Black Bob is all over this part of Johnson County. Here’s the tragedy behind the name

“What’s your KC Q” is a joint project of the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Readers submit questions, the public votes on which questions to answer, and our team of librarians and reporters dig deep to uncover the answers.

Have a question you want to ask? Submit it now »

By Dan Kelly | dkelly@kcstar.com

Out-of-towners might be a bit shocked when they drive through Olathe, the county seat of Johnson County.

If the name of Black Bob Road doesn’t grab their attention — and perhaps raise their eyebrows — then Black Bob Elementary School, Black Bob Park, Black Bob Bay water park, Blackbob Marketplace, Black Bob Court Townhomes, Blackbob Pet Hospital or Blackbob Park Batting Cages & Mini Golf might.

Olathe is, without question, the Black Bob capital of the world.

So, is that a bad thing?

Thomas Greaves wondered just that in his query to “What’s Your KCQ?,” The Star’s ongoing series with the Kansas City Public Library that answers readers’ questions about our region:

Who is Black Bob Road in Olathe named for, and is there any reason it should be renamed?

Given the current climate of sensitivity toward traditional names of places, things and team mascots, his is a timely question. Johnson County itself is wrestling with the possibility of renaming Negro Creek, which flows through Leawood’s Ironhorse Golf Club.

“I’m sure that question comes up often,” Tim Danneberg, Olathe’s director of communication and customer services, said of public inquiries about the name’s appropriateness.

Its mascot is the Indians. | Susan Pfannmuller, Special to the Star

Greaves lives in Kansas City but works in Olathe, just off Black Bob Road, which runs north-south from Strang Line Road at about 117th Street to 157th Terrace, where it becomes Lackman Road.

“When I first heard of it, I thought it was one word ‘blackbob’ and the name of some kind of plant or something,” he said in an email. “But when I saw the actual sign, it made me wonder, who was Black Bob, why is the road named that, and in these times, SHOULD it be named that?”

The simple answer is yes — unless you also consider honoring American Indian chiefs such as Tecumseh, Sitting Bull and Geronimo to be offensive.

Black Bob, who was half Miami and half Shawnee, led a band of Shawnee Indians inhabiting the Olathe area in the 19th century. The band, as well as a reservation that filled much of Johnson County, came to be named after Black Bob, so a street in his honor seems entirely logical.

“This issue arises from time to time that perhaps the name Black Bob Road has a racist connotation,” said Chief Ben Barnes of the Shawnee tribe. “That’s absolutely not the case.

“To actually name it after an individual, I don’t see a problem with that whatsoever.”

And, no, his name didn’t come from his skin color, but rather from his bobbed black hair.

Of course, none of this sugarcoats some elements of shame to the Black Bob story. As was the case with most American Indians, mistreatment by the white man was common. And with the Black Bob Band, it rose to the highest level of government.

What’s in a name

As the abovementioned pet hospital and batting cages indicate, there is disagreement about one word or two when it comes to Black Bob.

A popular landmark adds to the confusion. An island created in the 40-acre lake in Heritage Park, a Johnson County Parks and Recreation facility that opened in 1981, contains an old brick silo that reads “Blackbob Island.” The island didn’t exist until the park and lake were developed, so the name provides no historical evidence that one word might be correct.

Danneberg confirmed that “Black Bob” is accurate. He referred other historical aspects of the issue to Bob Courtney, a former administrator in the Olathe school district and a local historian.

Courtney couldn’t pin down when the road was named other than to say it existed before the Olathe school board debated using Black Bob for a new elementary school in 1978.

“I know the school board, before it decided on the name, had a real serious conversation about its appropriateness,” he said.

The conversation was perhaps not as serious when officials chose a school mascot. They settled on the fairly obvious “Indians,” which was common in 1978 but has come to be widely considered offensive for mascots and has been changed at schools around the nation, including at Shawnee Mission North High School, now home of the Bison.

Black Bob Elementary School continues to use Indians, although Becky Grubaugh, communications and media manager for Olathe Public Schools, said in an email that the school has adopted the sidekick “Thunderbird” and “does not use any imagery of Native Americans in current school spirit wear or school materials.”

When asked whether the school teaches students the story behind its name, she wrote:

“The school does not directly teach the history of Black Bob as it is not part of the district curriculum; however, there is a paragraph on Chief Black Bob hanging in the school hallway.”

