Library History

One of the most significant occurrences in Kansas City's leap from a country town to a thriving metropolis was the building of a permanent public library.

Kansas City Public Library was founded December 5, 1873, in an untamed western town still recovering from the social and economic strife of the Civil War. Rapid growth in population and industry outstripped the city’s efforts to provide public education and other resources for civic progress. A public library would prove crucial in the city’s transformation into a great metropolis on the plains.

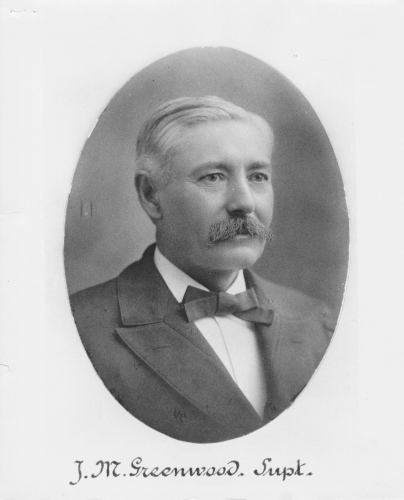

The Library was founded as part of the city’s school district and would continue to provide both school and public library services for the next 115 years. Initial fundraising efforts resulted in the purchase of a bookcase and around 100 books, including the American Encyclopedia. In 1874, the school board hired James M. Greenwood as superintendent of schools. The book collection resided in district offices in a high school building at 11th and Locust Streets and could be accessed by teachers and students. Two years later, Greenwood began lending books to the public from his own offices in the Sage Building at 8th and Main Streets. For two dollars a year, a subscription service allowed patrons to check out one book at a time. The Library added its first periodicals to the collection in 1879, and during the same year it moved with the school district headquarters into the Piper Building at 546 Main Street.

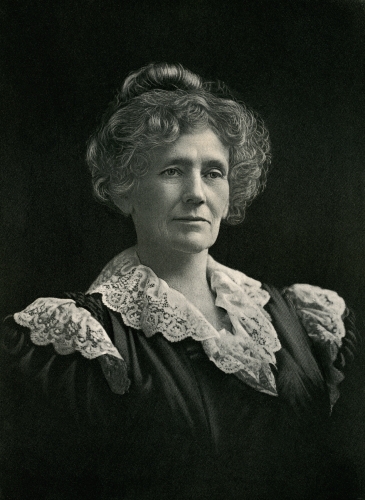

In 1881, the district hired Carrie Westlake Whitney to serve as the system’s first full-time head librarian. Over the next three decades, Whitney’s leadership resulted in free book lending to the public, a unique emphasis on children’s literacy, two purpose-built Main Library facilities, two museums, and the Library’s first branch, the Westport Branch, in 1899. The latter remains the oldest branch still operating today.

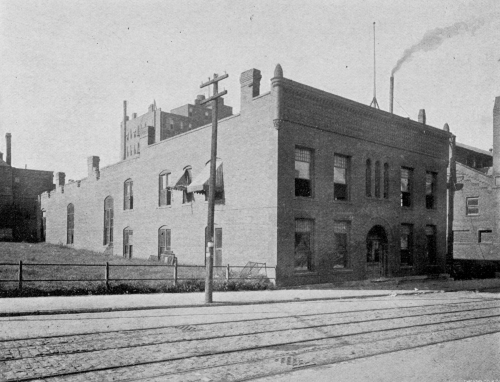

In 1884 the Library moved into another existing building at 8th and Walnut Streets, and, for the first time in 1889, it moved into a purpose-built structure at 8th and Oak Streets in 1889. Even the $10,000 Oak Street building soon proved inadequate to serve the bustling community.

In 1897, the Library moved to a grander facility at 9th and Locust Streets. In addition to its circulating book collections, the $200,000, marble-clad Second Renaissance Revival building housed the Nelson Gallery of Art, the direct predecessor to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. The Library also operated an anthropology and natural sciences museum, which later contributed the first 40,000 artifacts to collections at the Kansas City Museum. Whitney additionally oversaw the creation of a dedicated children’s reading room that is considered one the earliest of its kind in the United States. The Library’s circulating and reference collections grew to nearly 100,000 books by 1910.

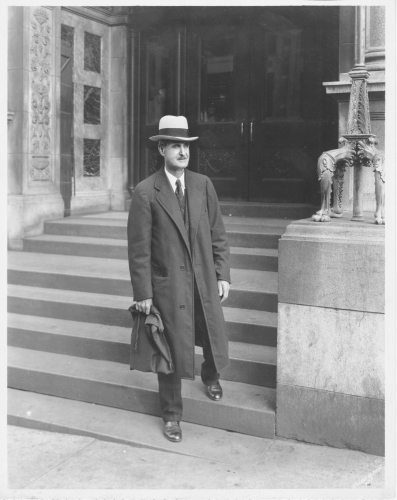

Between 1910 and 1912, the school board demoted Whitney to assistant librarian and hired Purd Wright as head librarian. In doing so, members of the board followed a trend of placing men in charge of growing public library systems in major cities across the country.

For his part, Wright qualified for the position as the widely recognized founder of the St. Joseph Public Library and recent director of the Los Angeles Public Library. By the time that Wright retired in 1936, the Library had added 20 public library branches, mostly located in schools and community centers to maximize geographic reach with economic efficiency. During Wright’s time as director, annual book lending reached 1 million in 1922 and 2 million in 1931.

Amid this era of rapid growth, the Library supported national efforts in both World Wars, headlined by more than 170 Library alumni serving in the armed forces during World War II. The Library also led campaigns raising thousands of dollars for war bonds and to circulate tens of thousands of donated books to military posts regionally and overseas. The steady progress was punctuated in the interwar period by the financial effects of the Great Depression and debates over a national wave of censorship and book banning. Nonetheless, 44 percent of Kansas City’s population held library cards by 1944, the highest among large cities in the nation.

