KC Q Explores the Town of Kansas Bridge Structures

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

Riverfront Ruins

Maybe you’ve noticed the old concrete structures near the Town of Kansas Bridge in Berkley Riverfront Park. Both Kyle Romine and Joel Verhagen have, and separately raised the question to What’s Your KC Q: How were they once used?

Richard L. Berkley Riverfront Park, named for the longtime Kansas City mayor, offers Kansas Citians a unique opportunity to reconnect with the Missouri River in a variety of ways – from strolling among cottonwoods on the Riverfront Heritage Trail to visiting a 1.5 acre wetland restoration project, getting in a game of sand volleyball, or even joining a pop-up fitness class. The list goes on.

While Kansas Citians of the past had a vastly different relationship with the Big Muddy than we do today, those ties run deep and hearken back to the city’s very beginning. In fact, it is possible to find bits of the limestone ledge once called Westport Landing peeking out along the steep riverbank. Much of the ledge is now covered with soil, but it was here that traders like John McCoy brought in trade goods to keep their Westport store shelves stocked. As the area’s trade focus shifted away from overland trails and toward railroads and cattle, the landing was renamed Kansas City and rapidly outgrew the town of Westport to the south.

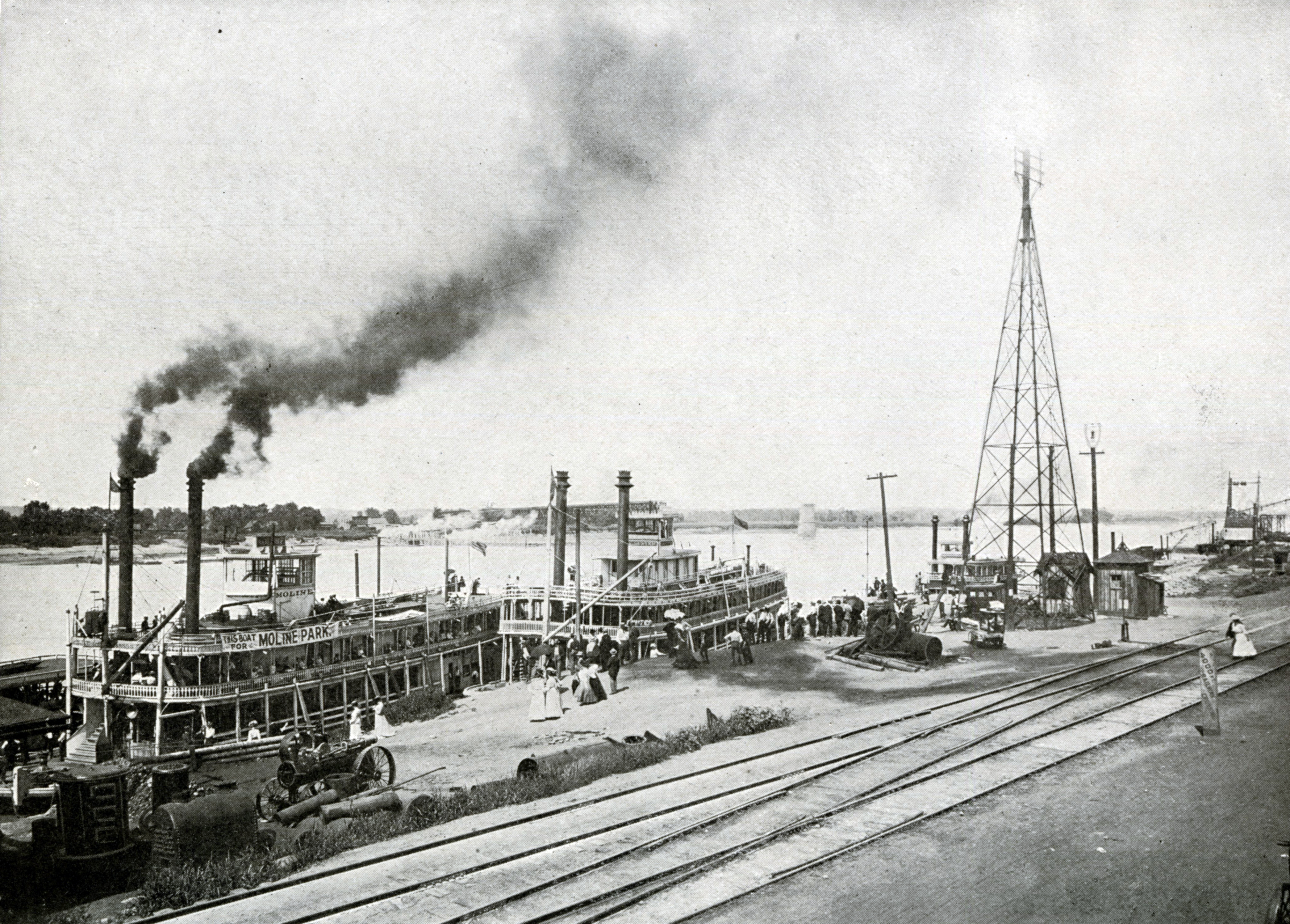

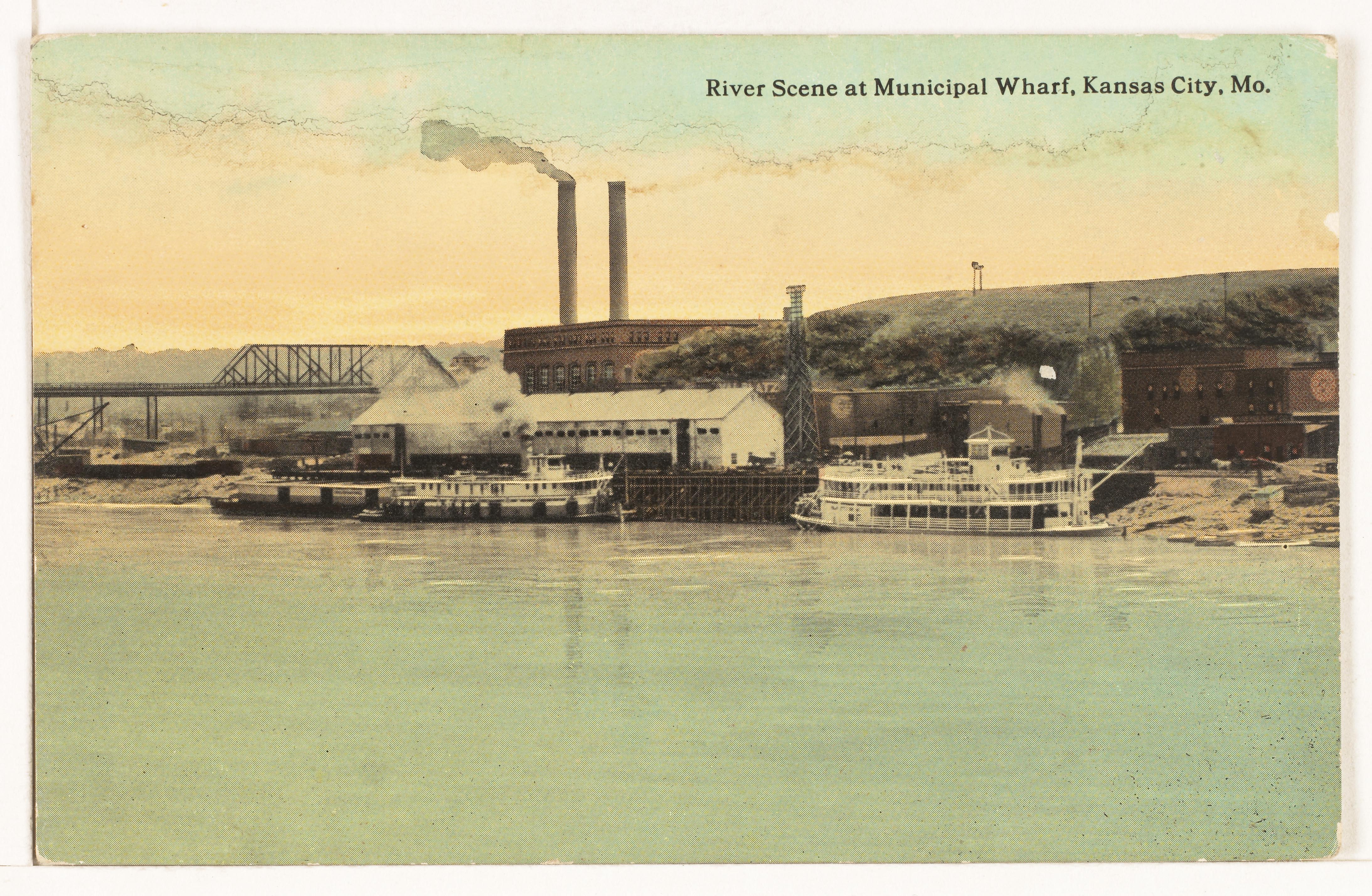

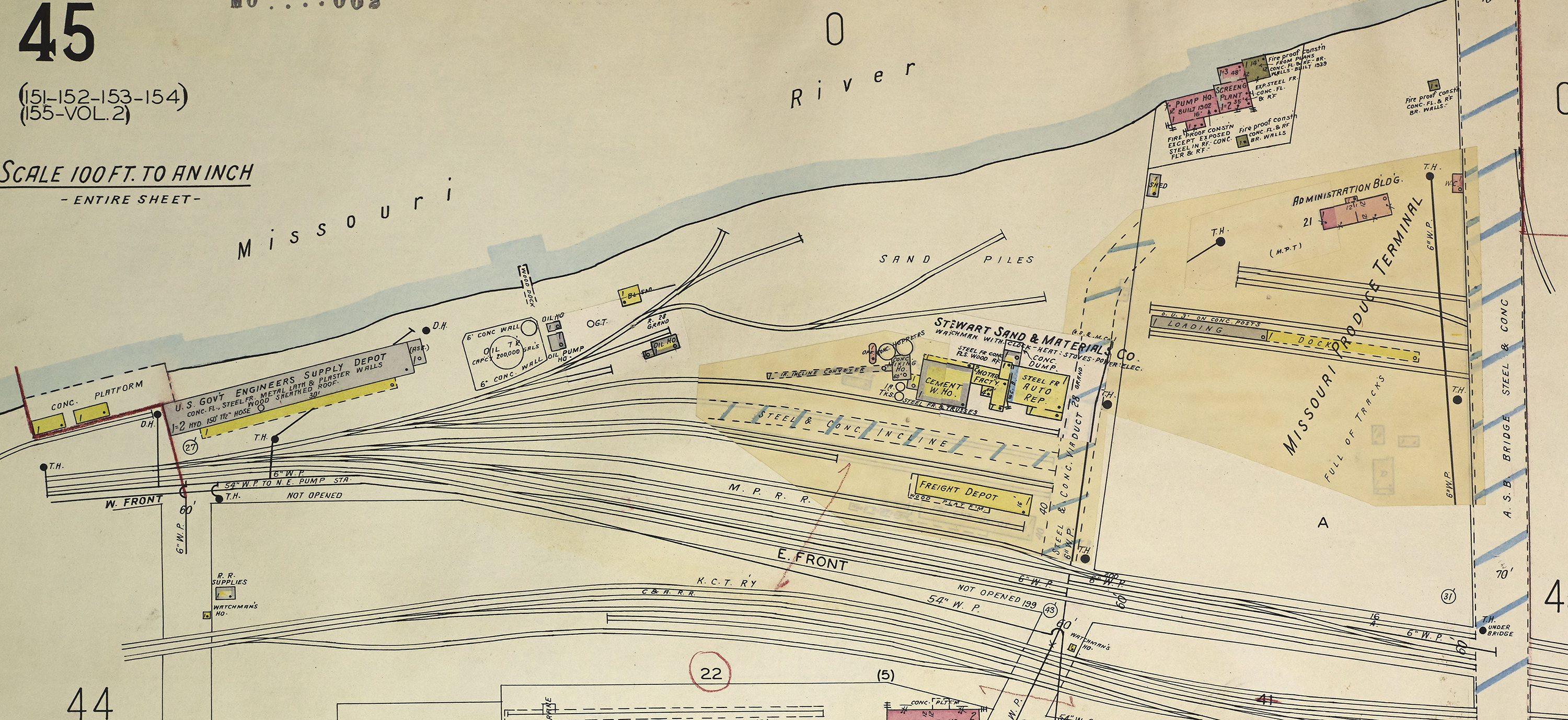

This is where the strange concrete structures we see today come into the picture. Despite the economic boom going on in Kansas City, the old limestone ledge in use since the 1850s was still the best way to load and offload riverboats in the early 20th century. In 1911 the city finally got around to constructing a municipal wharf at the foot of Main Street. Plans called for a wooden dock with an accompanying warehouse measuring 300 feet by 40 feet. The ground was leveled between the warehouse and city streets to the south to allow wagons to transport freight to and from the wharf.

