Why Is There a Large Piece of Ungraded Bedrock on Grand Between Seventh and Eighth Streets?

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Michael Wells

LHistory@KCLibrary.org

"What’s the story?"

“What’s Your KCQ?” — a partnership between The Star and the Kansas City Public Library — is focusing on downtown curiosities this week. Reader Eric Haar got the ball rolling by asking us to explain the odd-looking bit of exposed bedrock that runs along Grand Boulevard between Seventh and Eighth streets. He works in the Western Union Telegraph Building near the site and always notices how much it stands out from its surroundings.

Regulars at the Buffalo Mane Barbershop and Anthony’s Restaurant & Lounge will be well acquainted with the subject as the two businesses directly abut the rocky outcrop.

Anthony’s and Buffalo Mane in front of the rock formation along Grand. Credit: Michael Wells

The crag is conspicuous amid the smoothed-over asphalt environment of downtown Kansas City. And, as with most out-of-place things, there is a story to tell.

To begin, we’ll need to travel back in time – more than 300 million years.

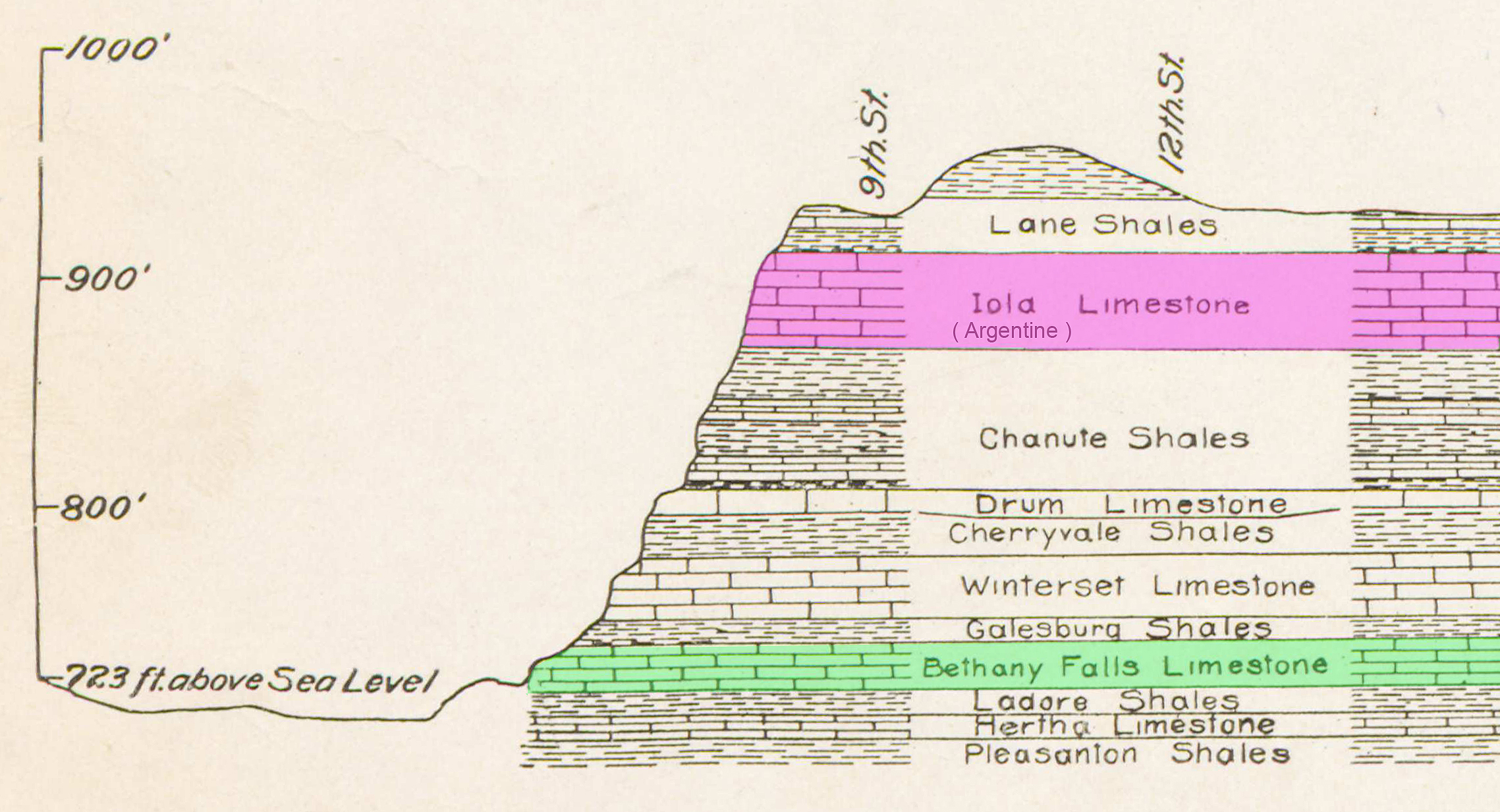

Geologically, Earth was in its Pennsylvanian Age, a prolonged period of rock and mineral formation. What’s now the Kansas City metropolitan area was landlocked within the supercontinent Pangea and covered by a shallow, inland ocean. For millions of years, aquatic organisms lived, died, and deposited their remains on the ocean floor. This organic matter combined with chemicals in the water to form very hard layers of stone – limestone. Occasionally the ocean would recede and leave behind massive deposits of mud and silt, which over time would harden into a less dense rock layer – shale.

