KC Black History: Do you know the story of the first and last all-Black town in the West?

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Kynala Phillips | Kansas City Star

Editor’s note: This story is part of our Black History Month KCQ series and was fueled by questions from students in Kansas City area Black Student Unions. Students at Washington High School in KCK and Olathe South High School asked to learn more about the legacy of Black land ownership and Black farming in Kansas, and specifically about the all-Black town of Nicodemus.

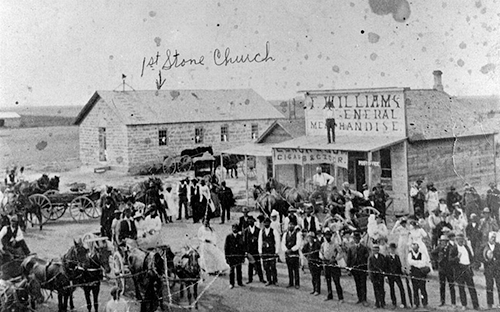

west of the Mississippi River. At one time, in the late 1800’s, more than 600 people

called the farm community home. | Travis Heying, The Wichita Eagle

When Veryl Switzer was a child growing up in the 1940s in Nicodemus, Kansas, there wasn’t a whole lot of play time, according to his daughter Teresa Switzer.

“You're in the farming community, you do your chores and you do your schoolwork—which my grandmother was a very big proponent of—and then you go to bed early,” Teresa Switzer said of her father’s childhood in the all-Black settlement in Graham County.

Ora T. Wellington-Switzer, Veryl Switzer’s mother, would take her family to church each Sunday. After service, kids would play while the adults would catch up with each other. Wellington-Switzer would sell meals on Sunday too.

“It was a simple life, but it was a really fulfilling life,” Teresa Switzer said of Nicodemus, the oldest Black town west of the Mississippi.

In Nicodemus, people owned land and ran businesses, offering a level of agency many had never experienced before.

“That was the crux of why they wanted to come and homestead in northwestern Kansas, where they could govern themselves, have their own educational systems, their own government and also have their own source of income,” said Dr. JohnElla Holmes, who is a fifth generation descendant of Nicodemus settlers and president of the Kansas Black Farmers Association.

“That's one of the reasons that Nicodemus even came to be, was to help them have their own freedom.”

A legacy worth preserving

Like Holmes, the Switzer family are descendants of the first pioneers to call Nicodemus home—people like Zachary and Jenny Fletcher.

The Fletchers were two of the first entrepreneurs in Nicodemus after the town was established in 1877.

Zachary Fletcher built the St. Francis Hotel in 1881. His wife Jenny became a postmistress, school teacher and a hairdresser. All of their endeavors were housed in that hotel building, which became a focal point of the community, according to the Nicodemus Historical Society.

Nearly 52 years later, Veryl Switzer and his siblings were born in that same building. After graduating high school, Switzer became the first African American football player to earn a scholarship to Kansas State University and one of the first to integrate the NFL’s Green Bay Packers. As his stardom grew, he remained committed to his home of Nicodemus.

“Veryl Switzer is one of our greats,” said Holmes. “He had the wisdom to say, our history needs to be preserved, and these buildings need to be preserved.”

Veryl Switzer, now 89 years old, owns the two-story stuccoed building where his ancestors ran the St. Francis Hotel, which is just one of five historical structures left in town.

With just 20 residents left today, Nicodemus is both the first and also the last remaining all Black town in the west, according to Angela Bates, who is a town descendent and the founder of the Nicodemus Historical Society.

So how did this all-Black town even come to be?

Newly free Black folks started to migrate out of the south after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act in 1862 and emancipated the enslaved in 1863.

The Homestead Act made it possible for folks to take their newfound freedom out west by encouraging people to buy and cultivate federally owned land.

This westward migration dubbed The Great Exodus became prominent in 1879, around 30 years before the Great Migration north, and two years after the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of Jim Crow. The Black migrants were called exodusters.

The story of Nicodemus starts a couple years before the Great Exodus, but the success of the town was still fueled by this mass migration.

Nicodemus was founded by Rev. W.H. Smith, a Black minister and homesteader in the area, and a white land promoter named W.R. Hill. Land promoters played a key part in the planning, marketing and overall development of a town.

The pair worked with five Black ministers to create the Nicodemus Township Company, which allowed the town to become an all Black town for profit.

They picked the name Nicodemus because of the biblical figure, a Jewish ruler who publicly defended Jesus.

“They say he was wise,” Bates said. “And there was a song that was sung in the plantations about him. That song basically said ‘Wake Nicodemus up for the great Jubilee,’ which meant freedom.”

