All Library locations will open late Friday, February 27 at 11 a.m. due to an all staff meeting.

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Jeremy Drouin

It’s a story that has become a part of Kansas City baseball lore: a local team enlisting famed frontier lawman Wild Bill Hickok to umpire a game against a heated rival.How much, if any of it, is true? After listening to a Library audiobook version of Tom Clavin’s Wild Bill: The True Story of America's First Gunfighter, reader and Wild West enthusiast Robert Sholar put the question to What’s Your KCQ?

The answer: It’s a questionable call.

The year was 1866. Baseball had taken root in the western part of the U.S. in the years immediately following the Civil War. The Antelopes, Kansas City’s first baseball team, were rivals of the Pomeroys of Atchison, Kansas.

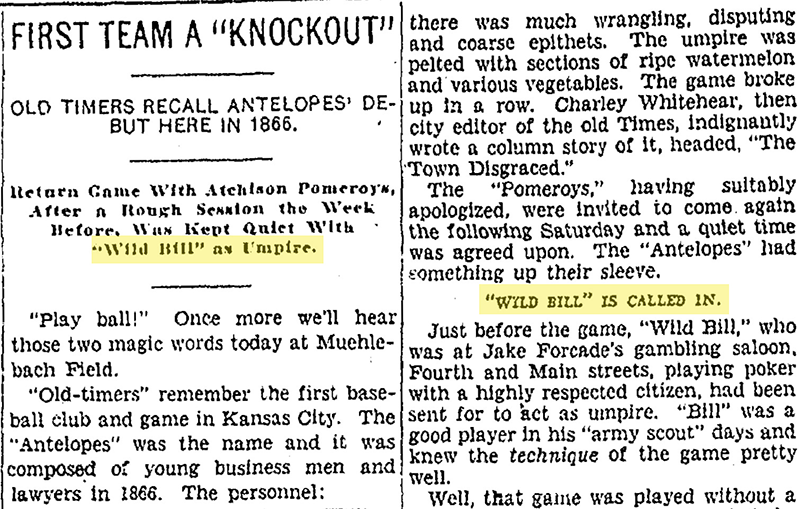

According to various published accounts, the clubs played two initial games with each winning convincingly on its home field. The second contest in Kansas City was marred by “wrangling, disputing and course epithets” as the game began to slip away from the visiting Pomeroys, and devolved to the point of the umpire being pelted with fruits and vegetables.

“THE TOWN DISGRACED,” read the next day’s headline in The Kansas City Daily Times.

After an apology from the Pomeroys, they were invited to play a decisive third game in Kansas City the following Saturday. To avoid the ruckus of the previous contest, the hometown Antelopes recruited Hickok to keep the peace and serve as umpire.

The Antelopes won decisively, 48-28, and the game was played without incident or dispute. After all, who would argue calls with a notorious gunfighter?

In return for his service, Hickok requested two white horses to pull him by carriage to Jake Forcade’s saloon at Fourth and Main streets in the Market Square.

Similar versions of this account have been published in newspapers, baseball history books, and biographies of Hickok.

But as one of his contemporaries, Mark Twain, once said, “Never let truth get in the way of a good story.” Getting to the truth of our city’s history – and the suspected intersection of its early baseball history and Wild West past – KCQ is compelled to signal foul on several key details. There’s doubt, in fact, that games between the Antelopes and the Pomeroys ever happened.

Where the Antelopes Play

Kansas City’s first organized “base ball club” was established by group of young businessmen and lawyers in July 1866. They called themselves the Antelopes for their fleetness in running the bases. Prominent attorney D.S. Twitchell was club president and William Warner, later a city attorney, mayor, and U.S. senator, served as vice-president.

Games were played on grounds in McGee’s Addition south of 14th Street between McGee and Oak (the current site of the Sprint Center). Early contests were intramural among club members who showed up to play and split into “nines.”

Soon, other clubs emerged to challenge the Antelopes. The Hope baseball club was their main rival for the city championship. Other local opponents included the Enterprises and Hectors.

The Antelopes also hosted and traveled to play Saturday games with teams from other nearby towns. An early opponent was the Frontier club of Leavenworth, Kansas, which issued public challenges to teams on both sides of the state line. The two squads played a home-and-home series in November 1866, each winning on the road.

The final scores – 67-37 and 47-24 – were unfathomably high by modern baseball standards. Rules at the time allowed a batter to call for a high or low pitch from the opposing hurler, who then tossed it underhand. Hitters had an additional advantage in that gloves were not yet part of the game, so balls in play were fielded with bare hands.

Notices of Antelope games and meetings in 1866 were published in the Kansas City Daily Journal of Commerce. Missing from the newspaper archives, however, are contests between the Antelopes and Atchison Pomeroys.

There is good reason: The Pomeroys didn’t exist as a club in the 1860s.