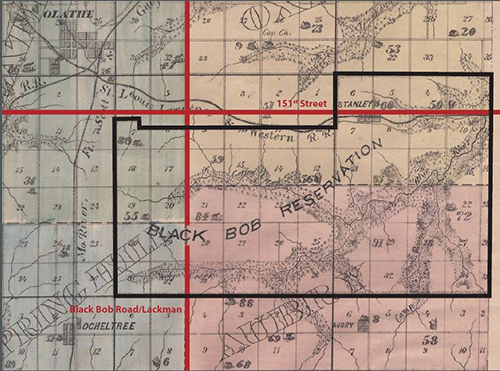

the Black Bob Band, with a modern street overlay indicating Black Bob Road in red. | Johnson County Museum

Not a short story

Rest assured, one paragraph can barely begin to tell the history of Black Bob. Here’s a condensed version from “History of Johnson County” (1915) by Ed Blair, the Johnson County Museum website and other sources, including The Star:

When the federal government removed the Shawnee from Missouri to eastern Kansas in 1825 under the Treaty of St. Louis, Black Bob and his Cape Girardeau Shawnee band refused to go, claiming they had been misled by the government, and settled instead in northern Arkansas.

Members of what came to be called the Black Bob Band even petitioned directly to President Andrew Jackson. They said that they had lived “peaceably” in “Upper Louisiana” for 40 years and that the Shawnee lands in Kansas had “a climate colder than we have been accustomed to, or wish to live in.”

That got them nowhere.

Eventually they relocated after an 1854 treaty gave them rights to 33,000 acres in what is now southeastern Johnson County, establishing the Black Bob Reservation. The Black Bob remained independent from the rest of Kansas’ Shawnee nation, however, and defied the Shawnee national council that was largely allied with the federal government.

Unlike most tribal organizations, the fewer than 200 members of the Black Bob believed in holding their lands in common rather than individual tracts. But the 1854 treaty had assigned the land in 200-acre allotments.

During the Civil War, the Black Bob were harassed and attacked by both Missouri bushwhackers and Kansas thieves, and they fled to Oklahoma Indian Territory. When they returned to their Kansas lands after the war, they found squatters inhabiting them and government agents illegally selling tracts.

That led to a nasty decades-long legal battle involving the Black Bob, the federal government and Johnson County officials. Some tribe members were tricked into selling rights to their land for almost nothing. The Star wrote, “One thirsty brave signed his over for a jug of whisky. Some got nothing at all.” Speculators would resell the land for $8-$12 an acre.

In 1870, a petition from “citizens of Johnson County, Kansas” to Congress suggested they deserved the Black Bob lands, claiming “the Indians are deriving no benefit from the sale of their lands, but squander the money they receive in drunken frolics, and are led to commit murder and other heinous crimes, and reduce themselves to vagabondage and ruin.”

The frenzy over land claims and titles among settlers led to the killings of at least two white men.

In 1895, a government special master issued a final settlement in the dispute that ordered settlers to pay $5-$10 an acre for land determined to be worth an average of $20 an acre.

Root of the issue

Chief Barnes of the Shawnee is more concerned with people learning about the past than in removing historical names.

“I think people don’t understand the local history of Kansas City (that) predates the city,” he said.

He doesn’t see any reason to change the names of places bearing tribal names, such as a call to remove the name of the Shawnee Indian Mission in Fairway. “That’s just crazy,” he said. “Why don’t we just start removing all the tribal names across the United States? … It doesn’t make any sense, it’s just silly.”

He identified real issues with naming places or businesses such as Squaw Creek, Big Chief and other offensive terms, including using Indians or Chiefs for team mascots. He was shocked to learn Black Bob Elementary School still uses Indians.

“But this name of Shawnee Mission or of Black Bob Road, these are not issues,” Barnes said, “They’re not issues. They’re real people. They’re not caricatures, they’re not cartoons. These are not fictional characters that somebody made up as a stereotype. These are real historical figures.”

Even businesses that use Black Bob in their titles don’t bother him because they are simply including the street name to help customers know their location.

However, he was irate when he learned of an Olathe city website page that describes historical street names. Citing Blair’s 1915 Johnson County book, the page says that Black Bob’s band, “being of limited intelligence … preferred to retain their tribal organizations and customs and to hold their lands in common, he wrote.”

“Oh, my gosh,” Barnes said. “Wow, that’s just crazy.”

Epilogue

- Chief Black Bob died in 1862 or 1864, according to several sources, which don’t cite his age.

- The Black Bob Band became known as Skipakákamithagî, meaning “blue water Indians” in the Shawnee language, because they lived on the Big Blue River.

- Olathe, a Shawnee word meaning “beautiful,” was founded in 1857, four years before Kansas became a state.

- The notorious William Quantrill and his Missouri bushwhackers attacked Olathe, known as a bastion of abolitionists, on Sept. 7, 1862, killing six men. Quantrill’s band also reportedly raided the Black Bob Reservation.

- Black Bob was the name of a border collie from Scotland in mid-20th-century British comics and fiction. Other Black Bobs: a Chicago blues pianist from the 1930s whose full name is believed to have been Bob Hudson, the nickname of 1970s professional boxer Bob Tuckett and the title of a song by Kid Rock.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.