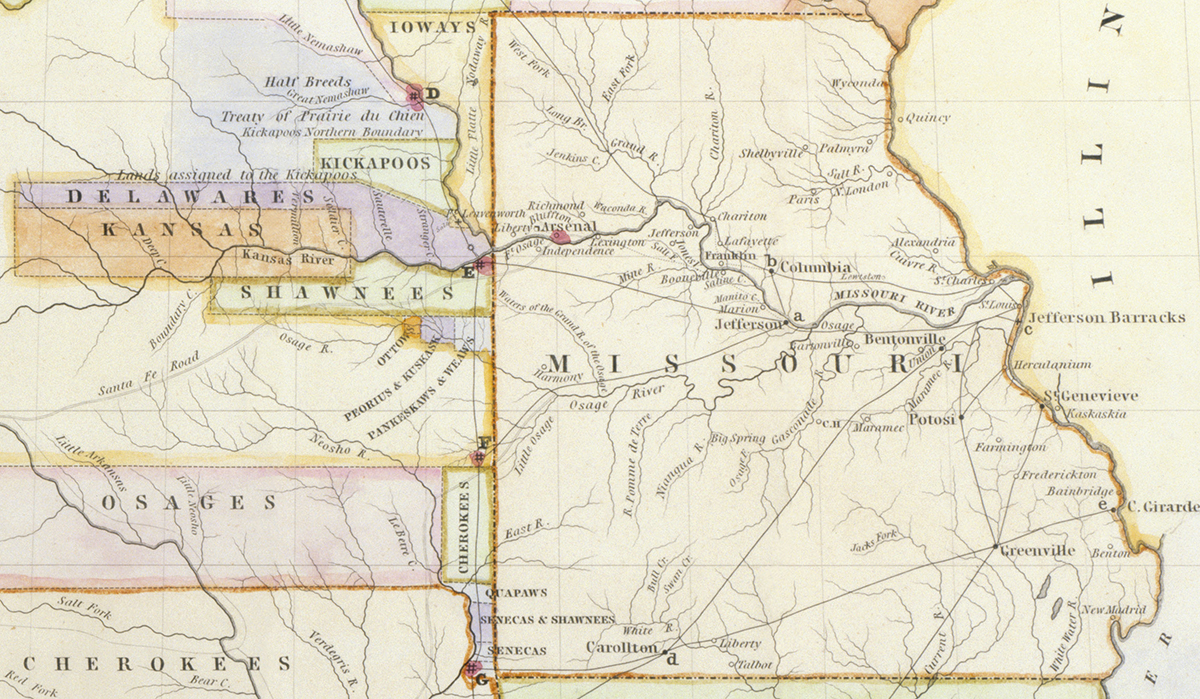

Map showing Missouri’s western borders and tribal reservations set aside after the Indian Removal Act, 1836

