This story first aired on KCUR.org on October 17, 2025. Listen here.

Author Enfys McMurry says, when she started writing about the crash of Continental Airlines Flight 11, she struggled with the story's structure.

“For some reason, I want to write history in the present tense,” says McMurry.

While the tragedy she writes about took place 63 years ago, McMurry examines the event minute by minute, starting on May 22, 1962.

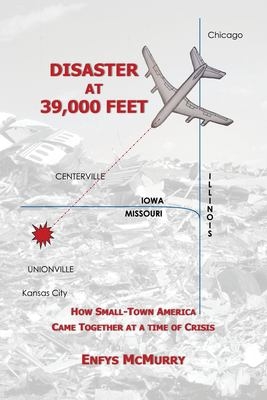

That night, aviation officials lost radar contact with the Boeing 707 near the Iowa-Missouri border during a routine flight from Chicago to Kansas City.

A loud bang was heard in the sky. Shortly after, airplane debris was scattered across fields and roads between Centerville, Iowa, and Unionville, Missouri, near where the wreckage of the plane eventually landed.

Eight crew members and 37 passengers died.

“When people say it was the deadliest of crashes, it's much more than that,” McMurry says. “There had been bombs put on aircraft. Only this one is the very first in a jet luxury passenger airliner.”

Air travel in the 1960s was very different from today, she says. This particular flight was known as the “champagne flight,” for instance, and there were virtually no security checkpoints at the airport.

In her book, “Disaster at 39,000 Feet: How Small-Town America Came Together at a Time of Crisis,” McMurry reconstructs the day of the crash and the days afterward through newspaper articles, her own interviews, and Federal Bureau of Investigation records.

“When I contacted the FBI, I asked if they would give me any information,” she says. “They sent me 800 pages of the official report.”

The documents are heavily redacted, but “of course, (with) every FBI interview there's a precise time,” McMurry says. “So it became logical, what happened before, what happened after.”

McMurry, a native of Wales and a U.S. citizen for more than 30 years, lives in Corydon, Iowa, about 24 miles from Centerville. Her book details the search and rescue efforts by first responders, aviation officials, and citizen volunteers in Missouri and Iowa.

After the crash left a 40-mile trajectory of aircraft debris, “dozens of people are out,” McMurry says.

“They’re on both sides of the road. They’re in the fields. They’re carrying flashlights, moving like fireflies through the dark,” she says. “They’re picking up paper napkins, a spoon, a knife, pieces of metal.”

Some drove to the crash site and pointed their truck headlights at the downed aircraft so the local doctor could identify any survivors.

For many residents and their families, the tragedy has had a lasting impact, she says.

“When devastation like this occurs, I felt as though a depression settles over the community,” McMurry says. “They deal with it. They encourage. They rush to help the other human being — which moves me.”

As officials worked to pinpoint the cause of the crash, some familiar names show up in the pages of McMurry’s book, including Mark Felt, who led the FBI team in Kansas City at that time. Felt worked for the FBI from 1942 to ‘73 and later gained fame under the pseudonym “Deep Throat” as a whistleblower during the Watergate scandal.

“Their first job was to identify the people who were dead using fingerprints, and fingerprints from bottles and people's homes. And they did it all so rapidly and so efficiently,” McMurry says.

Identifying the cause of the crash required meticulously reassembling the aircraft's tail section, and had FBI agents crawling on their hands and knees through the wreckage.

“At one stage, an FBI officer, a special agent, crawling across the ground there, lifted a piece up, smelled it, and looked at everybody and said, ‘fireworks,’” McMurry says. “They knew that this was dynamite.”

Officials reviewed the passenger records, revealing several who purchased insurance for the flight between Chicago and Kansas City. One stood out: Thomas Gene Doty, of Merriam, Kansas.

McMurry says the image of Doty that emerges from FBI files is of a once-successful businessman, husband, and father whose life took a sharp turn.

“His business vault company burned down, and his patents all were absorbed by another funeral home, and when he went to court, he lost that case,” she says. “Then comes the spiral, down, down, down.”

When Doty boarded the flight, he brought six sticks of dynamite with him. He placed them in the aircraft’s rear bathroom, and the explosion caused the plane to break apart mid-flight.

“Apparently not a whit of conscience for all those people that he decided to take (with him) as a way of ending his life,” McMurry says.

Enfys McMurry will discuss her book “Disaster at 39,000 Feet: How Small-Town America Came Together at a Time of Crisis” at 2 p.m. on Sunday, Oct. 26, at the Kansas City Public Library’s Central Library, 14 W. 10th St., Kansas City, Missouri 64105. RSVP here.