KCQ: Amid a tide of racism, a legendary boxer celebrated a triumphant week in Kansas City

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Dan Kelly | Kansas City Star

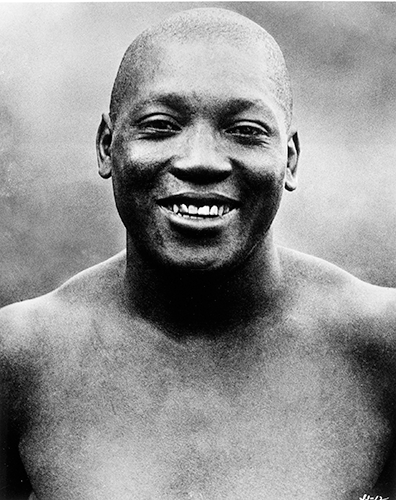

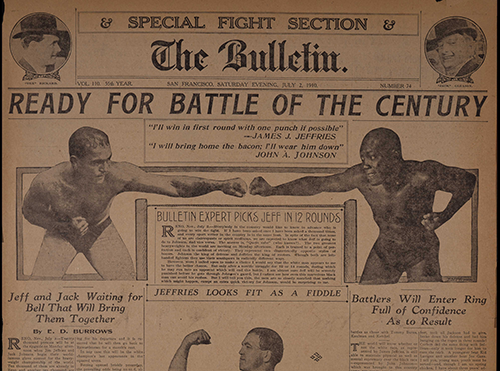

Jack Johnson was one of the most famous people in the world in February 1912, having pummeled Jim Jeffries 19 months earlier in the “Fight of the Century” to retain his world heavyweight boxing championship.

“The Galveston Giant,” who had become the first Black heavyweight champion in 1908, raked in thousands of dollars just for stepping on theater stages. He spent just about every dollar on cars, clothes and anything else that supported his lavish lifestyle. Newspaper reporters followed him everywhere, writing about his every step and, especially, his missteps.

In that racist Jim Crow era, the champ was despised and resented by most white Americans, largely because of his affinity for white women. His victory over Jeffries had been met with race riots around the nation, and Johnson was the target of unrelenting death threats and racist attacks.

Meanwhile, the government attempted to do what no white boxer could — take down the brash Black man.

shows in seven days at the Century Theater, now the Folly. | Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Amid it all, Johnson spent a week in Kansas City — and there were no reports of any violence or disruptions. Quite to the contrary: Johnson was a big hit.

That week was the basis for Stuart Carden’s query to “What’s Your KCQ?,” The Star’s ongoing series with the Kansas City Public Library that answers readers’ questions about our region:

"I have heard that Jack Johnson, the first Black heavyweight champion of the world, fought at the Folly Theater. And may have even stayed in an apartment above the stage when turned away from hotels because he was traveling with his white girlfriend. What’s the history of Jack Johnson, Kansas City and the Folly?"

As artist director of Kansas City Repertory Theatre, Carden has a rooting interest in Johnson’s Kansas City connection. KC Rep’s production of “The Royale,” a drama inspired by Johnson’s story, will open March 8.

The play’s protagonist, named Jay Jackson, is a Jack Johnson clone — flamboyant, outspoken and unapologetic

“The piece both captures the triumph of this man but also the cost that comes along with that triumph,” Carden said.

Kansas City author and historian Phil S. Dixon calls Johnson “the most publicized African American of his era. There’s nobody close, no one close to Jack Johnson. You couldn’t miss this guy.”

Dixon has completed the bulk of a book based on Johnson’s own manuscript, written while he was a prisoner at Leavenworth after being convicted on trumped-up charges of violating the Mann Act. He was accused of transporting a woman across state lines for immoral purposes.

That episode brought Johnson to Kansas City in 1921 after his release from Leavenworth. He attended a reception here and staged two boxing exhibitions, including one at the Billion Bubble Park baseball stadium in Kansas City, Kansas. Johnson also shot scenes for a movie filmed here.

It was the last of his three boxing-related KC stays (he almost certainly had other visits) over about 25 years, with Kansas Citians seeing him during the nascent stage of his career, at his peak and in his decline.

The first was in 1898. The Star reported on July 20 that Johnson, then about 20 years old, was “open for engagements at 160 pounds against any boxer in Missouri or Kansas” and could be found at “the Olympic club, a colored organization, at Sixth and Grand.” On July 23, The Star noted that Johnson would fight a six-round bout during “a grand athletic carnival and barbecue at the Blue River park.”

Johnson beat Cherokee Tom Cox, who went on to become a well-known trainer, on July 24, 1898, in what was unofficially the future champ’s third professional fight.

Great White Hope,” on July 4, 1910, in the “Fight of the Century.” | Gary Phillips Collection

Tale of the Century

Johnson’s Kansas City visit of Feb. 25-March 2, 1912, was his most notable, coming as it did after he beat Jeffries, “The Great White Hope,” a nickname that inspired a Broadway play and 1970 movie.