As the ocean repeatedly returned and receded, the layers mounted.

rocky formation piquing our reader’s interest is a bit of exposed Argentine Limestone. To better understand it, I reached out to Richard J. Gentile, a professor emeritus of geology at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. In addition to identifying the exact layer, he explained that Argentine Limestone isn’t highly regarded as a source of building material. "The major use was as crushed rock for road surfacing," he said. "Consequently, it was called the 'crusher' ledge by early quarrymen."

Gentile noted that the Argentine layer, once the source of several springs, is visible along Cliff Drive and in areas of Westport. "The springs at Westport are now piped under,” he said, "but they once were the source of fresh water for hundreds of people in covered wagons."

Closeup of Argentine Limestone exposed along Grand Boulevard. Credit: Michael Wells

Providing early residents and travelers with water was not the only way the area’s geology helped grow Kansas City. Long after the Pennsylvanian rock layers had settled and the continents had separated, Earth experienced a series of ice ages. And long after the glaciers had carved out the Missouri River’s path, its confluence with the Kansas River was recognized as an advantageous position for western trade. In 1821, Francois Chouteau arrived from St. Louis and set up a trading post on the north bank of the Missouri near Randolph. However, a flood destroyed the operation in 1826, forcing Chouteau to higher ground on the north bank near today’s Berkley Riverfront Park.

Later, industrious merchant and Westport founder John C. McCoy recognized that a limestone ledge along the river near the foot of present-day Main Street made a natural riverboat landing. Offloading trade goods just a few miles north of Westport would be much cheaper than bringing them overland from Independence. In 1834, a McCoy-led group of Westport merchants supervised the first successful delivery of goods on the ledge and named it Westport Landing.

Unlike the exposed Argentine Limestone along Grand Boulevard, the shelf beneath Westport Landing was Bethany Falls Limestone, a deeper and older layer jutting out along the river near the foot of Delaware Street. The Argentine layer would take on importance as the city expanded south.

By 1850, McCoy and a group of investors had overseen the incorporation of the Town of Kansas. Where the local geology once was advantageous, city leaders now faced the Herculean task of carving a city from the rocky bluffs. Nearly all businesses were situated along the riverfront and reachable only by a narrow road described as barely wide enough for a single cart to pass – the river on one side and towering bluffs on the other. A few paths leading south had been established, but challenges remained. As soon as a bluff yielded, a deep valley would stand in the way. Land would need to be leveled and streets graded if Kansas City wanted to break free from the riverfront.

Cross section of the alternating limestone and shale rock layers beneath Kansas City. UMKC geologist Richard J. Gentile pointed out that Iola was an older name for what is now commonly called the Argentine Limestone (highlighted in pink). The Bethany Falls Limestone that provided the natural steamboat landing utilized by John C. McCoy and other Westport merchants is highlighted in green. 1917. Kansas City Public Library

When Father Bernard Donnelly was assigned as Kansas City’s first Roman Catholic priest in 1846, the savvy clergyman saw a dual opportunity: He could grow his flock while helping to satisfy the massive amount of physical labor needed to smooth the terrain. Donnelly began encouraging America’s newly arrived Irish immigrants to head west where the work was plentiful. His case for Kansas City was made in eastern newspapers popular in Irish communities and in his written correspondence with fellow priests back on the Emerald Isle. Donnelly even covered travel expenses for 300 men to travel to Kansas City, with two caveats: They had to be from the Irish province of Connaught to promote unity, and in very un-Kansas City-like fashion, they had to stay away from liquor.

The first arrivals filled boarding houses and shacks along Sixth Street between Broadway and the bluffs overlooking the West Bottoms, earning the area the nickname of Connaught Town. From this base, droves of workers began the grading work. Carving paths through the bluffs was one thing, but between five and 50 feet of loess – or windblown silt from the river bottoms that had settled atop the bluffs – often had to be hauled away before the rock excavation could begin. In his history of Kansas City, Theodore S. Case observed, “If a hill was in the way, they cut it down. If a ravine interfered, they threw the hill into it.”

The work of grading the streets continued for decades. Around 1870, excavation began in the Grand Boulevard area where our reader noticed the limestone projection. As development advanced southward, many of the downtown buildings that make up today’s Kansas City skyline were anchored to the underlying layer of Argentine Limestone.

Grand Boulevard facing south, with Argentine Limestone and loess accumulation still visible. A White Castle hamburger restaurant occupies what’s now the Buffalo Mane building, 1926. Kansas City Public Library

It is uncertain why the exposed bedrock in question was not graded, though several residences and other structures remained atop the escarpment through at least the 1950s and it’s likely that the owners were in no hurry to see their properties razed. While the buildings eventually were cleared, we are left with a bit of Argentine Limestone as a reminder of our geological past, of the natural advantages that helped give rise to a city, and of the hard work and determination of one of Kansas City’s first immigrant communities.

How We Found It

Richard J. Gentile’s Rocks and Fossils of the Central United States with Special Emphasis on the Greater Kansas City Area is an invaluable recourse for understanding Kansas City’s geological past. Theodore S. Case’s History of Kansas City, Missouri provided details related to the establishment of Westport Landing and early Kansas City. Lastly, Pat O’Neill’s From the Bottom Up: The Story of the Irish in Kansas City filled in details about the contribution of Irish immigrants to the city’s street grading project and expansion southward.