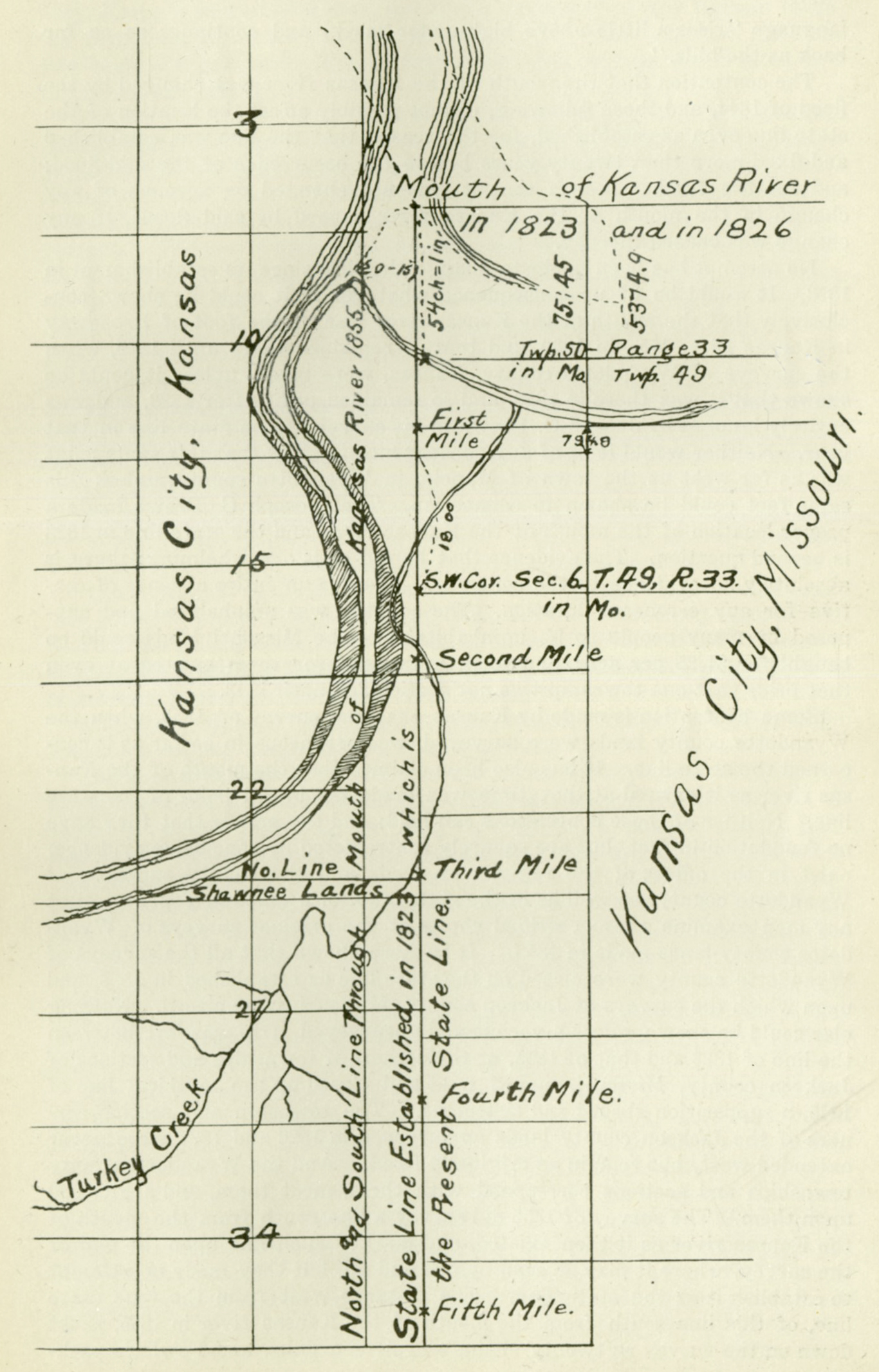

This line held over the years despite an effort to extend the border east to the foot of Broadway and south along the West Bluffs in 1884. The feeling among its advocates being that the Kansas River would have historically run its course anywhere between the bluffs on either of its banks, including the whole of the West Bottoms. Wyandotte County Clerk William E. Connelley conducted an in-depth investigation of the Kaw’s path after 1823 and found no evidence that the river had drastically changed its course since Brown marked off Missouri’s western border.

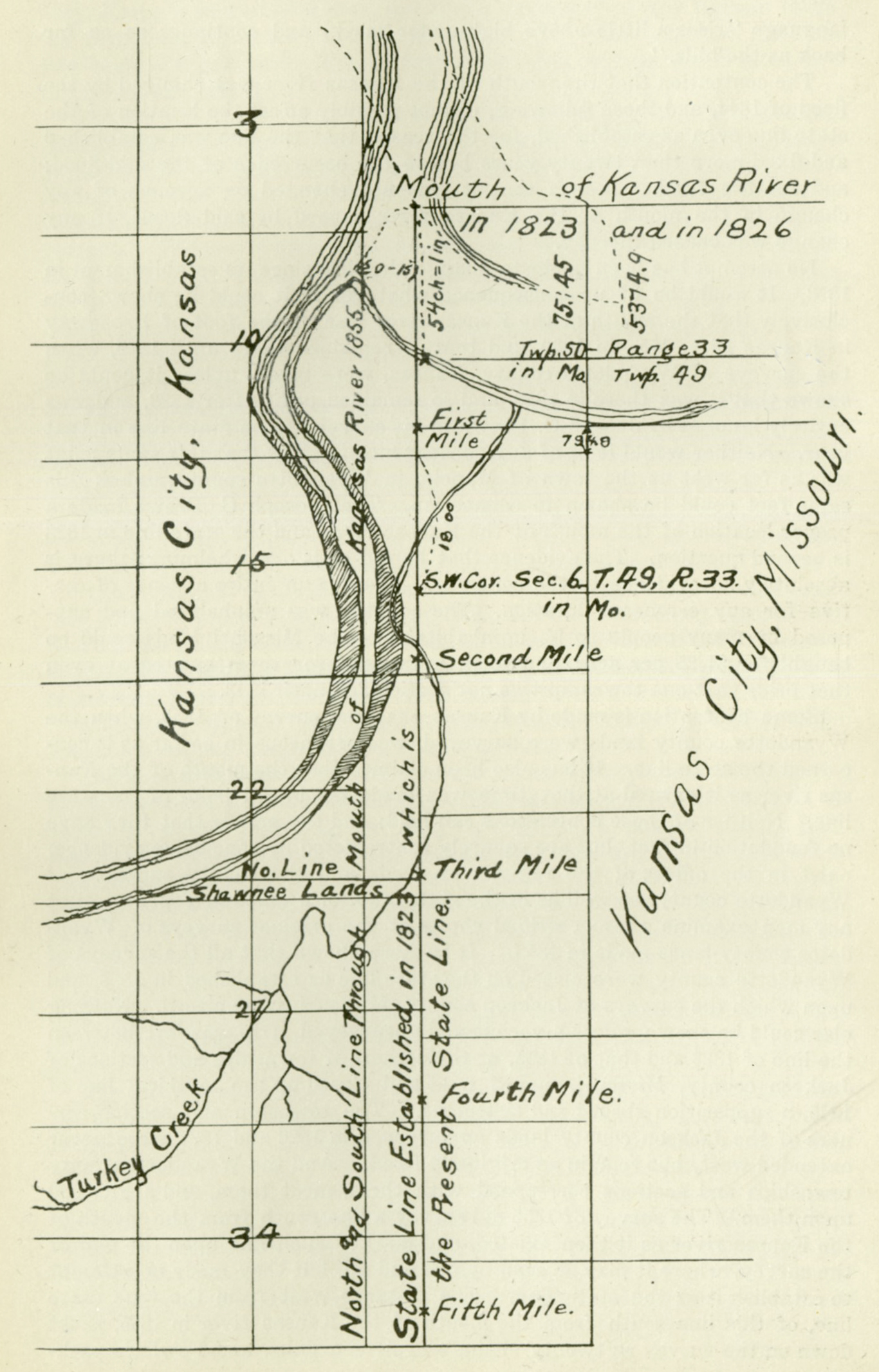

Map drawn by William E. Connelley to illustrate the differences between Brown’s 1823 meridian line where it would have been placed based upon the location of the Kaw during the 1855 survey of the Kansas-Nebraska Territory, 1884

The Missouri River boundary north of Kansas City we know today had yet to take shape at the time of the Indian Removal Act. That would change when the Ioway and Sac and Fox tribes inhabiting the northwest corner of the state agreed to sell their territory west of the Sullivan Line and relocate to reservations west of the Missouri River. The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty, and Missouri formally took control of the Platte Purchase in 1837.