During the post-World War II era, librarians who had so strongly opposed fascism went on to contest domestic movements to ban or censor books. The Library began supporting the American Library Association’s (ALA) Banned Books Week and later signed on to the ALA’s Freedom to Read Statement and Library Bill of Rights in 1984.

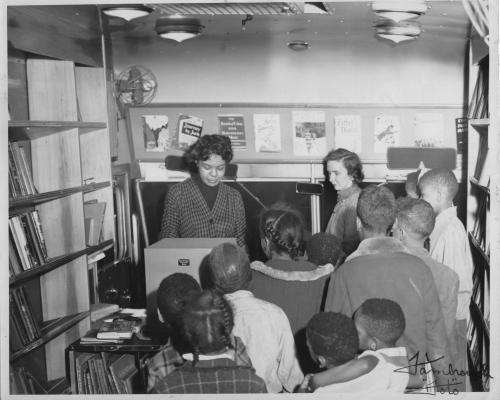

Expansions continued with the opening of a new Main Library (at 12th and Oak Streets) in 1960 and the original Plaza Branch (at Brookside Boulevard and Main Street) in 1967. The Main Library contained the original Missouri Valley Room, where visitors could utilize collections in local history and genealogy. The architecture of both the Main Library and Plaza Branch nodded toward the impact of changing technologies on librarianship and shifting community needs. Across generations, the Library continued to embrace innovations, from player piano rolls and telephone renewal services in the 1910s to its first bookmobile in 1950 and its first network-connected database in the 1970s.

By the mid-20th century, the placement of most of the Library’s branches inside public schools had resulted in service gaps to minority communities, and the Library drew criticism from local media and national library trade journals. Efforts to become more inclusive eventually led to a full reorganization of the branch system from the late-1980s to the early 2000s. Of special note was the opening of the Lucile H. Bluford Branch in 1988 (named for the renowned Civil Rights leader and editor of The Kansas City Call) and the renaming of the Irene H. Ruiz Biblioteca de las Americas Branch (for the prominent West Side librarian in 2001). These measures were overseen by Library Director Daniel J. Bradbury, who also guided the Library through its separation from the Kansas City Board of Education in 1988.

Under Director Crosby Kemper III, who served in that capacity from 2005 to early 2020, the Library expanded its commitment to public programming, technology services, refugee and immigrant services, and community outreach. Recognizing these developments, Representative Emanuel Cleaver II successfully nominated the Library for the National Medal for Museum and Library Service in 2008. The Library became one of the earliest in the nation to eliminate late fees with its Freedom from Fines policy in 2018.

Today the Library operates the Central Library in the historic First National Bank Building at 10th and Baltimore, nine branches, online services, and the Bookmobile.

To learn more about the Library’s history, read Kansas City’s Public Library: Empowering the Community for 150 Years.

Historic Main/Central Library Locations

- 11th & Locust: 1873-1874

- 8th & Main: 1874-1878

- 5th & Main: 1879-1884

- 8th & Walnut: 1884-1889

- 8th & Oak: 1889-1897

- 9th & Locust: 1897-1960

- 12th & McGee: 1960-2003

- 10th & Baltimore: 2004-present

Historic Branch Locations (sorted by opening date)

- Westport (formerly the Allen Library, Westport): 1898 to present

- Switzer (Switzer School): 1911-1936

- Swope Settlement: 1913-1943

- Jewish Institute: 1913-1936

- Louis George (25th and Holmes): 1913-1965

- Northeast (Northeast High School): 1914-1986

- Garrison Square (Garrison Square Field House): 1914-1922

- Swinney (Swinney Elementary School): 1915-1967

- Central (Central High School): 1915-1986

- Karnes (Karnes School): 1916-1929

- Mark Twain (Mark Twain School): 1916-1938

- Kensington (Kensington School): 1916-1932

- Blue Valley (Jackson School): 1921-1940

- Lincoln (Lincoln High School): 1922-1967

- Washington (Mt. Washington Elementary School): 1925-1955

- Paseo (Paseo High School): 1926-1968

- West (West Junior High School): 1927-1988

- Southwest (Southwest High School): 1927-1986

- East (East High School): 1932-1986

- Center (Jewish Community Center): 1937-1961

- Southeast (Southeast High School): 1938-1986

- Blue Valley (Manchester School): 1940-1986

- Van Horn (Van Horn High School): 1955-1986

- Plaza (original): 1967-2001

- Wayne Miner Center (Wayne Miner Recreational Center): 1968-1973

- Plaza (temporary, 301 East 51st Street): 2001-2005

- Plaza (4801 Main Street): 2005-present

- Prospect (temporary): 1968-1988

- Boys Clubs (various sub-branches at the Clymer Center and on 39th, Paseo, and Thornberry): 1968-1982

- Benton: 1971-1988

- Linwood Center (Linwood shopping center): 1971-1986

- Seven Oaks (Seven Oaks shopping center): 1974-1986

- Fairmount: 1986-1989

- The Landing (The Landing shopping center): 1986-1995

- Lucile H. Bluford: 1988-present

- Waldo (formerly named South): 1988-present

- Northeast (Northeast shopping center): 1986-1989

- North-East (6000 Wilson Road): 1989-present

- Trails West (Independence): 1989-present

- Southeast (Waldo Shops at 75th and Wornall): 1986-1988

- West (902 Southwest Boulevard): 1988-1995

- West (525 Southwest Boulevard): 1995-2000

- Southeast (63rd & Swope Parkway): 1996-present

- Sugar Creek: 1996-present

- Irene H. Ruiz Biblioteca de las Americas: 2001-present