KCHistory’s New Cache of Historical Photographs Underscores Work of City’s Landmarks Commission

For more than two decades, the Kansas City Landmarks Commission has donated hundreds of historical images to the Library’s Missouri Valley Special Collections – digital photographs and slides that contribute greatly to the MVSC’s efforts to document the city’s architectural history.

The Library proudly announces the addition of 262 newly digitized photographs showing a variety of historic structures and districts spanning the 1940s through the 1980s, a period of rapid change for the city. Including:

The Campbell-Continental Baking Company Building at 30th and Troost, circa 1945.

11th Street facing east in downtown Kansas City, circa 1950.

The Western Newspaper Union Building from a parking lot along 10th Street, circa 1983.

Intersection of Westport and Broadway, 1947.

So, what is a Landmarks Commission?

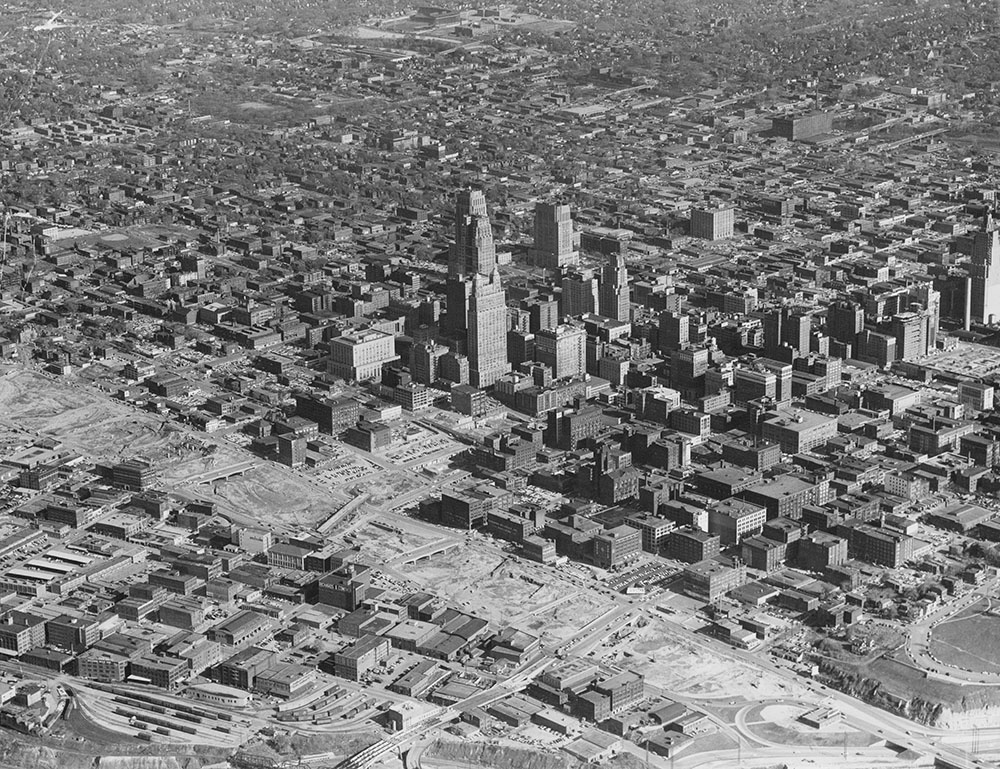

Following World War II, prolonged economic prosperity set American cities on a course of reinvention. An “out with the old, in with the new” mindset ruled the day with modern ideas and architectural designs seen as remedies for urban decay. As city residents increasingly moved out to became suburbanites, demolition equipment moved in to clear a path toward progress. The urban renewal era had arrived.

While urban renewal programs sought to modernize American cities, many began noticing what was being lost as a result. New buildings and expressways meant that older structures fell victim to the wrecking ball. In response, a preservation movement started to gain traction by the mid-1960s.

Passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966 coalesced sentiment, adding the National Register of Historic Places to the existing National Historic Landmarks Program and creating a network of state-level historic preservation offices. Locally, the surge in interest in preserving the past reinvigorated the Jackson County Historical Society, which had been founded in 1909 but had grown dormant until the preservation movement provoked it to action. It spearheaded an impressive list of site renovations, from Jackson County’s 1859 Jail Museum to Missouri Town 1855 and the John Wornall House.