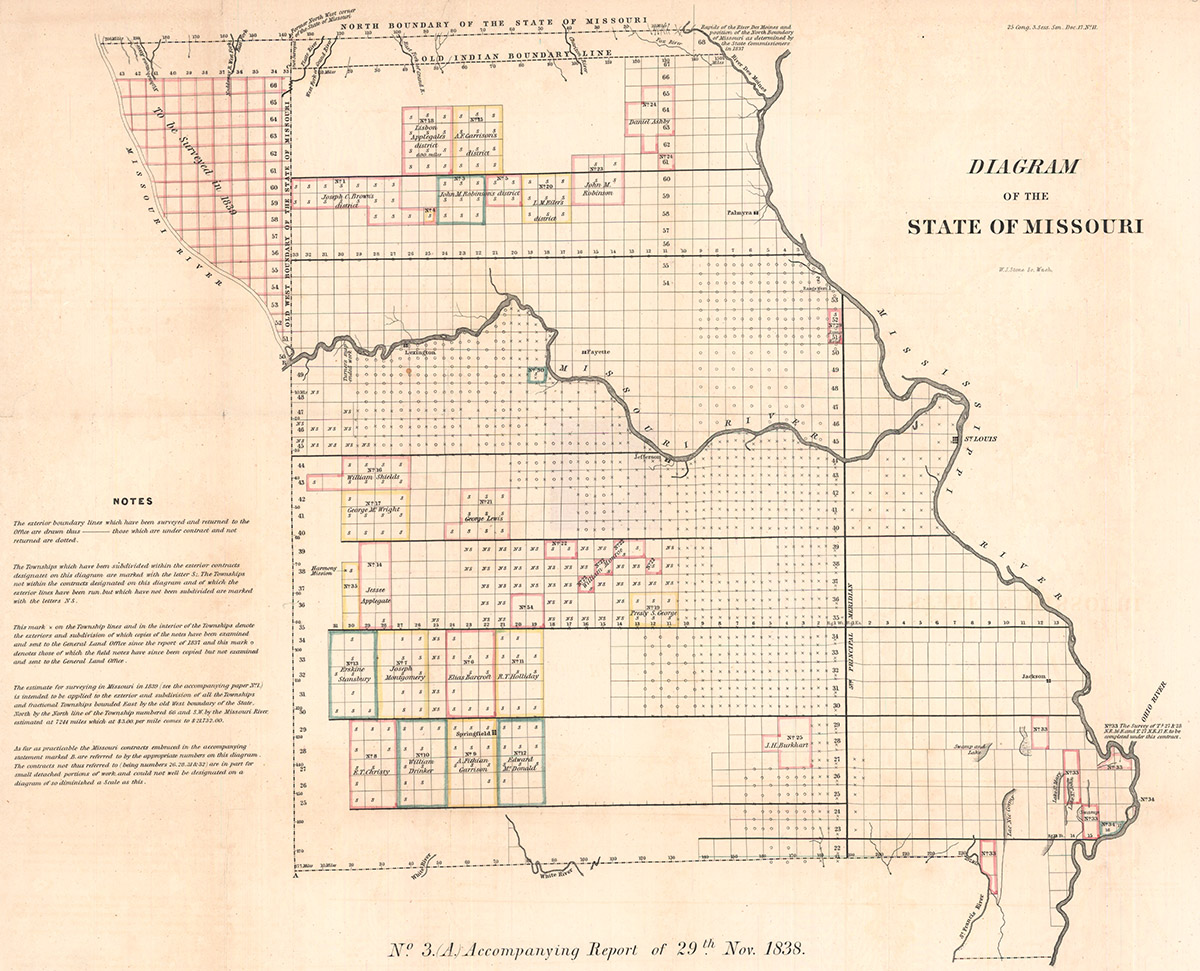

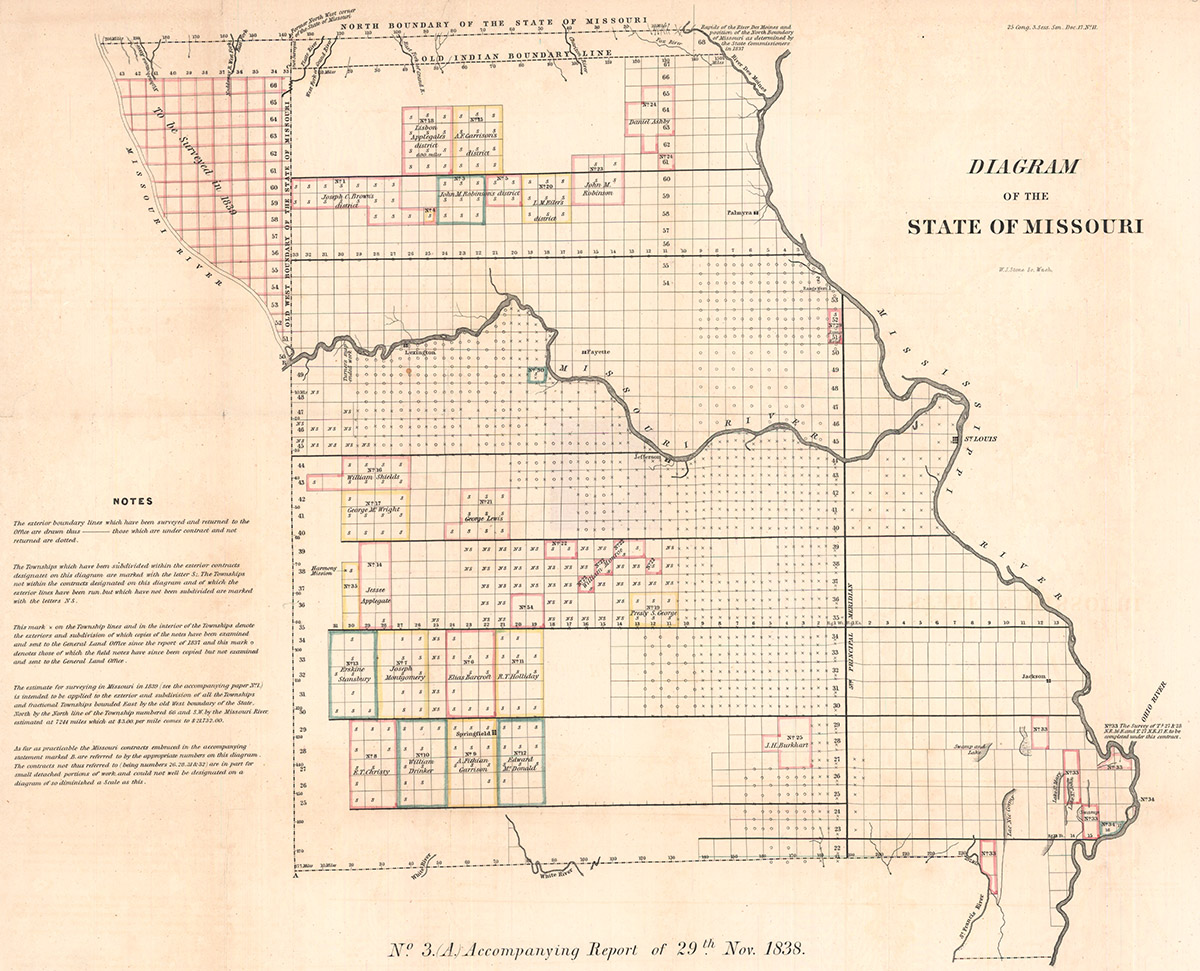

Map showing the Platte Purchase in northwest Missouri, 1838

So, it was the combined forces of Indian removal and white settlement of Missouri that gave us our rather odd West Bottoms state line. We could stop here, but another story emerged in researching this question – one involving Silas Armstrong and the coming of the Wyandot Nation to Kansas. In 1842, the Wyandots signed a treaty with the U.S. ceding their lands in Ohio and Michigan, and in return were promised territory west of the Mississippi River. The original tract set aside for them along the Neosho River was not to their liking, their leaders preferring to settle near the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers. Along with George I. Clark, another prominent Wyandot, Silas Armstrong traveled to Westport to prepare for the arrival of their people. They tried to purchase land from the Shawnees south of the Kansas River but were unable to reach a deal. With their options limited, Armstrong took notice of a narrow strip of government land west of the state line in today’s West Bottoms.