By 1918, the municipal wharf had a new neighbor to the east, the Stewart Sand and Material Company. It dredged the Missouri River for sand and gravel, which was stored in gargantuan piles that drastically altered the character of the riverbank until the company ceased operations in the early 1980s.

After a fire claimed the wharf’s wooden dock in 1928, city leaders began making plans for more modern facility. Eventually a site was selected in the West Bottoms at the Missouri-Kansas border. The new wharf opened in 1931, and the remains of the old Main Street wharf were left vacant.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers moved in shortly thereafter, using the buildings for flood control and Missouri River navigation projects. At some point prior to 1939, the circular concrete platform immediately east of the old warehouse was constructed to support a 200,000-gallon oil silo. It is uncertain when the silo was removed, but we know that the Corps of Engineers vacated the site in 1992. The warehouse building was demolished, leaving the long rectangular foundation that sits east of the bridge today.

The sand and gravel business continued to thrive well into the mid-20th century, so the land between the Hannibal and ASB bridges remained in use. East of the ASB Bridge was a different story. In 1954, the city purchased the property for $400,000 to develop as a future baseball stadium site. However, the idea stagnated, and the area remained empty. By the mid-1960s, sites in the Central Business District and an area east of downtown adjacent to the Blue River known as Leeds were given preference for future stadium construction. Bids for the unoccupied stretch of riverfront were pitched to the city by various developers over the years, but a suitable buyer could not be found. It was thought by some that the land could be used for a state-of-the-art exhibition center, but the riverfront tract lost out to a strip of downtown real estate occupied by today’s Bartle Hall.

The area east of the ASB Bridge subsequently fell into serious decline, a portion even used as a dumpsite for demolition waste. It’s where the rubble was hauled after Kemper Arena’s roof collapsed in 1979. Help came in the mid-1990s when Missouri voters amended the state’s constitution to allow riverboat casino gambling. In 1993, The Hilton Hotels Corporation struck a deal with the Kansas City Port Authority allowing it to construct a casino east of the Paseo Bridge (the Isle of Capri) – in part in exchange funds to construct a new riverfront park.

The park opened in October 1998 but was very much a work in progress. At that time, park boosters and officials from the Port Authority hoped it would inspire new interest and investment in the long-neglected riverfront. But soil contamination by an energy firm once occupying the land would have to be resolved before any development could take place. After lengthy litigation, Missouri Gas Energy settled with the Port Authority and agreed to a $3.4 million environmental cleanup.

Then came another complication: opposition from downtown real estate interests. Leaders with the Greater Downtown Development Authority believed that any riverfront development would derail renewal closer to the heart of downtown. Their concern in the early 2000s was not unfounded; the Port Authority had made unsuccessful overtures to Sprint and the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, and had designs on building a largescale office park. Riverfront supporters, meanwhile, espoused the believe that riverfront development should go hand in hand with downtown redevelopment.

The park remained a bit of an anomaly due to the false starts. Flush with amenities, it seemed to lack what successful parks need most: regular visitors. As recently as a few years ago, it was common to feel alone in the park on a Sunday evening stroll. The park’s coffee bar style seating offering impressive an impressive view of the river often sat empty with the nearest café’, in the River Market, nearly a mile away by foot.

Recent visitors will notice big changes. A rotating slate of family- and fitness-oriented activities is drawing new people to the park. The annual KC Riverfest offers the most spectacular Fourth of July fireworks viewing in the metro area. And redevelopment is finally happening. The 410-unit Union Berkley Riverfront apartment complex, which opened in the spring of 2018, brought new downtown residents to the river’s edge for the first time in decades. Later that summer, Bar K Dog Bar opened its doors. There, canine visitors can take advantage of a two-acre, off-leash dog park while their human companions enjoy a restaurant and bar constructed entirely of repurposed shipping containers, a throwback to the area’s history as an industrial and shipping hub.

Officials with Port KC and the Kansas City Streetcar Authority hope to extend the downtown streetcar line to Berkley Riverfront Park via the Grand Avenue Viaduct – something that will require buy-in from the Isle of Capri casino’s current operator Twin River Worldwide Holdings. As always, only time and the passing of the river current will reveal what’s in store.