“So, I think that’s why they named the town Nicodemus,” she said.

Who moved to Nicodemus, and why?

In the spring of 1877, the founders set out to recruit Black folks throughout Kentucky and in some parts of Tennessee and Mississippi to come to Nicodemus.

Families paid a fee of $5 for transportation out to Kansas and membership in the town’s colony.

“The bulk of the people that were solicited came from the Central Bluegrass Area, the Lexington and Georgetown area of Kentucky,” Bates of the Nicodemus Historical Society said. “They went to the churches there and recruited the people. They said, `We'll be back to get you all that are interested.’”

Later that fall, Black migrants boarded local trains headed north to Cincinnati, where they would board a train out west to the city of Ellis, Kansas. Once they arrived, they endured a two-day walk to Nicodemus.

The chance to escape racial violence and Jim Crow laws, govern themselves and own their own land was irresistible to many newly freed Black people. That hunger for agency led to a number of all-Black settlements in the Great Plains. Nicodemus was the first all-Black town in Kansas, but soon more than a dozen Black colonies popped up.

At its peak, Nicodemus was home to more than 600 residents.

A thriving Black township

The migrants had skills growing crops like hemp, tobacco and wheat, so one of the main attractions to Nicodemus was the land, according to Bates. Families lived off of their gardens, chickens, pigs and cows and made income by growing wheat.

“We are proud to say it is the finest country we ever saw,” said Rev. Simon Roundtree, one of the founders, in an 1877 ad to “the colored citizens of the United States.”

“The country is rather rolling, and looks most pleasing to the human eye…with plenty of provisions for the colony,” he wrote.

While selling land for homes, the founders were also adamant about selling business lots on the town’s main street.

Within 10 years of being established, the town had blossomed into a thriving Black-owned business hub. There was a doctor’s office, a drug store, multiple land companies, multiple banks and hotels, general stores, livery stables and much more, according to Bates.

Why would people ever leave Nicodemus?

“The only reason that we didn't become [a more bustling city] and just prosper more and keep growing, was the fact that the railroads did not come through,” said Holmes from the Kansas Black Farmers Association.

Holmes said that in 1887, her great great grandparents worked with other townspeople to raise $16,000 in bonds and even dedicated land for a railroad to attract the Missouri Pacific Railroad to Nicodemus.

The Missouri Pacific Railroad ultimately withdrew its plan to build a railroad through Nicodemus, while the Union Pacific Railroad constructed a route just four miles southwest in a town that would become known as Bouge.

“Then as a result, that town, once it was created, lured some of the businesses out of Nicodemus, such as the bank, and Nicodemus lost its economic base,” Bates said. “Then from that point onward, Nicodemus has went into a kind of downward spiral.”

By the 1930s, the Great Depression and extreme drought in the plains, known as the Dust Bowl, brought more challenges to Nicodemus. Soon residents began to migrate further west to larger cities.

“The population has continued to dwindle. It's down to just about 20 people now,” said Bates, adding that her parents migrated out of Nicodemus in the 1950s after she was born.

Homecoming and history

Although the original land developers and settlers might not have foreseen the eventual downturn of the township, they were determined to make sure their legacy was preserved and celebrated.

In 1878, after settling in, the townspeople started their first Emancipation Celebration, which evolved from an event celebrated on Aug. 1 called the Colored People’s fairs in Kentucky, according to Holmes.

“Nicodemus has gone down into the history books, and part of that is because they knew that they needed to do something to sustain it,” Holmes said.

Jan. 20, 2009 at the township hall Nicodemus, Kansas. | Charlie Riedel, Associated Press

This year Nicodemus will be celebrating its 144th Annual Emancipation Day Celebration, also known simply as Homecoming. Each year, descendants of Nicodemus settlers flock back to town on the last weekend of July to reflect on their history and lineage.

Throughout Bates’ childhood in California, her parents made it a point to come back each summer for the Emancipation Celebration. She said her trips to Nicodemus as a child motivated her to keep learning about her home.

Bates finally moved back to Nicodemus in 1989, after establishing the historical society. She started collecting photographs, books and magazines, and she interviewed residents and other descendants.

“In 1992, I wrote to Senator [Bob] Dole and asked him if he would consider making Nicodemus a part of the National Park Service to help us to preserve and protect this chapter in American history,” Bates said.

By 1996, President Clinton signed the legislation that allowed for the town to become a unit in the National Park Service.

“We wanted to make sure that our faces and our stories were going to be remembered,” she said. “For years to come Nicodemus will always be remembered as a part of this history as it relates to the migration in the settlement in the West.”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.