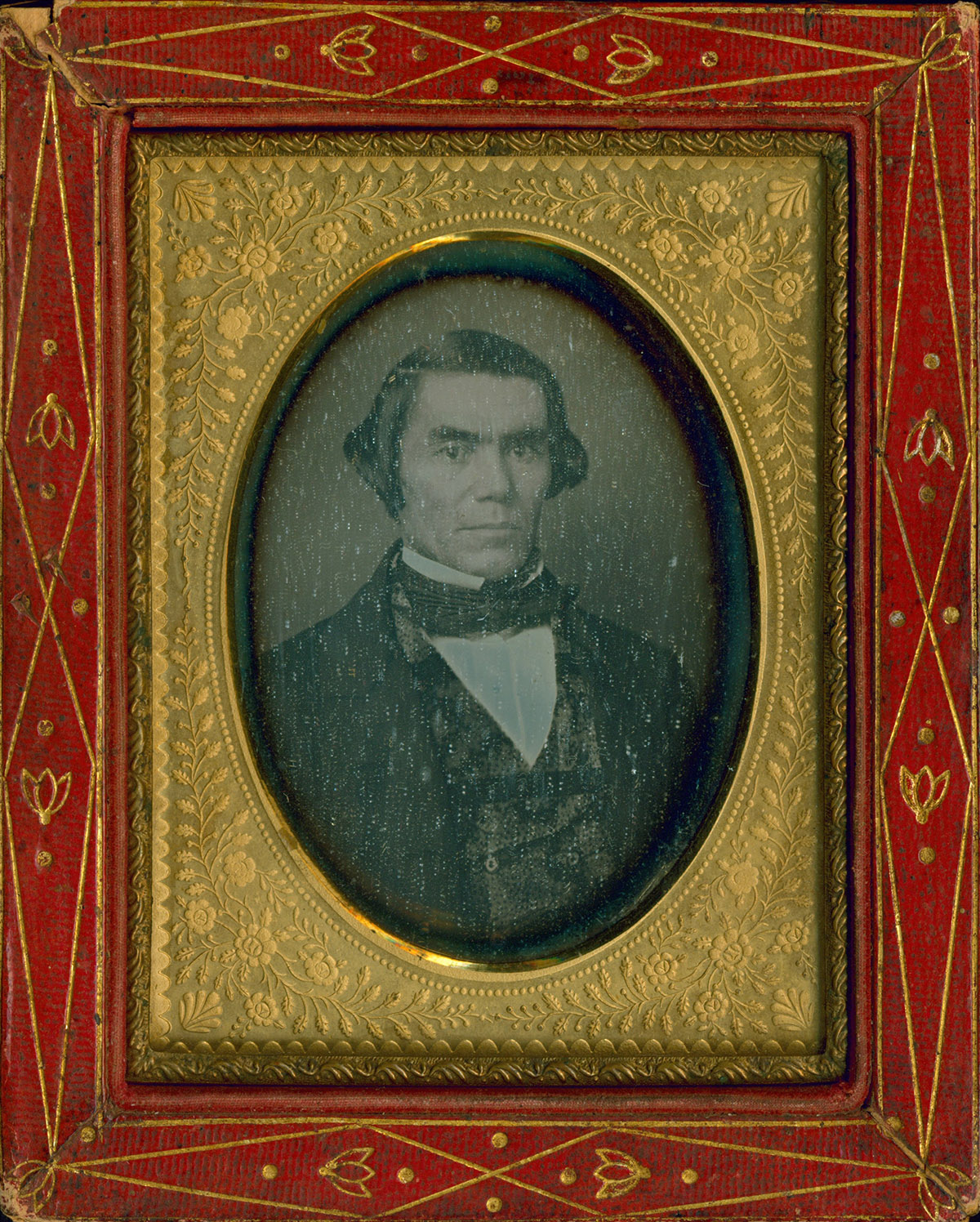

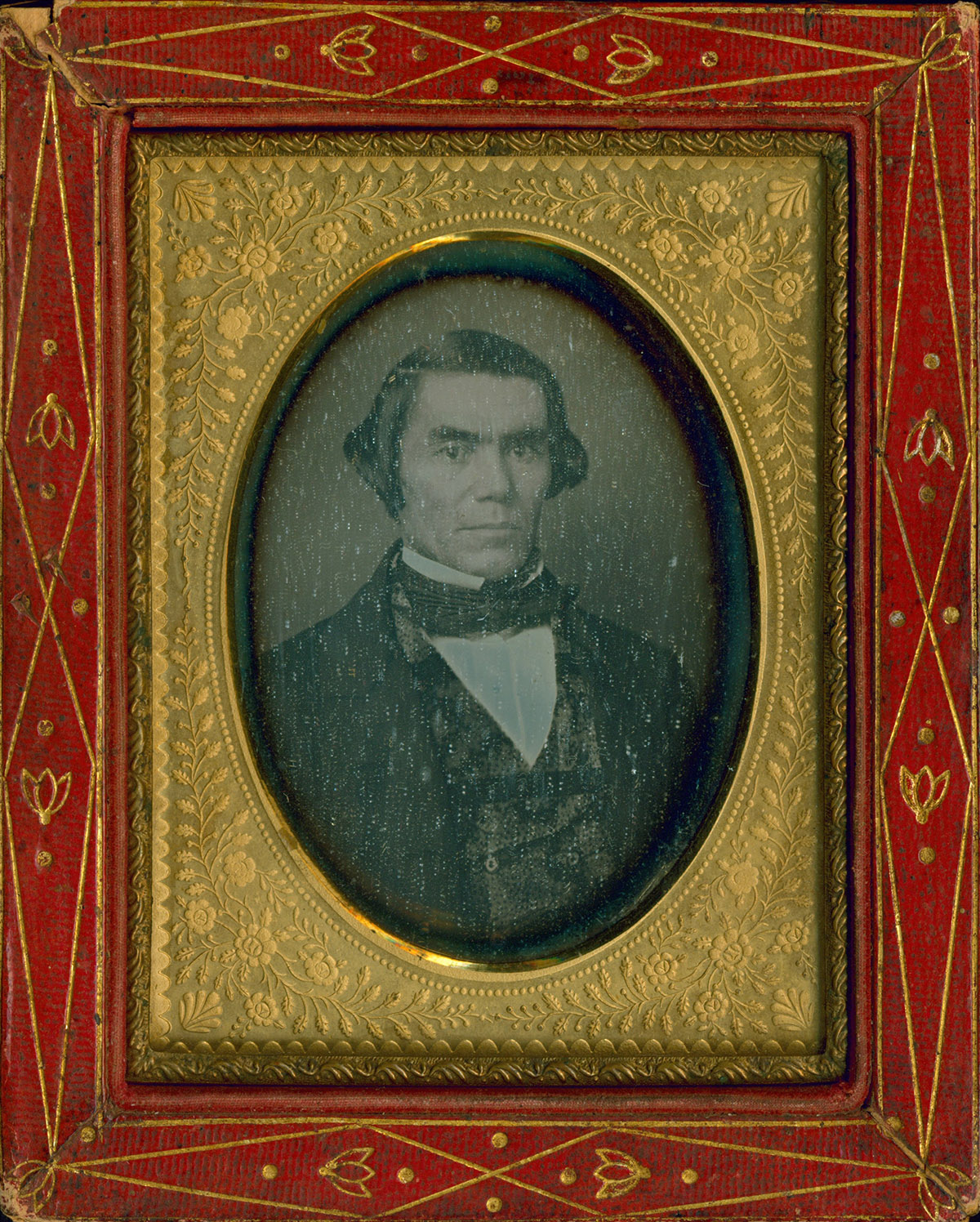

Daguerreotype portrait of Silas Armstrong, n.d., image courtesy of Kansas Room Special Collections, Kansas City Kansas, Public Library

To sweeten the 1842 treaty, the U.S. had promised “to grant by patent in fee simple to each of the following named persons, and their heirs all of whom are Wyandots by blood or adoption, one section of land of six hundred and forty acres each, out of any lands west of the Missouri River set apart for Indian use, not already occupied by any person.” Since this promise was not connected to any specific piece of land, it was thought of as a “floating grant.” Together, the parcels claimed by those listed in the treaty became known as the Wyandot Floats. Armstrong happened to be among the listed names, and viewed the land around the confluence of the two rivers as an ideal location for his float. The arriving Wyandots now had a place to establish a temporary camp while Armstrong and his associates began negotiating the purchase of a new piece of land – this time located just north of the Kansas River on the Delaware Reservation. The sale was finalized in 1843. The Wyandots had found their new home.

