All Library locations will be closed Monday, January 19 for Martin Luther King, Jr. Birthday.

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

by Dan Kelly | dkelly@kcstar.com

At one time, this Kansas City entertainment complex had a 14,000-square-foot dance floor, a pool, ice skating and roller skating rinks. But then came rock ‘n’ roll.

As world events fractured into World War II, young Teresa Peck found solace at the Pla-Mor.

First, she glided around the vast entertainment complex’s ice skating rink, then in warm weather she enjoyed the swimming pool. Later came visits to the bowling alley. Eventually, she frequented the giant ballroom.

“It was unique,” Peck said. “I guess I was sentimental about it, and that’s why I wrote it in.”

Peck is far from alone in having fond memories of the Pla-Mor, which was Kansas City’s place to find entertainment and romance for more than three decades — if you were white. And she wasn’t alone in submitting a Pla-Mor question to “What’s Your KCQ?”, The Star’s ongoing series with the Kansas City Public Library that answers readers’ queries about our region. At least two other readers have mentioned the place in recent KCQ submissions.

Her query said, in part:

“I would like to know the background of that marvelous play center named the Pla-Mor. … Someone must have read the minds of Kansas City citizens when they brought us all that fun.”

Situated at Main Street and 31st Terrace, near the center of the city at the time, the Pla-Mor opened in 1927, survived the Depression, thrived during World War II but was doomed by TV and rock ’n’ roll. The main building was repurposed first in the 1950s as a huge bowling operation, then in 1970 as a rock concert hall (an effort that did not go well) before being demolished in 1972.

the center of the city at the time, opened in 1927. | Kansas City Public Library

Kansas City’s ‘first pretentious ballroom’

When real estate and construction mogul Paul Fogel purchased the building that had housed the Stop and Shop Market in 1925, he had no idea what to do with it. Then it came to him: Turn the big white building into a giant amusement center, with an elegant ballroom at its core that would put Kansas City in a league with New York, Detroit and Chicago at the height of the Jazz Age.

He would call it the Pla-Mor, combining — according to one report — the names of his children, Paulene and Morris.

On Nov. 19, 1927, The Kansas City Times reported that “Kansas City’s first pretentious ballroom” would open at 3142 Main St. a week later on Thanksgiving night. It was Pla-Mor’s second phase, bowling lanes having opened in September. The Pla-Mor Ice Palace, with a seating capacity of 6,300, was scheduled to open by Christmas.

Opening night at the Pla-Mor Ballroom attracted 4,100 people who were dazzled by a 14,000-square-foot dance floor supported by 7,800 comfort-inducing springs, with two massive chandeliers that changed colors looming overhead and elegant touches such as velour tapestries, plush carpet, tinted lamps and Italian furniture throughout the building. The Jean Goldkette Orchestra played.

What was billed as the nation’s largest indoor entertainment center was designed by architect Charles A. Smith, who was known for his work on Kansas City’s public schools, and was built at a cost of more than $500,000.

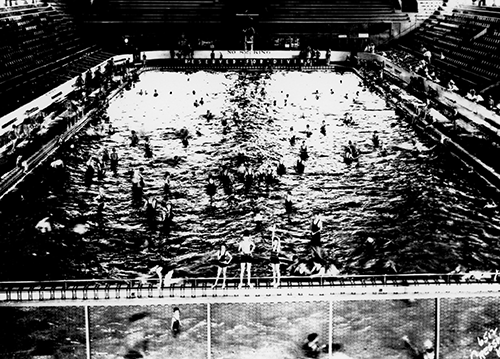

By the time Teresa Peck was old enough to visit the Pla-Mor about a decade later, a roller rink had been added next door. Also, a 190-by-70-foot swimming pool, described as the largest west of the Mississippi, was constructed under the ice rink so that the facility could be used year-round. In the summer, sand beaches invaded the parking areas.

so that area could be used year-round. | Goin’ to Kansas City Collection courtesy of the Kansas City Museum

Billiards and pool were available in the main building, as were a barber shop, beauty shop and café. The complex at one time or another would play host to wrestling, basketball, car racing, softball and baseball.

“When I say it was an entertainment center, it truly was,” Peck said. “It was amazing to have an ice rink, a swimming pool, a bowling alley and a dance floor.”

She said she went ice skating, roller skating and/or bowling every week. In the summer, she was at the Pla-Mor daily because she worked at the swimming pool.

Getting there from her home off Swope Parkway was no problem.

“The streetcars in that era were really good,” she said. “That was simple.”

The Pla-Mors of the American Hockey Association became Kansas City’s first professional hockey team, and the Ice Capades visited annually.

