Central Library has a new parking validation process.

Lucile Bluford – namesake of the Library's L.H. Bluford Branch at 3050 Prospect – was a local civil rights leader and helped The Kansas City Call become a vital source of news and information for the Black community. The Library celebrates Bluford’s impact on city and the nation at large on Lucile Bluford Day, celebrated across Missouri on July 1 per a 2016 measure signed into law that encourages residents to "appropriately observe the day in honor of Lucile Bluford, a journalist and civil rights activist who successfully sued to end segregation in the University of Missouri journalism program and whose long and distinguished career at The Kansas City Call contributed to it becoming one of the largest and most important Black newspapers in the nation.”

The Kansas City Call employees in front of the newspaper’s offices with Lucile Bluford at center, ca. 1930s. (Image courtesy The Kansas City Call)

Biography

Born in North Carolina in 1911, Lucile Bluford moved with her family to Kansas City when she was 7. She would become one of its most accomplished and beloved citizens.

She fell in love with journalism while working on the newspaper and yearbook at Lincoln High School, where she graduated first in her class in 1928. With access to the University of Missouri and its famed journalism school blocked by the school’s refusal to admit African-Americans, Bluford attended the University of Kansas, graduated with honors, and launched a reporting and editing career that eventually took her to The Call (where she’d worked summers during college).

She continued to push back against MU’s segregation policy. Backed by the NAACP, Bluford repeatedly applied for admission to its graduate program in journalism and filed several lawsuits. Missouri’s Supreme Court finally ruled in her favor in 1941, ordering the university to admit her because there was no equivalent program at all-Black Lincoln University. Mizzou subsequently closed its graduate program, claiming professors and students were being siphoned away by World War II.

Bluford never took a class at MU, but her fight helped nudge the school toward integration. Mizzou was forced to establish a journalism school for African-American students at Lincoln, and admitted its first Black student in 1950. The university would honor Bluford decades later, the journalism program awarding her its Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism in 1984 and the school conferring an honorary doctorate in the humanities in 1989.

Bluford went on to a 69-year career with The Call, moving from reporter to city editor to managing editor and finally editor, owner, and publisher. She made the weekly newspaper a prominent voice for African-Americans in the city and a force in the fight against discrimination.

The Library named its branch on Prospect Avenue for her in 1988. In 2002, a year before she died at age 91, the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce named her Kansas Citian of the Year.

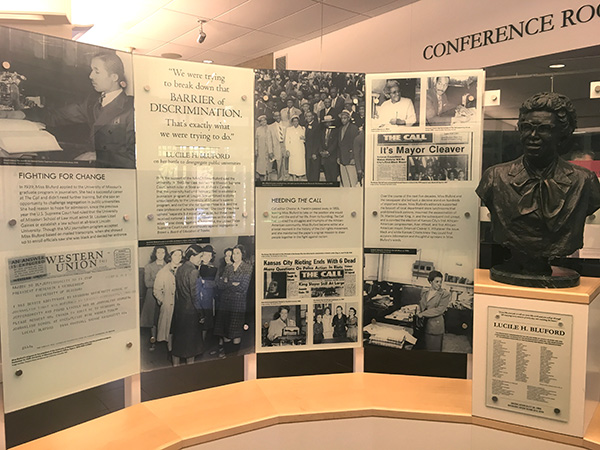

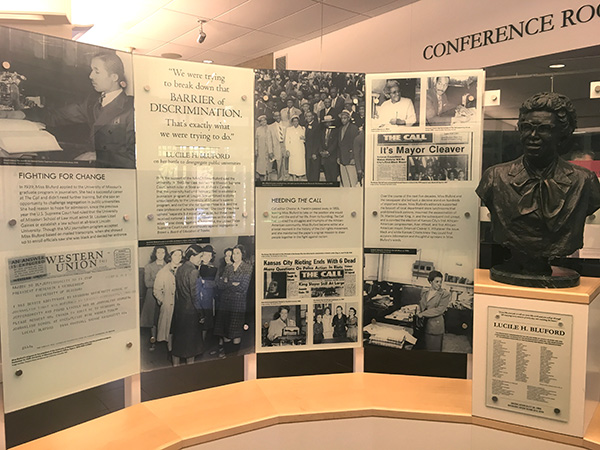

The lobby of the Bluford Branch features an exhibit about Lucile Bluford's work in civil rights and journalism.

ARCHIVED SIGNATURE EVENT

Lucile Bluford: Her National Closeup

July 11, 2018

In this Library program from 2018, Sheila Brooks examined Bluford’s life and pioneering work in a discussion of her book Lucile H. Bluford and the Kansas City Call: Activist Voice for Social Justice, co-authored with Howard University’s Clint C. Wilson II. The Kansas City-born Brooks, a former television reporter, anchor, news director, and documentary producer, recounted Bluford’s fight for admission into the University of Missouri’s graduate journalism program and assessed her dual role as a journalist and advocate for the women’s and civil rights movements.

Listen to Event Audio | Event Details | About the Book

Lucile Bluford Coloring Sheet

Lucile Bluford is among the individuals featured in Coloring Kansas City: Women Who Made History, a coloring book produced by the Library's Missouri Valley Special Collections highlighting notable women from our region's past.

About the coloring book Download the Lucile Bluford coloring sheet

Digital Court Documents

The Library's historical website The Pendergast Years: Kansas City in the Jazz Age and Great Depression has a digitized collection of documents from the National Archives at Kansas City, Missouri, related to the lawsuits that Lucile Bluford pursued against S.W. Canada, the registrar of the University of Missouri, for repeatedly denying her admission to the university. Browse the scanned documents and read some of the contextual descriptions of the materials online.