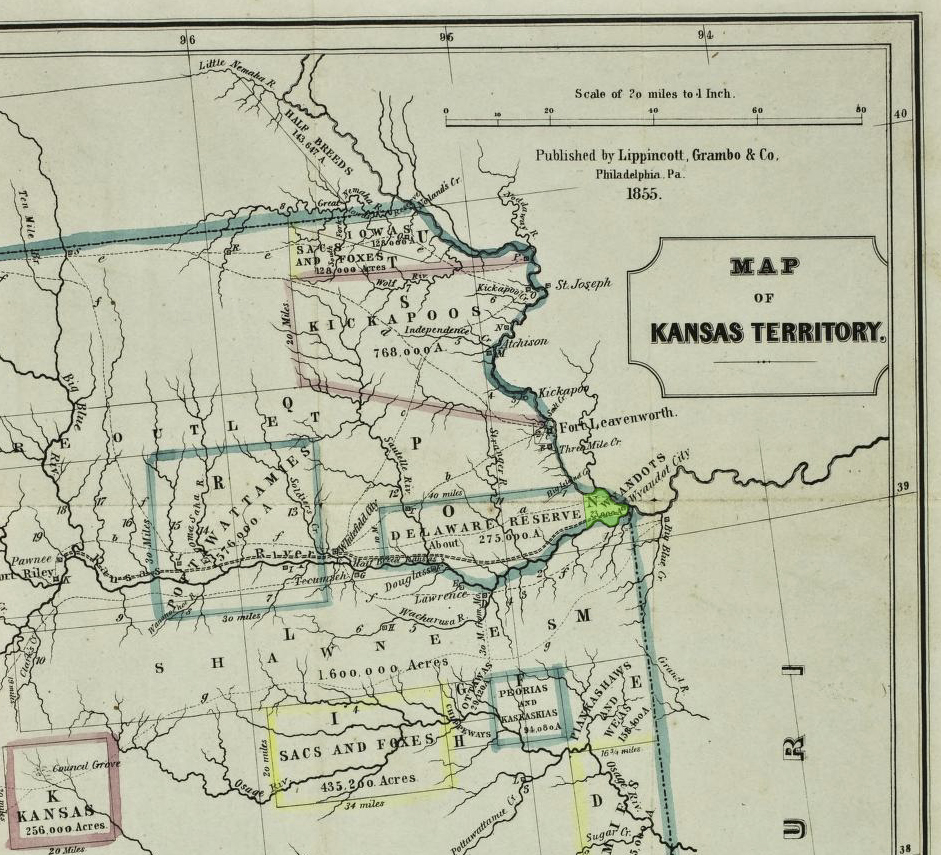

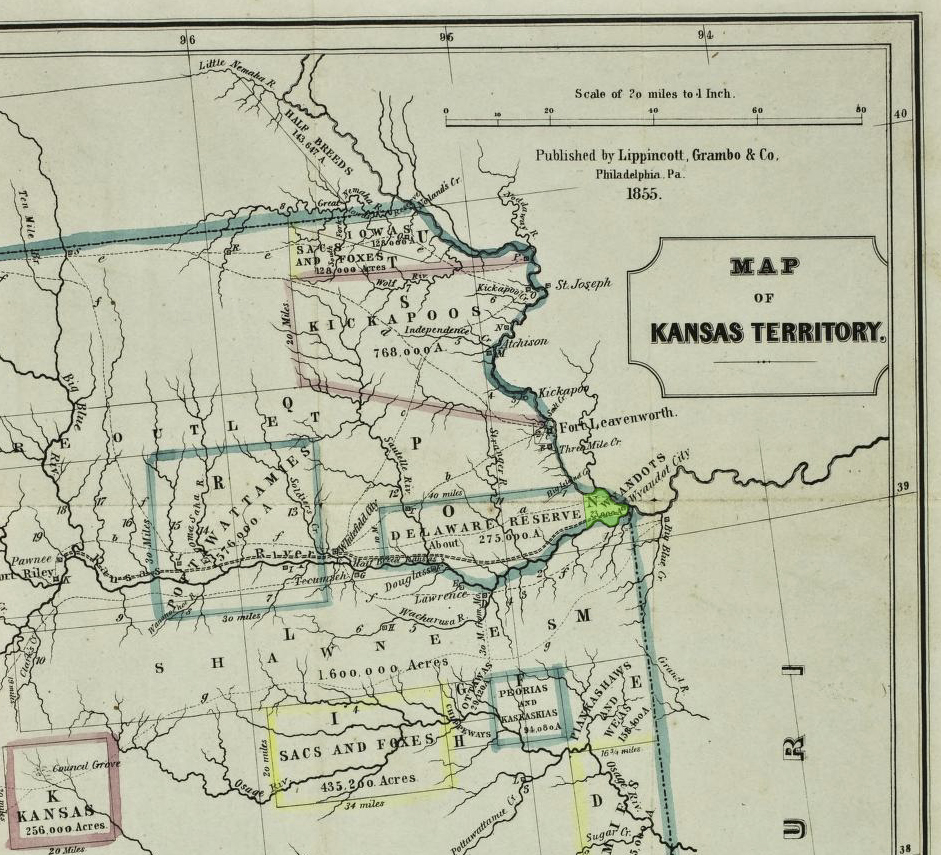

Map of eastern Kansas showing the Wyandot Purchase (highlighted in green) and Wyandot City, the Delaware on their western border and the Shawnee south of the Kansas River at that time, 1855

Several townsites were founded on the purchased land, among them Wyandot City. Armstrong was active in business, setting up a mercantile store in Westport, operating a sawmill and helping with the setup of many of early town companies within the Wyandot Purchase. Despite his success and the 1842 treaty’s promise, he had to fight for his float. Situated at the junction of two rivers, the area was prone to flooding but suitable for farming due to the richness of the soil. Consequently, he spent several years fighting squatters in court. Another issue was the belief held by some that the land had been set aside as a military reserve many years earlier by Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery. Lastly, some believed the land rightfully belonged to the Shawnee.