Betty Kostelac taught ice skating and roller skating at the Pla-Mor and was so accomplished she earned an invitation to join the Ice Capades. Instead, she remained a regular at the Pla-Mor, becoming an accomplished ballroom dancer and participating in water shows.

According to a 2011 tribute in The Star after her death at the age of 86, Kostelac performed a dive from the rafters with her cape on fire, splashing 40 feet down into the pool with kerosene floating on the water. “In the stunt’s grand finale, a flash of fire exploded as she broke the surface,” the article said. “Apparently, her mother knew nothing of the feat until Betty came home with singed eyebrows.”

Big stars and segregation

For most of its history, the ballroom was Pla-Mor’s centerpiece.

Why not? The most famous big band and jazz performers of the time played there, including Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton, Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, Harry James, Woody Herman, Guy Lombardo, Stan Kenton and Ella Fitzgerald. Oh, and Frank Sinatra.

“They had a huge dance floor and first-name bands back then,” Peck said. “I remember going to dances, oh, in the late 1940s and the 1950s. It was extremely popular. It was always crowded.”

Hoagy Carmichael, who became one of the 20th century’s premier composers with songs such as “Georgia on My Mind” and “Heart and Soul,” played piano for the house band in the late 1920s. It was at the Pla-Mor that he introduced his most famous composition, “Stardust,” to the dancing public.

“I remember after the band played it, a couple asked me the name of it and who wrote it,” he later told The Star. “I told them it was just a tune I wrote. They were very flattering about the song. That must have been the first time it was danced to.”

A young bandleader from North Dakota brought his orchestra to the Pla-Mor in 1932 for a battle of the bands. Lawrence Welk returned several times over the next 20 years, including once when he broadcast his coast-to-coast program from there live on ABC radio.

hitting the big time with his long-running television show. | File Photo

Soon thereafter, Welk moved to television, where the “Lawrence Welk Show” was a mainstay for three decades.

When he brought his “champagne music” orchestra for a show at Municipal Auditorium in 1970, he reminisced a bit.

“I used to play Kansas City in the old days … at the Pla-Mor ballroom,” he told The Star. “In those days, I was leading a territory band out of Yankton (South Dakota), and we weren’t known there. I used to want to play at the Muehlebach, but they would never hire me.

“I’m still halfway mad at them.”

Welk was joking about being angry at the Muehlebach Hotel. Cab Calloway had legitimate reasons to hold a grudge against the Pla-Mor.

An incident there on Dec. 23, 1945, put the ballroom and Kansas City in headlines around the country — and they weren’t flattering.

Pla-Mor Ballroom in 1945 and got hit with a pistol for his troubles, an incident that earned

the Pla-Mor and Kansas City negative publicity. | File Photo

Calloway, a famous jazz musician and bandleader, went to the Pla-Mor at the invitation of fellow Black bandleader Hampton, who was playing a dance concert. When Calloway and a friend bought tickets and tried to enter the whites-only club through the front door, they were rebuffed.

The incident escalated to the point that an off-duty police officer named William Todd, who was working security, whacked Calloway on the head with his pistol. When Hampton learned of the incident, he refused to continue playing, and he never appeared at the Pla-Mor again.

Calloway wound up in the hospital with eight stitches — and he, not Todd, faced three misdemeanor charges.

In a packed Municipal Court hearing room a few days later, Judge Earl Frost dismissed the charges. “As I listened to the case, I felt that Calloway had been very badly mistreated,” Frost said nearly 50 years later.

Calloway sued the Pla-Mor for $200,000; the Pla-Mor counter-sued for $100,000. After a three-day trial in 1947, the jury awarded damages to neither side. The Missouri Supreme Court later ruled that Calloway was entitled to a new trial, but he didn’t pursue it.

When he returned to Kansas City in 1964 to star in “Porgy and Bess” at the Starlight Theatre, Calloway showed off the scar on his skull. But he wasn’t bitter.

“I think that if it had been tried today, civil rights where they are, I would have won,” he said.

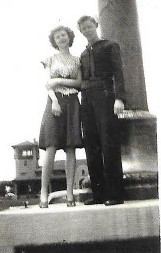

spent a night roller skating at the Pla-Mor. | Courtesy of Teresa Peck

War and romance

The Star’s obituaries over the past 15 years have been dotted with variations on a theme:

- Lucile C. Carlisle (Enyeart) met her future husband, Charley, at the Pla-Mor ice skating rink.

- Emmett Stephenson’s love of music and dance led him to meet Maurine Helm at the Pla-Mor Ballroom. They married in 1941.

- Lucian Piane met his wife, Lucille, in 1944 while dancing at the Pla-Mor. They were married on Oct. 10, 1945.

- Vivian Kropf Mathews’ life changed in 1949 when she met the love of her life, Bob Mathews, at the Pla-Mor Ice Rink.