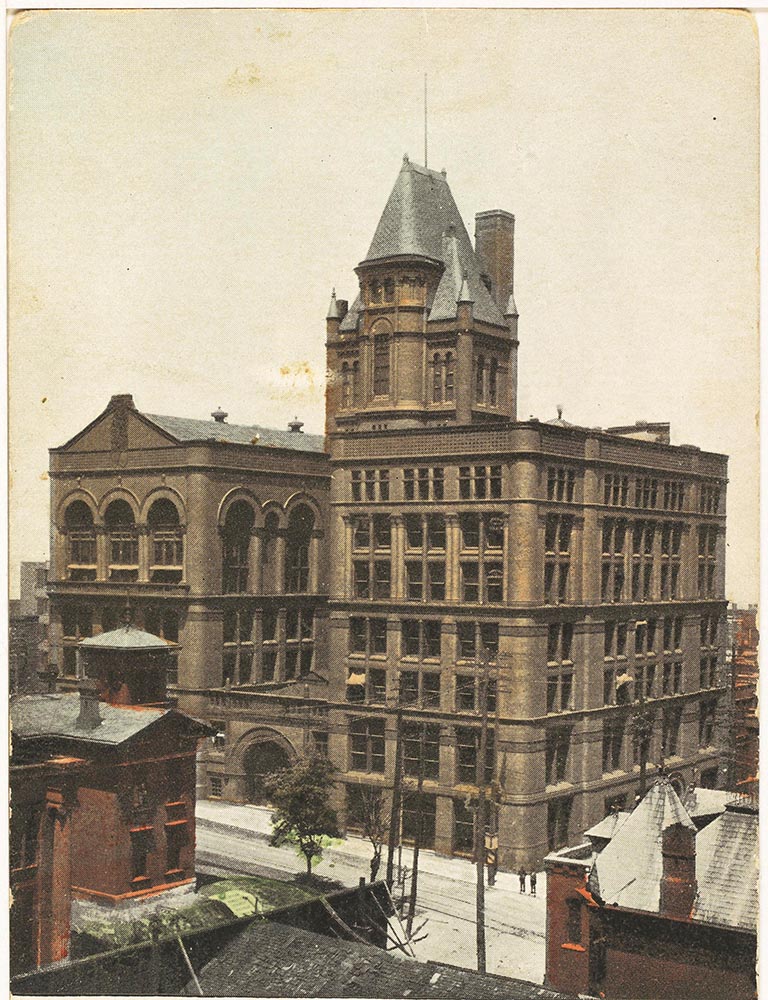

Despite these successes, there were limits to what could be accomplished – as illustrated by the demolition of the Burnham and Root-designed, second Board of Trade Building in 1968. While many spoke out about the prospective architectural loss, there was no organized group to stand in the way of its destruction. The episode drove home the need for a voice on behalf of historic preservation inside City Hall.

The Landmarks Commission was founded in 1970 as a division of the City Plan Commission. It was tasked with taking inventory of Kansas City’s architectural legacy, making historic designations, raising community awareness of preservation needs, and working with funders to restore historic structures and districts. By law, the group consisted of an architect, a historian, an attorney, a mortgage lender, and a realtor. Other appointees had to demonstrate an interest in historic preservation. Mayor Davis named Dr. Kip Robinson as the first chairperson in 1971, with Joseph W. Riedsel, Jacqueline R. Seligson, Mel Solomon, John Edward Hicks, Alfred Renner, and Dr. William M. Ketcham rounding out the seven-person board.

Portrait of Ilus Davis, mayor of Kansas City when the Landmarks Commission was founded, n.d.

The commission’s first big test came in 1971 when a proposed high-rise apartment, office building, and shopping development called for the demolition of Union Station. Rail travel had declined to the extent that only six trains were served by the terminal each day, and so it was seen as expendable. But that didn’t take the structure’s place in Kansas City history into account. Unlike the second Board of Trade building, generations of Kansas Citians had personal connections to Union Station. Public outcry buttressed the behind-the-scenes work of the Landmarks Commission, which succeeded in adding the structure to the National Register of Historic Places and halting any idea of the building’s demise.

The next preservation challenge in 1973, when plans were announced to demolish the Folly Theater to make room for convention center parking – unless someone could meet a $2 million purchase price set by the theater’s out-of-state owners. The Landmarks Commission snapped into action, helping preservation activist Joan Dillon and other Folly advocates found the Standard Redevelopment Corporation and the Performing Arts Foundation to oversee efforts to save the building.

The Folly Theater near the time of its planned demolition, 1970s. Kansas City Public Library.

They were given a 120-day window to get the structure placed on the National Register of Historic Places. The property’s owners then lowered their asking price to $500,000 and, through Dillon’s organizations, fundraising began. The theater ultimately was purchased and renovated in time for a November 1981 reopening.

Over the years, the Landmarks Commission has managed numerous other redevelopment efforts: Westport Square, the Midland Theater, the Scarritt Arcade and the Boley Building to name a few. The commission’s powers were expanded in 1977, and it eventually was rebranded as the Historic Preservation Commission. While the name has changed, its mission has remained largely the same – to advocate for and protect Kansas City’s architectural legacy.

The new additions to the Landmarks Commission Collection can be accessed here.