Map showing the approximate location of Silas Armstrong’s Wyandot Float (highlighted in pink). The separate towns of Wyandotte, Armourdale and Kansas City in the West Bottoms can also be seen, 1886

Despite the numerous challenges, a land patent for the area was issued to Armstrong in 1857. A year later, he was made head chief of the Wyandot Nation, a position he held until his death. Armstrong had located his own family farm on the land, but had much bigger ideas for its future. In 1868, the family worked with a group of investors to form the Kansas City Town Company and filed a plat the following year. Old Kansas City, Kansas, as it was later known, was poised to take advantage of the exploding livestock industry taking off in the 1870s and became home to a large portion of the Kansas City Stockyards as a result. Finally, in 1886, the towns of Old Kansas City, Armourdale and Wyandotte City were consolidated into the Kansas City, Kansas, that shares our rather peculiar border today.

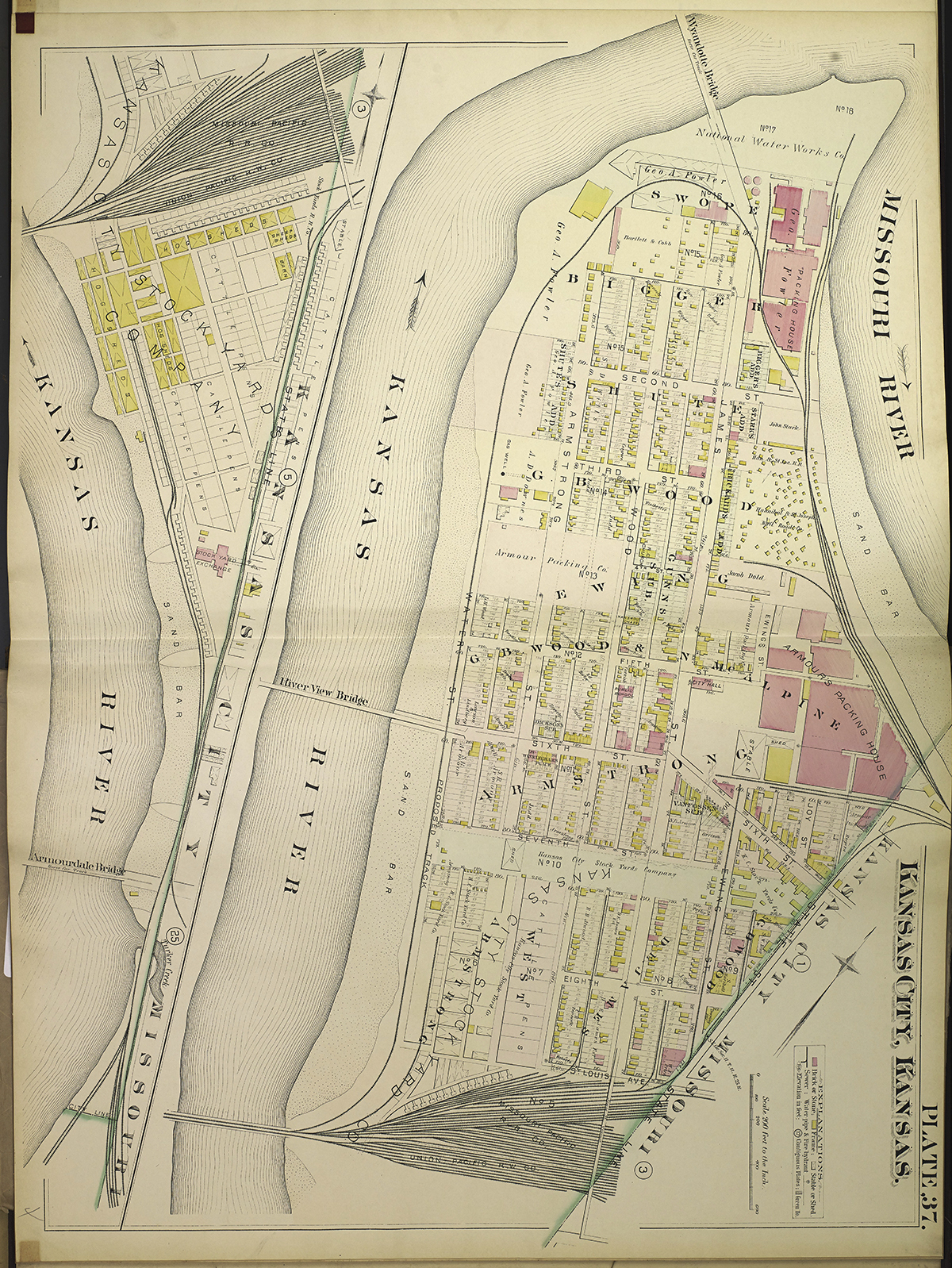

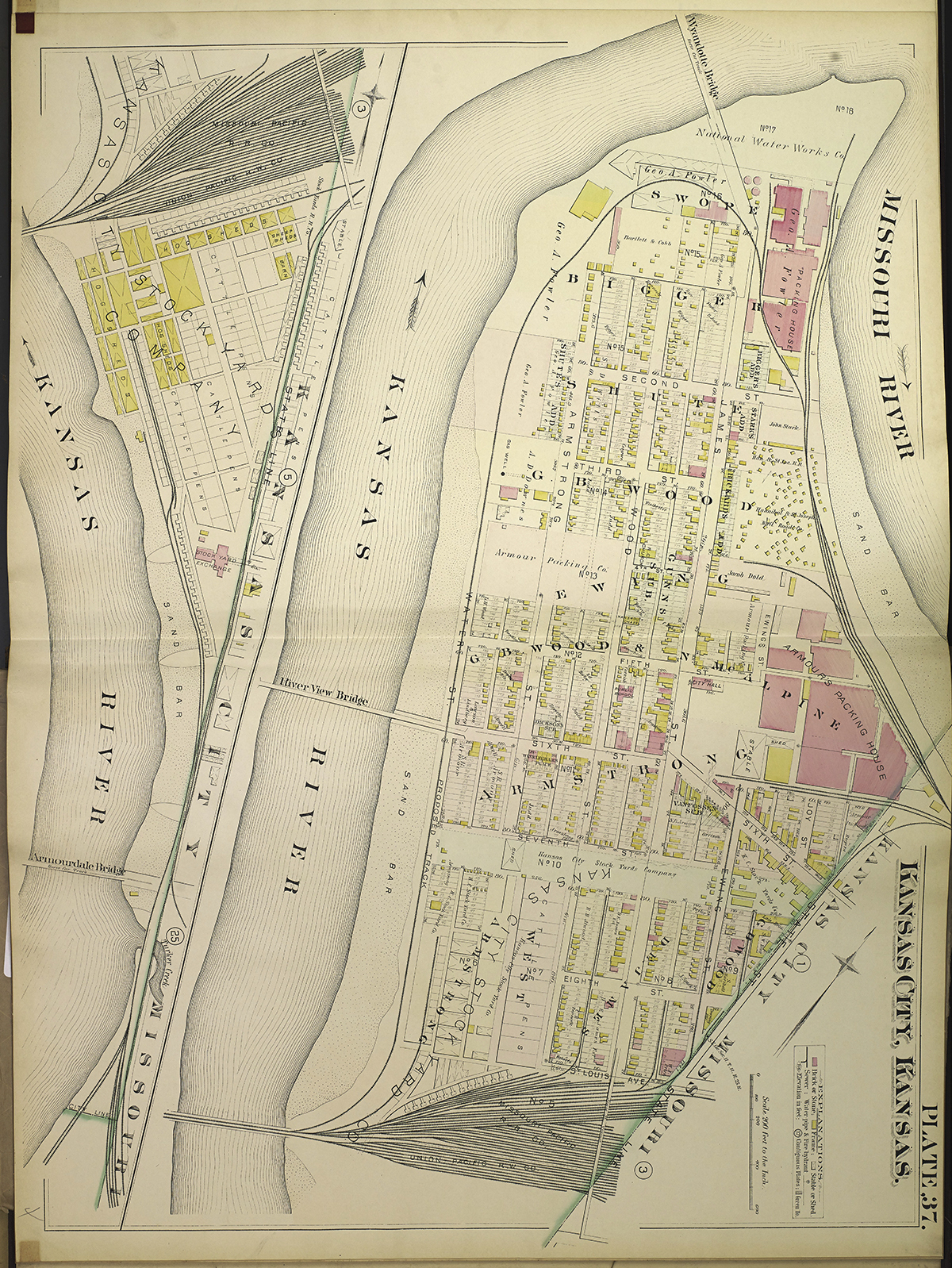

Kansas City street atlas page showing the rapid development of Old Kansas City, Kansas, due to the exploding livestock industry, 1887 (the left portion shows the southern extent of the area)

To gain an understanding of Missouri’s western border and the displacement of Native Americans, we consulted Volume 1 of William E. Foley’s A History of Missouri and Mark Stein’s How the States Got Their Shapes. We used Grant W. Harrington’s Historic Spots or Milestones in the Progress of Wyandotte County, Kansas, Homer E. Socolofsky’s article on the Wyandot Floats published in Kansas Historical Quarterly and William E. Connnelley’s article published in the March 6, 1899, issue of The Kansas City Journal to learn about the settlement of the Wyandot Nation in the area and early history of Kansas City, Kansas. The map images came from the