- Betty met Bill Lafferty while dancing at the Pla-Mor Ballroom, and they married in 1949.

- In 1945 at the Pla-Mor Ballroom, Josephine met Bob Elmer, who had served in the Merchant Marine. They danced, became engaged one week later and married in 1946.

Longtime Pla-Mor manager Will Wittig estimated that 75% of the dancers came as stags during World War II, and many of them found romance.

“I don’t know how many times married couples came up to me and said, ‘This is where we met,’” Wittig told The Star in 1957.

The USO, where soldiers could find recreation and other services, was nearby, and both it and the Pla-Mor were hot spots during World War II. That was when the Pla-Mor reached the height of its popularity, with the likes of Kenton and James drawing crowds of more than 4,000.

Not all the memories were made on the dance floor, however, and not all wound up in romance.

Jane Jones Aubrey wrote in “Pla-Mor Memories” for The Star in 1995:

“One night my friend’s boy cousin from Boston was down for the weekend. After bowling we walked my friend home first, and then he walked me home. He was very polite. I remember feeling grown-up for the first time. I was 16. He was old —18 — and soon to be a Navy man fighting for our country.”

Teresa Peck didn’t meet her spouse at the Pla-Mor, but almost.

“I was with my girlfriend, and we had gone roller skating at the Pla-Mor,” she said. “And to get a streetcar, we had to walk past the USO, and that’s how I met my husband. He came out and said hello, and we got on the streetcar.

“And we ended up going on our first date the next day, which was Easter Sunday, and we went to the Cathedral downtown on our first date.”

Teresa and Don Peck, who was in the Navy, were married 2 1/2 years later in 1947. They will celebrate their 74th anniversary on Nov. 29.

Bowling balls, rock stars and new cars

After World War II, Pla-Mor’s popularity gradually declined. Not even booze could save it.

No liquor was sold at the Pla-Mor (although 3.2% beer was permitted after a while). Of course, that doesn’t mean the ballroom was alcohol-free. You can be certain that flasks and other containers made their way onto the dance floor.

Alcohol sales finally were introduced in the ballroom’s waning days, but in vain. The final public dance on June 14, 1957, featured Les Harding and Orchestra.

At the time, the demise of ballrooms all over the country was blamed on the growth of television and smaller clubs … and rock ’n’ roll.

Waldo Favreau, manager of the Pla-Mor when it closed, said, “There used to be more romance to dancing. Rock ’n’ roll is mass hysteria. They look like they’re going nuts out there. It’s scaring away the timid and nicer kids.”

Perhaps some of those “nicer” kids stuck around when the building was converted into a massive bowling operation with 54 lanes. It operated until 1966, then remained vacant for several years until going over to the dark side — rock ’n’ roll.

Renamed Freedom Palace, the maple floor where Armstrong, James, Herman and Kenton once performed now featured the likes of Canned Heat (who opened the venue on May 8, 1970), Grand Funk Railroad and Quicksilver Messenger Service.

The highlight — as well as the lowlight — came when the British mega-band The Who appeared on July 2, 1970. Alas, the high temperature that day was 101 degrees, and it was still 99 at 7 p.m. when 3,500 bodies crammed together in the “Palace,” where air conditioning either didn’t exist or was overwhelmed by circumstances.

“It had all the comforts of jungle survival training in Panama,” The Star’s story the next day began.

The band began playing at 9:30 p.m., an hour-and-a-half late, and soon thereafter Pete Townshend’s amplification system cut out, the first of several similar problems. The sound system failed during “I’m Free.” All in all, it was a technical nightmare in a sweat-filled cauldron.

So perhaps it was no surprise that Freedom Palace survived less than seven months.

In 1972, founder Paul Fogel’s son decided to raze the building to make the property more marketable, and a Cadillac dealership eventually was built.

Nearly 50 years later, the site still houses a car dealership, and the echoes of The Who as well as of Welk, Calloway, Hampton and Sinatra, have long since fallen quiet. But memories continue to dance in the minds of many Kansas Citians.

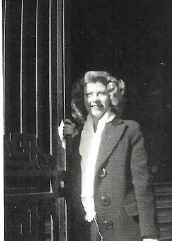

submit a question to KCQ about the history of the place. | Courtesy of Teresa Peck

“I honestly can’t imagine my entertainment life from the time I was young until past teenage if it wasn’t for the Pla-Mor,” Teresa Peck said.

She figures her adult life also would have been totally different without the place.

“If we hadn’t gone to the Pla-Mor roller skating that night, I would have never met my husband,” she said. “It is kind of interesting — I didn’t think about it before — but we just happened to go roller skating that night.”

That decision remains a happy one three-quarters of a century later.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.