View Documents

Confronting Injustice: Lucile Bluford and the Kansas City Call, 1939-1942

The Pendergast Years site also features an original article exploring how Bluford used her role as managing editor of The Call to draw attention to her efforts to enroll in journalism classes in the University of Missouri in pursuit of civil rights for African-Americans. An excerpt:

The Kansas City Call employees in front of the newspaper’s offices with Lucile Bluford at center, ca. 1930s. (Image courtesy The Kansas City Call)

Mayor Richard Berkley presents a plaque to Lucile Bluford during the opening of the Library's Bluford Branch in 1988.

Biography

Born in North Carolina in 1911, Lucile Bluford moved with her family to Kansas City when she was 7. She would become one of its most accomplished and beloved citizens.

She fell in love with journalism while working on the newspaper and yearbook at Lincoln High School, where she graduated first in her class in 1928. With access to the University of Missouri and its famed journalism school blocked by the school’s refusal to admit African-Americans, Bluford attended the University of Kansas, graduated with honors, and launched a reporting and editing career that eventually took her to The Call (where she’d worked summers during college).

She continued to push back against MU’s segregation policy. Backed by the NAACP, Bluford repeatedly applied for admission to its graduate program in journalism and filed several lawsuits. Missouri’s Supreme Court finally ruled in her favor in 1941, ordering the university to admit her because there was no equivalent program at all-Black Lincoln University. Mizzou subsequently closed its graduate program, claiming professors and students were being siphoned away by World War II.

Bluford never took a class at MU, but her fight helped nudge the school toward integration. Mizzou was forced to establish a journalism school for African-American students at Lincoln, and admitted its first Black student in 1950. The university would honor Bluford decades later, the journalism program awarding her its Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism in 1984 and the school conferring an honorary doctorate in the humanities in 1989.

Bluford went on to a 69-year career with The Call, moving from reporter to city editor to managing editor and finally editor, owner, and publisher. She made the weekly newspaper a prominent voice for African-Americans in the city and a force in the fight against discrimination.

The Library named its branch on Prospect Avenue for her in 1988. In 2002, a year before she died at age 91, the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce named her Kansas Citian of the Year.

Read more about Lucile Bluford’s legacy Download a Lucile Bluford biography sheet

Courtesy Missouri Valley Special Collections

The lobby of the Bluford Branch features an exhibit about Lucile Bluford's work in civil rights and journalism.

Members of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority - to which Lucile Bluford once belonged - at the inaugural Lucile Bluford Day celebration in 2017.

ARCHIVED SIGNATURE EVENT

Lucile Bluford: Her National Closeup

July 11, 2018

In this Library program from 2018, Sheila Brooks examined Bluford’s life and pioneering work in a discussion of her book Lucile H. Bluford and the Kansas City Call: Activist Voice for Social Justice, co-authored with Howard University’s Clint C. Wilson II. The Kansas City-born Brooks, a former television reporter, anchor, news director, and documentary producer, recounted Bluford’s fight for admission into the University of Missouri’s graduate journalism program and assessed her dual role as a journalist and advocate for the women’s and civil rights movements.

Listen to Event Audio | Event Details | About the Book

Lucile Bluford Coloring Sheet

Lucile Bluford is among the individuals featured in Coloring Kansas City: Women Who Made History, a coloring book produced by the Library's Missouri Valley Special Collections highlighting notable women from our region's past.

About the coloring book Download the Lucile Bluford coloring sheet

MORE About Lucile Bluford

Digital Court Documents

The Library's historical website The Pendergast Years: Kansas City in the Jazz Age and Great Depression has a digitized collection of documents from the National Archives at Kansas City, Missouri, related to the lawsuits that Lucile Bluford pursued against S.W. Canada, the registrar of the University of Missouri, for repeatedly denying her admission to the university. Browse the scanned documents and read some of the contextual descriptions of the materials online.

View Documents

Confronting Injustice: Lucile Bluford and the Kansas City Call, 1939-1942

The Pendergast Years site also features an original article exploring how Bluford used her role as managing editor of The Call to draw attention to her efforts to enroll in journalism classes in the University of Missouri in pursuit of civil rights for African-Americans. An excerpt:

On February 3, 1939, thousands of subscribers to the Kansas City Call opened the weekly newspaper published by and for African Americans and scanned the front page... they saw a remarkable series of six stories under a banner headline, “M.U. Rejects Woman Student.” Positioned prominently was a first-person account by Lucile Bluford, the 27-year-old African American managing editor of The Call, about her historic actions five days earlier when she tried to enroll in classes of the graduate program in journalism at the racially segregated University of Missouri in Columbia (MU). The headline of Bluford’s report was “Nothing Will Happen When Negro Student Is Admitted to M.U.” In the first paragraph, she reiterated that message: “Those who fear trouble if a Negro student attends the University of Missouri may rest at ease—there will be no trouble, no violence of any kind. That is the one significant thing that my attempt to enroll brought out.” Reassuring African American readers who anticipated hostile reaction to her appearance at MU, she also defied the expectations of some whites with her assertion. Bluford’s second first-person story appeared in the lower right corner of the front page, next to a column, “Why I Applied to Missouri U.” A conventional news story and two other short items about the incident provided more details on the front page. On an inside page of this issue was a seventh story, “Desired to Enter M.U. Long Time.” In an era when reputable newspapers rarely featured first-person stories or reports with bylines, this series was uncommon, but this was an extraordinary event. Trying to persuade readers to support the national campaign for educational equity, Bluford and The Call carried on the tradition of African American women journalists and the black press that had advocated racial rights for decades.

Read the Full Article