Missouri Valley Special Collection’s Map Collection (SC117) and two Kansas City Public Library databases: American West and Fire Insurance Maps Online (FIMo). These books can be borrowed from your Kansas City Public Library branch or viewed by visiting the Missouri Valley Room at the Central Library. The databases can be remotely accessed with a current KCPL card number and PIN at www.kclibrary.org.

Map of the Kansas City area with the Kansas portion of the West Bottoms highlighted in blue, 1969

Map showing the first western and northern borders of Missouri. The border with the Osage Nation at that time is shown stretching south from Fort Osage east of modern-day Kansas City. Missouri’s northern border, beginning at the Sullivan Line and stretching east to the Des Moines River, can also be seen, 1817

Map showing Missouri’s western borders and tribal reservations set aside after the Indian Removal Act, 1836

Map drawn by William E. Connelley to illustrate the differences between Brown’s 1823 meridian line where it would have been placed based upon the location of the Kaw during the 1855 survey of the Kansas-Nebraska Territory, 1884

Map showing the Platte Purchase in northwest Missouri, 1838

Daguerreotype portrait of Silas Armstrong, n.d., image courtesy of Kansas Room Special Collections, Kansas City Kansas, Public Library

Map of eastern Kansas showing the Wyandot Purchase (highlighted in green) and Wyandot City, the Delaware on their western border and the Shawnee south of the Kansas River at that time, 1855

Map showing the approximate location of Silas Armstrong’s Wyandot Float (highlighted in pink). The separate towns of Wyandotte, Armourdale and Kansas City in the West Bottoms can also be seen, 1886

Kansas City street atlas page showing the rapid development of Old Kansas City, Kansas, due to the exploding livestock industry, 1887 (the left portion shows the southern extent of the area)