First, some clarifications about Carden’s query.

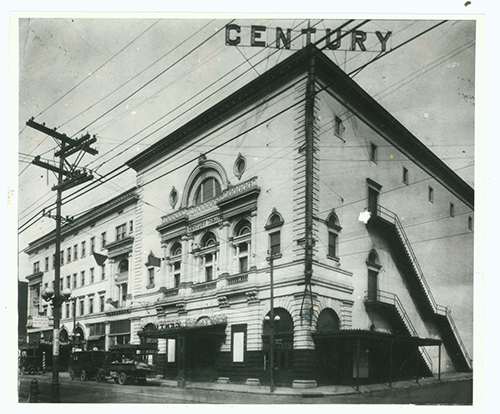

The theater was not yet the Folly; it was the Century, after having opened in 1900 as the Standard.

And it would be a stretch to say Johnson “fought” there. He appeared as part of a vaudeville show that also included two comic operas and a cycling act billed as the Tortoni Troupe.

Johnson sang, played cello and addressed the crowd in addition to sparring three one-minute rounds with the feckless Marty “Kid” Cutler, his regular training partner who won just one of his 22 professional fights and went on to become a pro wrestler.

Record crowds showed up at the Century despite a snowstorm that week. Johnson’s take was $2,500 — for two shows a day over seven days — at a time when the average income in the United States was less than $750 a year.

Joe Donegan, manager of the Century, had pursued Johnson over the previous two years. The champ was set to appear March 20-21, 1910, in what was scheduled to be his final public appearance before going into training for his famous July 4 bout with Jeffries.

Johnson was a no-show, however. The response from Donegan, a Pendergast crony known as the “Angel of Twelfth Street” because of his charitable treatment of poor showgirls, was far from divine.

“I’ve always been an ardent admirer of the renowned Abraham Lincoln,” Donegan said, “and never have I borne an ill feeling toward the Negro race. But if our illustrious martyred president was in any way responsible for the present freedom of Jack Johnson, then friendship between ‘Abe’ and me ceases from this minute.”

It turned out Johnson’s lawyers had advised against his trip to Kansas City because he had a March 23 court date in New York on an assault charge. In fact, he wound up spending part of that day in Manhattan’s infamous jail called “The Tombs.”

It was there that Johnson was served notice of a lawsuit for breaking his contract with Donegan.

“I don’t see how I could appear on the stage there when I’m in jail here,” Johnson told The New York Times. “Guess I’ve got a good defense.”

Of course, he hadn’t been in jail on the days he was supposed to have performed at the Century.

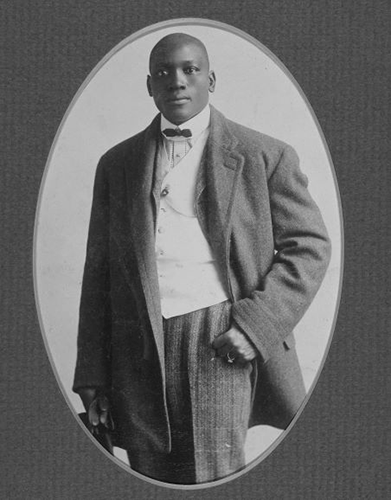

Johnson was known as a sharp dresser throughout his life. | File Photo

Boulevard dreams

Donegan and Johnson apparently resolved their differences, although the snow did put a crimp in the champ’s 1912 visit.

At a time when fewer than 1 in 100 Americans owned cars, Johnson boasted a fleet of them. He liked to bring two when he was on the road, and he was looking forward to testing them on Kansas City’s nationally famous boulevard system.

“I have heard so much about your many miles of boulevards, and now that I am here I am going to inspect them,” he said. “I want to see for myself how easy my Firestone tires will roll over your pavement. I think that I will be able after that to endorse the many fine things I have heard about the boulevards.”

Unfortunately, the blizzard hindered his ability to drive in Kansas City.

“Just think how miserable Kansas City has treated me,” he said. “Ever since I’ve been here it has either snowed or the ground has been covered with snow.

“Unless this snow clears away, however, I will have to store the machines and adopt the snowshoe route.”

Most of these Johnson quotes came from The Kansas City Post, where Otto Floto, one of the nation’s most popular and colorful sports writers, was sports editor at the time. Floto, who spent most of his journalism career in Denver, also was a showman — he operated an actual dog-and-pony show — and it was reflected in his writing as well as his name.

Floto, like other writers of the time, referred to Johnson in terms ranging from demeaning to offensive to blatantly racist.

Among the nicknames that found their way into print were “Big Cloud,” “Black Smoke” and “Lil’ Athuh” (his middle name was Arthur). The Star described him as the “the gigantic negro,” the “colossal cinder” and worse.