The first team in Atchison, the Ad Astras, was established in 1867. Not until 1885 did a club called the Atchison Pomeroys appear in the sporting news of Kansas newspapers – nearly a decade after Hickok was shot and killed while playing poker in a saloon in Deadwood, South Dakota. Could it be that Hickok umpired an Antelopes game against the Leavenworth Frontiers in 1866 instead of the Pomeroys? News reports from that year make no mention of an appearance by Wild Bill in a baseball game or bad blood between the Antelopes and the Frontier club. Not only were the games casual contests played by prominent citizens, they were usually followed by festive banquets with drinking, toasts, and speeches.

The Antelopes reorganized in 1867 for another season. But by 1868, many of the players had joined other teams and the club eventually dissolved.

Wild Bill in Wild Kansas City

Hickok became a national figure in 1865 with his pistol duel on the streets of downtown Springfield, Missouri, with a fellow gambler, Davis Tutt. In the shootout, Tutt was hit in the side and died. When Harper’s New Monthly Magazine published a highly sensationalized story about Hickock in 1867, the legend of “Wild Bill” and his gunfighting prowess was born.

Hickok was appointed a deputy U.S. marshal in 1866 and tasked with tracking down deserters and horse thieves from Fort Riley in Kansas Territory. His duties as marshal frequently brought him to Fort Leavenworth, and from there to Kansas City.

Wild Bill felt right at home in the rowdy boomtown on the edge of the western frontier, frequenting its saloons, gambling houses, and brothels – in many cases, finding all three vices under one roof. His reputation as a gunfighter already well known, Hickok was a celebrity upon arrival in the city, and an eager public was anxious to see him in action.

In a 1933 biography, Wild Bill and His Era, historian William Connelley places Hickok in Kansas City around 1866-67. He describes throngs of people waiting for him to arrive by steamboat and an anticipated showdown with a local ruffian and former member of William Quantrill’s raiders, Jim Crow Chiles. To the disappointment of the many onlookers, the two pistoleers exchanged brief pleasantries about their border war days rather than gunfire.

Connelley’s biography is the first to include the story of Wild Bill umpiring a baseball game between the Kansas City Antelopes and Atchison Pomeroys. The author calls Hickok a baseball enthusiast and an “authority of the technique of the game as played in that day.” While Connelley does not provide sources for the detailed account of Wild Bill’s role as umpire, his version of the event mirrors that of an April 28, 1927, article in The Kansas City Times headlined “First Team a Knockout.”

Published 61 years after the supposed game took place, the article relies on the memories of “old-timers” who fondly recalled Kansas City’s first baseball team in 1866. It mentions the club’s first officers, early games played at 14th and McGee, and passionate fans flocking to games on Saturdays to root on their hometown team.

And yes, in that account, Wild Bill makes a grand appearance as umpire in a game between the rival Antelopes and Pomeroys.

However, another Times article about the Antelopes published 20 years earlier, in 1908, provides a more reliable perspective. In the story, former Antelopes player and club secretary W.H. Winants recounts when the team was pride of the city in 1866 and the many prominent citizens who made up the ball club.

Winants describes games with the Leavenworth Frontiers as “red letter events” that drew large crowds. When the Antelopes traveled to Leavenworth, the town was “thrown open” to the visiting players. “No matter want we wanted – a cigar or a shirt collar – it was handed out and payment declined,” Winant said about the hospitality of the local merchants.

Noticeably absent from Winants’ recollections of former Antelopes glories is a rivalry with an Atchison ball club or mention of Wild Bill Hickok umpiring a game. The presence behind the plate of one of the most notorious gunfighters of the American West would seemingly be a story worth sharing with a reporter – if it had indeed taken place.

The Call at the Plate

The available evidence suggests the Wild Bill Hickok story being a tall tale rather than historical fact. While the specific details of the 1927 newspaper account seem to lend credence to the story,, there are too many inconsistencies to overlook.

Newspaper reports from the period point to the Leavenworth Frontier baseball club, not the Pomeroys of Atchison, as the Antelopes’ rival from Kansas. Games between the two teams were collegial, with each city putting its best foot forward to graciously host the visiting opponent – a far cry from the unruliness and vegetable throwing detailed in the 1927 article and subsequent accounts.

A key piece of information missing from the Hickock umpiring claim is an article known to have run in The Kansas City Daily Times, headlined “A Town Disgraced.” The newspaper was published from 1868-1872 before becoming The Kansas City Times. But archival records date only to 1871, a few years after the Antelopes club disbanded.

While the possibility of Wild Bill Hickok having some involvement in a baseball game in Kansas City in the 1860s or ’70s cannot be completely ruled out, the research suggests that the umpiring story – perpetuated for nearly a century – is at the very least far-fetched, if not outright fiction.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.