Johnson typically smiled at the insulting language and frequently returned the favor. Of his upcoming opponent Jim Flynn, he told Floto, “He is easily the best man the pale-faced race boasts of at this time.”

as the Standard Theater on Sept. 13, 1900. | Folly Theater

Suite science

The lodging portion of the Century story is difficult to pin down.

Johnson and Etta Duryea, his wife whom The Star described as “a big voluptuous blond with a pink plumed hat,” were refused by local hotels. Most accounts indicate they stayed in a suite in the theater, perhaps overlooking the stage, that was used by Donegan or Century owner James Butler.

“When the African American boxing champion Jack Johnson performed at the Century in February 1912, Johnson and his white wife could not stay as registered guests in the hotel proper, so Donegan put them up in Butler’s old suite with the view of the stage,” writes Felicia Hardison Londré, a theater professor at University of Missouri-Kansas City, in her 2007 book “The Enchanted Years of the Stage: Kansas City at the Crossroads of American Theater, 1870-1930.”

Other accounts suggest the apartment was not in the theater but in the adjoining Edwards Hotel.

Brian Williams, the Folly’s development director, said, “There have been stories that there was a suite that Butler had built in the hotel next to the theater that had kind of a secret passageway into the boxes, so he could stay at the hotel and kind of slip into the theater kind of surreptitiously.”

The closest thing to a primary source on the issue is the Folly’s successful 1974 application for National Register of Historic Places status, which relied on the memory of Donegan’s widow, Rose. Mind you, this was 62 years after the actual events.

It reads: “Jack Johnson and his wife stayed in the owner’s apartment in the theater during his visit to Kansas City, as no hotels would rent him a room.”

The application also mentions that “the owner’s mezzanine apartment” was removed in 1923.

History lesson

Dixon provided yet another tie between Johnson and Kansas City.

Johnson’s only sister, Lucy, married Otto Bolden, who played for several Negro Leagues baseball teams, including the Kansas City Giants. The couple married at Jack Johnson’s Chicago house in 1910 but lived in Kansas City, so it seems likely Johnson visited them here.

Bolden died in Kansas City in 1930 and is buried locally. Lucy moved to Chicago, where she died in 1962 at the age of 90 from burns suffered after her clothing apparently caught fire while she was smoking.

Jack Johnson’s death in 1946 provided the last of the many racial affronts he suffered. After he crashed his Lincoln Zephyr on a rural North Carolina road, a white ambulance driver refused to give him aid and Johnson was taken to a segregated hospital, where he died.

You can’t read about that in any history books, of course. Or much else about Jack Johnson for that matter.

“I would be willing to say most young Black people have never heard of Jack Johnson,” Dixon said.

“He was not politically correct, so when they talk about the people in Black history, the Booker T. Washingtons, the Frederick Douglasses, and even when they went to sports, they would go to Jackie Robinson quicker than they would go to Jack Johnson. So Jack Johnson is the man out.”

Still, Dixon would rank Johnson among the most famous Black people from the past.

“Let’s say we put him in the top 10 with people like Frederick Douglass or Booker T. Washington,” he said. “But you’ve got to have Jack Johnson in there, probably the earliest one for sports.

“He opened the door for a lot of conversation, especially interracial marriage. He opened the door wider than anyone had up to that point.”

Epilogue

July 4, 1912: Johnson retained his title by beating Jim “The Fighting Fireman” Flynn in Las Vegas, New Mexico; afterward, huge crowds greeted him at train stations in Dodge City, Hutchinson, Emporia and Topeka en route from New Mexico to Chicago.

Sept. 11, 1912: Johnson’s wife, Etta Duryea, died by suicide committed suicide in Chicago., shooting herself in the head.

Oct. 22, 1912: Mayor Henry Lee Jost barred Johnson from any more vaudeville appearances in Kansas City.

Dec. 4, 1912: Johnson married Lucille Cameron, a white former prostitute from Milwaukee; public outrage ensued. Gov. Cole Blease of South Carolina called for the “black brute who lays his hands upon a white woman” to be lynched.

May 13, 1913: Johnson was found guilty of violating the Mann Act; he eventually fled to Europe to avoid prison.

April 5, 1915: Jess Willard, a 6-foot-6 Kansan billed as the Pottawatomie Giant, defeated Johnson, then 37, in Havana, Cuba, to take his title.

May 24, 2018: President Donald Trump pardoned Johnson.

The Royale

The play, written by Marco Ramirez, runs March 8-27 at Kansas City Repertory Theatre’s Copaken Stage downtown. The following free performances will be held at Kansas City Public Library locations:

- Sunday, April 3, 2 p.m., at North - East Branch

- Tuesday, April 5, 6 p.m., at Central Library

- Friday, April 8, 2 p.m., at Bluford Branch

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.